During World War 2, Hamamatsu in Japan had been the location of many military plants so, even a year before the end of the war, had already become a target for repeated heavy air raids that left it in scorched ruins as far as the eye could see. Soichiro Honda had worked at the Tokai Seiki Heavy Industry plant until it had been turned into a heap of rubble. Production of aircraft, ships, and motor vehicles had stopped, and demand for the piston rings that had been his product had shrunk drastically, so he sold all his remaining stock to Toyota and took a year off to think about what he might do next.

There were rumours that he dabbled at building salt and Popsicle making machines till, in the summer of 1946, Soichiro called his younger brother Benjiro and several former employees of Tokai Seiki Heavy Industry to the remains of the company’s Yamashita Plant, where they used some construction materials they scrounged together to put up a small plant building among waving plumes of Pampas grass in a burned-out open plot at No.30 Yamashita-cho, Hamamatsu City. The barrack-like shed was erected to house an old belt-driven lathe, while outside, another ten machine tools stood in a row.

Hamamatsu had historically been the home of an active textile industry, so the first intention had been to manufacture a rotary weaving machine that Soichiro had conceived, but this seems to have failed due to lack of capital. They also attempted to manufacture frosted glass panes with floral patterns, then roofing sheets of woven bamboo set in mortar, and experimented with other ideas, but didn’t really come up with anything that seemed convincingly viable, so all these attempts were abandoned halfway through.

Things really began during late summer of 1946, in a moment of destiny, when Soichiro Honda saw a 50cc two-stroke Mikuni Shoko generator engine made for a No 6 wireless radio set from the former Imperial Japanese Army. He was immediately inspired by an idea to use it to power a bicycle.

This notion to motorise a bicycle by attaching an auxiliary engine was certainly nothing new and, indeed, dated back to the earliest origins of the motor cycle. While a few European motorised cycles had been imported to Japan in pre-war days, they remained quite infrequent, and post-war transport methods had largely reverted back to the bicycle, not only as a means of personal conveyance, but also piled high with loads for commercial use. Japanese society now centred on cycle transport, and Honda was convinced that an attachment engine could make good business.

Soichiro immediately set about developing a prototype with the engine mounted forward of the handlebars, where it drove the front wheel by a rubber roller pressed against the tyre, using a Japanese-style hot water bottle as a fuel tank. Handling of the machine however proved poor due to its high centre of gravity, while friction from the drive roller quickly wore down the poor-quality tyres of the time and caused frequent punctures, so the engine mounting was re-arranged to within the frame with a V-belt driving the rear wheel.

On 1st September 1946 a signboard was mounted across the entrance proclaiming the business as Honda Technical Research Institute, and the new company president and some dozen employees began work. The No 6 radio generator engine had been manufactured by Mikuni Shoko Company (more commonly known today for its carburettors), so Soichiro quickly went out to buy up the 500 remaining motors that were left at the Mikuni factories in Odawara and Kamata.

The first auxiliary bicycle engines went on sale in October 1946.

Honda A Type

It was obvious that the Mikuni motors would soon run out, so Honda began development towards making his own motor to succeed it. The Honda A Type two-stroke engine employed disc-valve induction with a belt clutching drive. At the direction of Soichiro Honda, engine castings became progressively produced from metal dies to replace the first sand-cast components, because he favoured the improved detail and reduced machining that resulted from die-casting. The high cost of bought-in die tooling would hardly have seemed viable against the model A’s relatively low production rate, so tooling expense was minimised by Honda fabricating his own dies rather than buying them in from toolmakers.

The A Type motorised cycle entered production in November 1947 and, in February 1948, Honda established a new engine assembly plant at Noguchi-cho. On September 24th 1948 the Honda Motor Co. Ltd was registered as an incorporated company, capitalised at 1 million Yen, and recorded a total of 34 employees (including its President, Soichiro Honda).

Honda B & C Type models were further cycle-based machines fitted with auxiliary engines but, in 1949, the company produced its first complete motor cycle using a fabricated pressed-steel channel frame and powered by a 98cc two-stroke engine. The channel frame design was a style that had been established in Europe since the 1920s and the Japanese Miyata Company had employed the same frame arrangement on a 175cc Asahi branded motor cycle as far back as 1933.

Soichiro said he was always talking of his dream that Honda would become a world-class manufacturer one day, and was quoted as having thought that somebody started calling the D Type his ‘Dream’, though the true details of how the name actually came about remain shrouded in the fog of time.

The bike however, generally proved to be a flop, since its two-speed semi-automatic gearbox design with a cone clutch needed constantly holding in first gear to maintain drive in the low ratio. The failure of the D Type also coincided with a difficult time for business as Japan slipped into an economic recession and the market for motor cycles began contracting.

More significantly, in October 1949, Takeo Fujisawa joined Honda as Managing Director. While Honda’s character presented a technical background, Fujisawa was more commercially orientated, and the two would be destined to fit together like lock and key—this was formation of the real Dream Team!

By early 1950, Honda’s business was going through a very difficult time, sales of the D Type were barely achieving over 150 units per month and stock inventories were growing, while working capital was shrinking. Accounts to suppliers were in arrears while wages to employees were being paid in late instalments and, for a time, it was looking as if Honda could go bust any day soon … then in June 1950, the Korean War broke out, and Honda received a large order for auxiliary engines out of the subsequent procurement boom.

Honda D Type (left) and E Type (right)

In response to the growing popularity of four-stroke engines, Honda presented its first OHV 146cc four-stroke motor cycle, the Dream E Type , which went on sale in October 1951.

Our episode starts in earnest in February 1952, when the total number of Honda employees was still only 214 and, despite the fact that Soichiro Honda despises smoky oil burning two-stroke engines (including his own two-stroke machines) that fume the crowded Japanese city streets, he returned to his original notion of auxiliary motors for bicycles.

The reason for this change of heart was that the two-stroke engine offered the simplest and most economically viable prospect for a small capacity motor, and the greatest potential for volume production.

Some aspects of the auxiliary engine concept conveniently fitted in with Honda’s ethos of ‘clean production’ in that small components would only require smaller and cheaper tooling than a large motor. The engine could be produced using as many die-cast components as possible, which would allow thinner and lighter castings offering finer detail and requiring less finishing processes.

Within the motor design, Honda applied some of his own ideas to try and improve combustion efficiency of the two-stroke engine.

Our featured Honda cyclemotor engine needed to be rebuilt in the workshops, so offered the rare opportunity to appreciate its internal workings. Few people in the western world will have had the good fortune to examine the inside of one of these engines.

The motor has a radial finned aluminium head and barrel with iron liner and twinned exhaust port, so isn’t expected to deliver efficient spent gas scavenging (by modern standards), but these were early days. Honda was obviously experimenting with his own two-stroke theory in this F Type engine, since the piston crown has a radial V-form on the top to try and channel transfer porting gas flow away from the outgoing discharge—an interesting idea, though several European manufacturers had already produced variations of the concept.

The engine is 40mm bore × 39.8mm stroke for 50cc, and rated as 1bhp @ 3,600rpm, with a given top speed of 35km/h (22mph).

The aluminium piston has three compression rings (which was a typical feature of Italian cyclemotors of the period). The single outlet port in the barrel is bridged by a ‘bar’ in the liner (Excelsior autocycle style), giving two wide though narrow exhaust vents from the cylinder. The shallow port heights of the transfers suggest that the motor is going to be developing power in its lower range, and most unlikely to achieve any of the high revs that would come to characterise Japanese two-strokes in later years. The overhung crank drives primary reduction by chain and sprockets in an internal oil bath case with a fibre cone clutch (a method carried over from the Model D) and secondary gear to an output shaft equipped with a cush-drive on the driving sprocket.

The magneto set is Mitsubishi (with its timing point clocked at 1mm BTDC) and a small generator coil to power a lighting set. We note that the Miyata cycle only has a headlight with no switch, so the lighting would appear to be permanently wired in! Notably, there is also no taillight and the cycle frame shows no witness of one ever being mounted anywhere, so perhaps the Japanese regulations of the time didn’t require a rear light?

The carburettor has a 10mm venturi and, though its make is unmarked, we think it might be an Amal licensed design. The F Type kit was supplied complete with a genuine Amal dual-lever control for shutter choke and throttle mounted on the right-hand bar, and Amal was certainly licensing carburettor designs to Japanese manufacturers into the 1960s.

Early model engines (like the one we have) seemed to take a horizontally mounted carburetter, while presumably later engines appear to have a different type of vertically arranged carburettor.

Manufacturing trials for the new F Type were completed in March 1952, but Honda’s real breakthrough came in the original and inspired way Takeo Fujisawa planned to sell the auxiliary bicycle engine kit by direct marketing. The Honda Cub F Type cyclemotor was probably the ideal that fitted perfectly to Fujisawa’s vision of a mass-market product. Its fresh-looking design, smart appearance, but cute appeal, made everyone feel that they would be happy using it.

Fujisawa recognised an untapped potential in the distribution network of 50,000 established bicycle shops that could be found all over Japan, and he planned to contact them all by the new concept of a direct marketing mail shot.

In 1952, there were no automated means of sending out 50,000 letters, and every single address had to be written out by hand. This work was initially put out to freelance clerks but, due to the time it was taking, all the staff had to join in as well, and later became further assisted by employees of the Mitsubishi Bank’s Kyobashi branch.

The first message might seem rather strange to western eyes, but this was a dramatically different culture, and these were very different times: ‘After the Russo–Japanese War (1904–05), your ancestors took the courageous decision to launch the imported bicycles in Japan, and they are still the basis of your business today. But now customers want bicycles with engines. We at Honda have made such an engine. Please reply if you are interested’—and he received 30,000 enthusiastic replies.

In a further effort to secure orders, Fujisawa had negotiated for the Kyobashi branch of Mitsubishi Bank to help by sending out a letter signed by the manager requesting customers to send their remittances to Honda through the Mitsubishi Bank’s Kyobashi branch, so the second stage of the campaign continued, ‘I am delighted to learn of your interest and we shall be distributing one machine per shop, on a first come first served basis. The retail price will be 25,000¥ and the wholesale price will be 19,000¥. Payment can be made by postal transfer or through the Kyobashi branch of Mitsubishi Bank’. The Japanese cycle trade was more generally used to ordering goods on consignment, and the idea of pre-payment probably came as a bit of a shock to them, but the product was intended to fit their needs perfectly—then everyone waited to see what would happen.

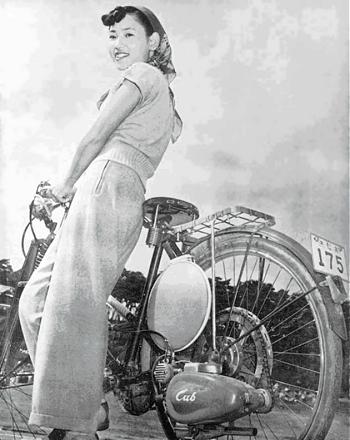

The response was incredible, with immediate replies from 5,000 shops, and the figure just kept on rising. Fujisawa succeeded in creating an independent sales network in almost no time at all, and the Cub F Type auxiliary bicycle attachment launched in June 1952, quickly to become known as ‘the red engine with the white tank’.

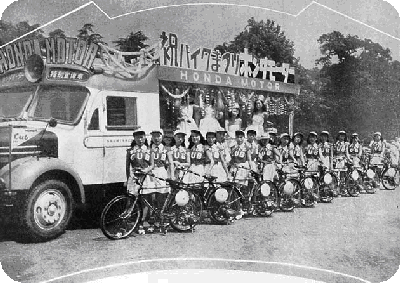

A demonstration of the Cub F Type that gained attention

at a Motor Cycle Festival in August 1952.

Honda Monthly (No.12) published the

same month said:

‘More than 150 promotion vehicles from Honda and other

manufacturers

paraded from Hibiya Park through the main streets of Nihonbashi,

Ueno,

Ikebukuro, Shinjuku, Shibuya, and Shiba in Tokyo in a major

demonstration to make motorbikes better known’.

Another promotion engaged the Nichigeki female dance troupe, then at the height of its popularity, to put on a splendid parade riding bikes fitted with the Cub F Type engine through the main street of Ginza, Tokyo. The route was lined with cheering spectators, so was reported all over the country, and the Cub F Type immediately became known as a bike that women as well as men could ride.

Fujisawa also used promotions for following up responses from the regional bicycle shops by engaging light aircraft for the company and using them to shower Honda’s promotional leaflets from the sky all over Japan—and of course, the leaflets always included names of the local outlets.

Fujisawa also put in place a unique consumer hire purchase system of payment by monthly instalments. Although the cost of a Cub F Type was only 25,000¥, that could still represent more than three months salary for the average white-collar worker. So Fujisawa thought up a revolutionary way of organizing loans. The way it worked was that if, for example, a customer wanted to pay in twelve instalments, they would sign twelve promissory notes, which were endorsed by the retailer and passed on to Honda. This proved to be a good system for both for the customer, and for Honda. It meant that Honda could be sure of getting paid and, if by any chance there was a problem, it only applied to a single purchase, thereby minimizing the risk.

So the Cub F Type scaled into mass production. It was a fantastic success, shipping 6,000 units in October and 9,000 in December, so the number of Honda’s employees correspondingly started to rapidly expand in order to keep pace with the increasing volumes. When the company was founded, the employees numbered only 34, and in February 1952 the total was still only 214. But by February 1953, it had grown more than 6-fold to 1,337. Honda’s production and sales grew so quickly that it very soon became the largest manufacturer of two-wheeled vehicles in Japan.

Miyata

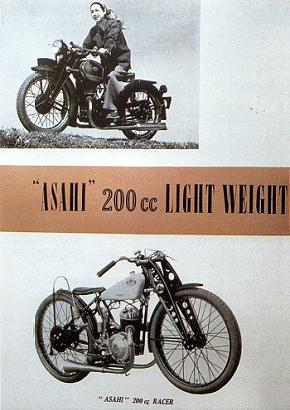

Miyata’s first Asahi motor cycles were copies of a British Triumph motor cycle. However, the one pictured below is a genuine Triumph.

The photo was taken after the 1925 Japanese TT: a 750km endurance race between Osaka and Tokyo. The name of the rider winning the race for the Kansai Autobi Club was … Miyata.

After the war, Miyata's interest in racing continued as this illustration from 1950 shows; as well as the normal road-going model. the ‘200cc Racer’ version was produced.

Our Honda F Type cyclemotor is mounted on a period Japanese Miyata bicycle with 20-inch frame numbered K759308 and fitted with 26 × 1 3/8 tyres. Its 32-spoke front wheel is calliper rod braked, while the 40-spoke rear has a back pedal hub.

The Miyata bicycle was the product of a long established business with an interesting history of its own, so we can use this timely opportunity for a briefly diverting moment of reflection…

The Miyata Company was founded by gunsmith and engineer Eisuke Miyata in 1881, when he established a factory and gun shop at Shiba, which he called Miyata Manufacturing, and began producing arms for the Imperial Japanese Navy.

In 1889, a visiting foreigner asked engineers at the Miyata gun makers to repair his bicycle; after this the business began to repair cycles as a sideline. In 1890, Eisuke’s son, Eitare, built the first prototype Miyata bicycle using rifle barrels from the family factory. Just two years later in 1892, Miyata bicycle manufacture received an unexpected boost by a request from Crown Prince Yoshihito (later to become Emperor Taisho), to build him a bicycle—that sort of thing could be very good for business back in those days.

Upon Eisuke’s death on 6 June 1900 and with the firearms market now being flooded by foreign gun manufacturers, Eitare converted the Miyata business entirely to bicycle manufacturing.

Miyata became one of the first mass-produced builders of motor cycles in Japan, which were sold under the brand of Asahi, and Miyata still continues to build bicycles today.

In a similar manner to the Japanese Meimon cycle we featured in our earlier Bridgestone cyclemotor article, this Miyata cycle is liberally covered with logos and graphics in both Japanese and English languages, though it’s fairly unlikely the cycles would ever have been exported to the north Americas or British international colonies—it’s inexplicably just what Japanese businesses did at the time.

Miyata’s logo comprised an ‘M’ within a gear wheel, and almost every component is marked in some way: front hub, Trade ‘M’ Mark; front mudguard embossed with ‘M’ logo & ‘M’ Japanese language decal, with two further embossed ‘M’ logo plates across the front mudguard stays; front brake calliper imprinted both sides Trade ‘M’ Mark; front fork crown cover plate imprinted with ‘M’ logo; handlebars imprinted, Trade ‘M’ Mark; frame headstock pinned with two enamelled badges ‘M’ logo Japanese language, and an English language decal ‘Electric Welded’; frame top tube decal ‘M’ logo with English language ‘Guaranteed Throughout, best material and workmanship’; frame down tube ‘M’ logo Trademark 16 gold medal decal; frame bottom bracket ‘patent no.358446/361183’ decal; frame seat tube ‘M’ logo ‘Miyata Works Ltd.’ & ‘KYT’ shield logo; both pedal arms imprinted Trade ‘M’ Mark, and ‘M’ logo moulded into rubber pedal blocks on each of all four sides; pedal chain guard ‘M’ logo 12 gold medal decal. Even the plates of the chain are stamped MYT! The leather saddle is imprinted both sides ‘Fully Guaranteed, Trade ‘M’ Mark, MYT saddle’, and pinned with a plate on the back Trade ‘M’ Mark. Rear mudguard embossed with ‘M’ logo, another ‘M’ logo plate across the top mudguard stay, ‘M’ logo Miyata Works decal, and MYT embossed into the mounting for the rear reflector—is that everything?

No, we missed the ‘M’ logos imprinted on the ends of the pedal bearing cover plates … ahh, and the ‘M’ logo pierced into the pedal chain wheel … surely that’s got to be the lot now? No, there’s even Miyata logos on the handle grips … and stamped on the head of the bolt for the saddle stay. We decide to call it a day with this game … that’s some serious branding obsession!

Our Honda F Type engine number is FE1-11863 (though we don’t have any useful references to decode quite what this serial may mean, but the number suggests it might date somewhere around September or October 1952).

The painted aluminium magneto cover is imprinted ‘Honda Cub’, and the engine mounting bracket cover stamped ‘Made in Japan’—notably in English language, even though the motor seemed to have been specifically produced only for the Japanese home market at the time it was made.

The F Type kit was supplied with engine unit, carburettor, exhaust, controls and cables, fuel tank, drive sprocket and chain. The drive sprocket carrier frame comes in halves so it can be threaded through the spokes, then held together by the sprocket (which also comes in two separate halves) when it is screwed to bosses in the carrier plate. There are four centring adjusters on the back of the carrier plate spokes to set concentricity, then the assembly clamps to the wheel spokes. The motor mounts off the left-rear of the frame, with further steadies from the cylinder head and to the rear stay.

The petrol tank clamps to the rear stay, and looks like a couple of frying pans welded together (some people also referred to it as a ‘bed warmer pan’), and has a spring-latching cap with internal splash plate. An ‘MC’ shield decal is presented in the middle face of the fuel tank, but we don’t know what this means.

The Honda engine has a neat little side stand mounted from a bracket bolted to its crankcase, the dainty stand leg being just six inches long, and it easily flicks down with your foot to prop the bike.

The left handlebar control also looks quite similar to an Amal dual-action decompresser–throttle cyclemotor control, but engages the decompresser by a short outward action of the thumb, and effects the clutch by a long inward action of the thumb. The natural default setting is with decompresser off and drive engaged, so you have to constantly hold the thumb trigger off to de-clutch. There is no latch to ‘lock’ this, so manoeuvring the bike needs the thumb trigger to be held in.

Probably an advantage of the cone clutch is that it offers a low operational drag for cycling, but you’d still be back-driving the final drive sprocket and chain set, output shaft, and secondary gear set to the clutch drum, so once the cyclemotor was fitted it probably wouldn’t have much practical use as a bicycle if the engine wouldn’t start. The drag in back-driving the transmission would make pedalling the cycle too sapping, so any motor breakdown would need the engine drive chain disconnected to re-enable the bicycle.

OK, we’ve arrived at the big moment—can we get it started?

Unscrew the fuel valve butterfly at the bottom of the tank, flick up the stand and mount up. While the clutch enables us to navigate the bike to the launch pad, we’re not sure whether this might be the best starting option? We have a choice of either backing the motor onto compression, pedalling up to speed and dropping the clutch, or pedalling away on decompress, then releasing the trigger. What the control doesn’t do is effect any transition between clutch and decompress, so it’s either one or the other.

Since there seems some motion resistance on the decompresser, we wonder if it might have primarily been intended as a means of stopping the motor, so we’re trying the flying clutch start first… Choke on, pedal up to speed, let off the thumb trigger—and the clutch just slips against the compression. OK then, that didn’t work…

We dismount to try to figure out what plan B may involve, and while pushing the bike back to the workshop we test how the engine turns over with the decompresser, which seems OK, then as soon as we release the decompresser trigger—the engine starts right up! Hold on Honda, we’re not aboard yet!

Quickly thumbing on the clutch before the bike takes off without us, we keep the motor running on the throttle lever and hop aboard. Cycling up and down the road while feeding in the clutch gives some idea of the general feel of the controls.

The motor runs with a lazy and mellow flat-burble … it’s very odd to think this really is a Honda, because it’s so far removed from any Honda that anyone would know.

Our pacer tracked a best of 23mph along the flat, and falling to 19mph on the light uphill section, but the motor pulled well under load and didn’t require any pedal assistance. Our best of 28mph in the downhill run was achieved in a crouch position, but the engine was well into its vibration zone at this speed, and clearly wasn’t comfortable.

Overhung crank engines very typically go into vibration once revs are pushed beyond their natural operating speed, which they can rarely maintain without the further aid of gravity since the speed is quickly lost as the vibration clips the power away as effectively as any rev limiter. There’s little point in increasing the power output of an overhung crank engine, since it just runs into the law of diminishing returns as the revs increase, so it’d just vibrate itself to death.

The Miyata cycle frame gave a hard and bumpy boneshaker ride due to the 26 × 1 3/8 cycle tyres offering little pneumatic effect, while both the cycle rod front brake and back-pedal coaster hub brake proved very poor, and certainly quite incapable of retarding our cyclemotor.

The old time Japanese cyclemotorists must have been pretty hardy folks to drive one of these for much distance on the roads of the early 1950s. We were glad enough to dismount after just a short test run … that’s about as much of that we need for now.

The Cub F (two-stroke, 50cc) clip-on motor became sold through some 15,000 independent bicycle shops across Japan, though was only manufactured for two years, but it did introduce the famous Honda ‘Cub’ trademark, which would become popularised over decades in various guises.

The little cyclemotor had firmly put Honda on the map, and carried the company through to the premier position of Japan’s motor cycling league. Production of the engine ceased in 1954, with Honda citing shifting consumer demand toward better products as Japan’s post-war economy improved, and associated quality problems with installations and components on other manufacturers’ bicycles, which Honda could have no control over.

The real masterpiece of the Cub F Type wasn’t so much in the cyclemotor engine as the way in which it was sold; that really gave Soichiro Honda the breakthrough he was looking for. While the motor was engineered to be manufactured under Honda’s new principles of mass production using die-casting processes to minimise finish-machining operations, it would have been a complete commercial disaster to mass-produce lots of cyclemotor engine kits without being able to sell them!

As much credit for the F Type’s success must surely be go to Honda business financier Takeo Fujisawa, who imagined the original means to mass market the sets. Honda’s breakthrough was not just in the ability to produce in volume, but also to sell in volume.

The cyclemotor’s story wasn’t quite over yet though, as Honda’s design and development department set to work on plans for more new products and, starting from around spring 1952, the company embarked on the development of two new models. One was the H Type, a general purpose engine based on the Cub F Type engine and developed at the request of agricultural equipment manufacturer, Kyoritsu Noki Co. The production of this started in September as an OEM product used to provide the power for back-mounted agricultural chemical sprayers, which provided Honda with a chance to enter the market for other motorised products. The general design and simple controls of the H Type sprayer unit took account of the need for it to be used easily by people with no experience of operating machinery. However, this joint venture soon came to an end and production of the H Type motor unit was concluded by a commercial decision from Fujisawa.