Cyril Kieft was born in Swansea in September 1911,

and followed his father’s footsteps working in the steel

industry. By 1935 he had risen to a position as joint

manager of the giant steelworks at Scunthorpe, but left the plant

at the end of that year and, with his father Alfred, purchased

two steelworks in Wolverhampton, and two others in

Shropshire. They were the Wolverhampton Steel and Iron

Company at Osier Bed Works, Horseley Fields; Monmore Green

Rolling Mills Limited, Cable Street; Haybridge Steel, Wellington,

Shropshire; and the Shropshire Iron and Steel Company

Limited.

Cyril Kieft was born in Swansea in September 1911,

and followed his father’s footsteps working in the steel

industry. By 1935 he had risen to a position as joint

manager of the giant steelworks at Scunthorpe, but left the plant

at the end of that year and, with his father Alfred, purchased

two steelworks in Wolverhampton, and two others in

Shropshire. They were the Wolverhampton Steel and Iron

Company at Osier Bed Works, Horseley Fields; Monmore Green

Rolling Mills Limited, Cable Street; Haybridge Steel, Wellington,

Shropshire; and the Shropshire Iron and Steel Company

Limited.

In 1939 Kieft purchased WG Birkinshaw &

Company Limited, drop forgers and edge tool makers at Reliance

Works in Derry Street, Wolverhampton. The company name was

changed to Cyril Kieft & Co.

Ltd. though products continued to be marketed under

Birkinshaw’s established ‘Pamax’ brand

name. The works produced forgings, including adzes, axles,

bars, forks, hammers, hatchets, hoes, mauls, picks, spades,

tongs, wedges and drop forgings for the Ford Motor Company.

The new business soon became the country’s largest

manufacturer of picks for coalmines.

In 1939 Kieft purchased WG Birkinshaw &

Company Limited, drop forgers and edge tool makers at Reliance

Works in Derry Street, Wolverhampton. The company name was

changed to Cyril Kieft & Co.

Ltd. though products continued to be marketed under

Birkinshaw’s established ‘Pamax’ brand

name. The works produced forgings, including adzes, axles,

bars, forks, hammers, hatchets, hoes, mauls, picks, spades,

tongs, wedges and drop forgings for the Ford Motor Company.

The new business soon became the country’s largest

manufacturer of picks for coalmines.

In 1941 Cyril purchased Sellman & Hill Limited of Stewart Street, Wolverhampton, manufacturers of the ‘Crescent’ brand of aluminium hollowware. During the Second World War he trained as a bomb disposal officer in the Home Guard.

In 1946 the four main steelworks were combined under the name of the Wolverhampton Iron & Steel Company (1946) limited, with Cyril as Managing Director, but fearing the prospect of being made a civil servant as elements of the industry were being nationalised, he sold his interest in the company before the end of the year.

After the sale of Wolverhampton

Iron & Steel Company (1946) Ltd,

Cyril purchased an ex-MoD munitions factory at Bridgend,

South Wales and closed the Stewart Street works, moving

production of the hollowware to Bridgend. The Bridgend

works initially undertook general presswork, then added

thermostats, electric kettles, jelly moulds, Tilley lamps, hooks,

components for the motor industry, and locks of their own design

to the product range. The venture was very successful,

employing about 450 people. Cyril also purchased Orton and

Smith Limited of Stringes Lane, Willenhall, who specialised in

the manufacture of meat cleavers.

After the sale of Wolverhampton

Iron & Steel Company (1946) Ltd,

Cyril purchased an ex-MoD munitions factory at Bridgend,

South Wales and closed the Stewart Street works, moving

production of the hollowware to Bridgend. The Bridgend

works initially undertook general presswork, then added

thermostats, electric kettles, jelly moulds, Tilley lamps, hooks,

components for the motor industry, and locks of their own design

to the product range. The venture was very successful,

employing about 450 people. Cyril also purchased Orton and

Smith Limited of Stringes Lane, Willenhall, who specialised in

the manufacture of meat cleavers.

Cyril’s hobbies at this time included collecting stamps, Welsh china, and motor sport. His interest in racing cars probably grew from listening to his father’s stories about the great races at the Brooklands circuit, where Alfred had been a frequent visitor.

Cyril also developed interests in sports cars, becoming involved with the new Formula-3 racing category from its inception in 1948. F3 initially was established as a ‘hobby’ class for maximum thrills at minimum cost, based upon rear engined cars with chain transmission using 500cc single-cylinder motor cycle engines from JAP, Norton, Rudge and Vincent.

In 1949 Cyril purchased a 500cc Marwyn racing car to unsuccessfully compete at the Lydstep hill climb. Being disappointed with the capability of this vehicle, he resolved to build a better machine of his own design but, after a previous competitor had rolled his car, Cyril also appreciated the dangers of such competition and that actual race participation was probably not for him. Instead he decided to concentrate on design and team management, and from 1950 handed his cars over to other professional drivers.

Kieft started Formula-3 motor racing by buying the Marwyn F3 car designs after the former company failed, and used the designs as a base for his own 500cc car. Several Kieft F3 sports cars were sold to privateers and some competition success resulted. Publicity was gained by successful attempts on a series of records at the Autodrome de Linas–Montlhéry in France, with one of these drivers being a young Stirling Moss, who explained the shortcomings of the cars and helped in their further development, as a result of which a new design was produced. Moss and his manager Ken Gregory became directors, while the company moved to new premises at Reliance Works in Derry Street, Wolverhampton.

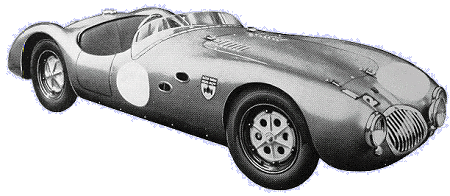

Kieft 1,100cc Sportscar

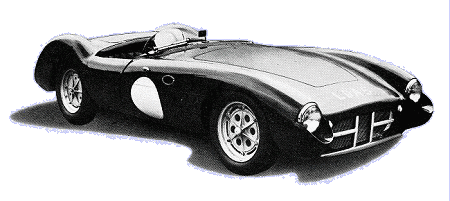

Re-styled model of Baxter Birmingham-built Kieft

1,100cc Sportscar.

A new design by Gordon Bedson, who had joined the company from the aircraft industry, was produced in time for the 1951 Whit Monday Meeting at Goodwood where it won the Formula Three event driven by Moss.

In September 1952, Kieft’s Bridgend factory closed due to production difficulties caused by an intermittent electricity supply following the strikes in the South Wales coalmines. Cyril announced that he was now intending to build a two litre sports racing car, and all production moved to Derry Street to deploy the skills of the proven Wolverhampton workforce.

Don Parker was employed as works driver and won the British Formula Three championships in 1952 and 1953.

F3 motor sport really peaked over 1952–53 when Kieft cars with Stirling Moss and Don Parker at the wheel won many races and became a leading challenge to Cooper’s domination of the class.

In 1954 Kieft started to make a two-seater sports car, which could also be used as a road car. Using a Coventry Climax FWA 1098cc ohc engine, all independent suspension using transverse leaf springs at the rear and a lightweight glass fibre body. The car was really a racing car, and at £1,560 it is doubtful if any were actually bought for use as road cars.

By 1954 Kieft had also produced a model 2-litre car for Formula-2 and was working on two other chassis for Formula-1 designed under the direction of Walter Hassan, to employ Coventry Climax 4.5-litre Godiva V8 motors, but after several months of waiting, the engines had still not been delivered and Cyril was beginning to lose heart. When the F1 prototypes were finally completed for test, they failed to achieve the expected performance, and the project was cancelled. While 35 Formula-3 cars had been built, this whole motor sport business was costing a lot of money and, at the end of 1954, Kieft sold the company to racing driver Berwyn Baxter of the Baxter Screw and Rivet Company, Birmingham, who took over all of the cars in production, leaving Cyril free to move his focus towards fresh projects—now involving two-wheel machines!

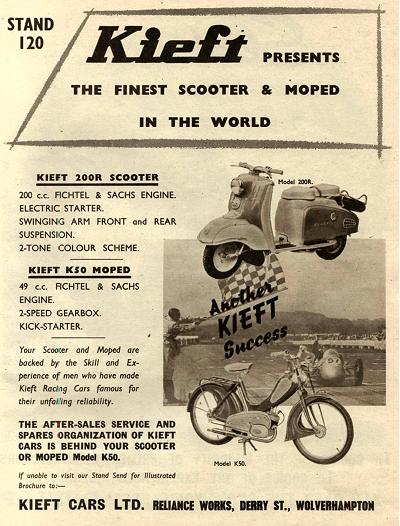

The new plan was to establish a licence with the

German Hercules Company to import and distribute its moped and

R200 scooter models under a Kieft badge, since the British

Hercules Cycle and Motor Co. already retained rights for use of

Hercules branding in the UK. Both the scooter and moped

employed Fichtel & Sachs engines, and both machines came with

their own particular marketing difficulties…

The new plan was to establish a licence with the

German Hercules Company to import and distribute its moped and

R200 scooter models under a Kieft badge, since the British

Hercules Cycle and Motor Co. already retained rights for use of

Hercules branding in the UK. Both the scooter and moped

employed Fichtel & Sachs engines, and both machines came with

their own particular marketing difficulties…

The R200 scooter was an ‘up-market’ model that came with four-speed gears, 12V Siba electric dynastarting, and a high price tag of £217 including purchase tax (when a kick-start Lambretta 150 came for just £154). Also the German Hercules Company had developed its scooter in conjunction with the German Triumph Werke Nürmberg Company, which was also going to be selling the same version of the scooter into the UK as the TWN Contessa, so with all factors taken into account, there wasn’t going to be much margin for profit on the scooter.

The K200 scooter was branded with a Kieft enamel badge with a Welsh dragon logo as proudly worn by the Formula-3 racing team … but the R200 was only an introductory Plan-A to establish the Kieft name in the market place. Plan-B was quickly to replace the imported R200 with his own British-built Kieft scooter.

Kieft Cars Ltd, Reliance Works, Derry Street, Wolverhampton first presented their now titled 200R scooter and K50 moped models in motor cycling press announcements from October 1955 before the Earls Court Motor Cycle Show in November 1955, where the new machines were set to appear on stand 120.

Initially released pictures of the Kieft K50 illustrated it as a Hercules 215 model having rigid cycle-type forks with a torsion pivot below the steering head to provide some degree of springing effect.

The Earls Court Motor Cycle Shows had established a reputation for throwing up surprises, and the BSA stand presented Cyril with some considerable concerns, as BSA showed their new prototype Beeza scooter. The prospect of this large motor cycle company with its extensive dealer network building a competitive scooter was enough to put his own idea of an all-British scooter plan straight onto hold.

Prototype test and show models of the Kieft K50 moped were all based on the Hercules 1955 model 215 moped, but by the time Kieft K50 mopeds were being delivered for market, the actual moped being sold had already become the Hercules 1956 model 216 moped with pressed-steel front forks and torsion rubber suspension metalastic bushes at the front axle.

Our Kieft K50 is a

Hercules 216 model, which still carries its original serial and

was registered on 25/10/1955, even before the Earls Court

Show! This probably illustrates that no Kieft model 215

mopeds ever actually were sold.

Our Kieft K50 is a

Hercules 216 model, which still carries its original serial and

was registered on 25/10/1955, even before the Earls Court

Show! This probably illustrates that no Kieft model 215

mopeds ever actually were sold.

Frame number 148154 seems to suggest that the chassis serial numbers were factory stamped on the frames in Germany, and that Kieft never applied its own serialisation sequence.

All main features of the bike are as imported: Magmeg alloy rims, Magura controls, Denfeld rubber-sprung saddle, and Hella headlamp.

The rear number plate and Wipac lamp are expected British market additions since continental rear lamps didn’t come with a clear port to illuminate the rear number plate as required by UK law, so wouldn’t have been compliant.

The enamel Kieft badge used on the scooter was too large to be fitted on the moped, so the ‘Hercules’ script badges on the petrol tank and rear mudguard were replaced by ‘Kieft’ script, and the small plastic diamond ‘H’ badges on the side panels replaced by small plastic ‘K’ badges.

The German Hercules Company was also partial to fitting a cast alloy badge atop the front mudguard, which Kieft simply replaced with a ‘pedestrian slicer’ front number plate as demanded by UK law for motor cycles up until the later 1970s.

Time to take our moped out for a spin…

Fuel tap

off–on–reserve at bottom right of tank, just above

the cylinder head. These old Bing carburetters have no

choke, so the only way to enrich for starting is by flooding the

float chamber using the tickler. Since the side panels

cover access to the carburetter, there’s a tickler

extension peeping above the left-hand side, so press to work the

button by remote control … except that you can’t see

when the carburetter starts to flood—until it dribbles all

over the floor underneath the motor. You can hardly imagine

that being acceptable today, but these were very different

times.

Fuel tap

off–on–reserve at bottom right of tank, just above

the cylinder head. These old Bing carburetters have no

choke, so the only way to enrich for starting is by flooding the

float chamber using the tickler. Since the side panels

cover access to the carburetter, there’s a tickler

extension peeping above the left-hand side, so press to work the

button by remote control … except that you can’t see

when the carburetter starts to flood—until it dribbles all

over the floor underneath the motor. You can hardly imagine

that being acceptable today, but these were very different

times.

In neutral, push down on a pedal to spin the motor, but it doesn’t go. We try several times, but it still won’t start … perhaps we shouldn’t have flooded it, so we spin the motor over a couple more times with the throttle wide open, and our Sachs engine coughs into life with a cloud of blue smoke from the tailpipe.

We buzz the motor in neutral to clear the tubes, and then pull in the clutch lever, which allows the twist-change to be turned forward for first. The change engages with a bit of a clunk, which at least tells us we’ve found the gear, wind on the throttle while letting out the clutch, and K50 seems to pull away surprisingly easily for such an old low-power motor … but the gear appears to run out fairly quickly and finds us soon reaching for second. Clutch in again and twist back 90º though neutral into second (top). Dropping the clutch again reveals that the gears are lightly spaced so there’s no big jump to second as a number of other motor makes exhibit. Our Kieft feels to be delivering quite good torque as it still pulls well enough to climb up its range with relatively little effort.

At this stage its hard to assess the actual speed since our mount isn’t equipped with a speedometer, but this doesn’t feel to be particularly quick so we’re already getting the impression our Kieft is quite low-geared (not untypical of many low-powered mid-1950s’ machines). Tracked by our pace vehicle, we press on to build heat into the motor since old cast-iron barrel engines often don’t give their best until they get hot.

Comparing notes with

our pacer, cruising on flat settled down around 25mph, at which the motor was buzzing

fairly. Above 25 everything tended to go smooth and felt as

if this might be a little beyond the happy zone.

Comparing notes with

our pacer, cruising on flat settled down around 25mph, at which the motor was buzzing

fairly. Above 25 everything tended to go smooth and felt as

if this might be a little beyond the happy zone.

Best on flat in still air topped out around 28mph, and we could just about scrape 29 by dipping into a crouch. A tailwind would probably take the bike beyond 30, but we couldn’t even find a breath of breeze today.

The downhill run clocked a maximum of 34mph, at which a broken exhaust note of four-stroking sounded as if the spent gas clearance was getting all in a tizzy and holding back the prospect of further revs, so that was the ceiling.

The brakes worked satisfactorily within the limits of the bike, the back-pedal rear brake being particularly good.

The front metalastics seem to contribute little toward any suspension effect, and despite cornering confidently while following a line through smooth bends, we felt the lack of effective suspension would probably cause this light machine to bounce under bumpy conditions.

The headlight provided a dull yellow glow, which was about normal for any 1950s’ motor cycle.

Feeling that our Kieft might have been running a little under-geared, back at base we set about checking the drive ratio, and finding a 12-tooth (standard) front sprocket, we wondered how it might compare with a 13-tooth? No problem, since the workshops had a 13 in stock, and after a flurry of spanner work the following day, we’re ready to go again!

Acceleration from a rest was still strong and capable, so first gear didn’t seem at all compromised by the change. Switching into s econd also found our mount still pulling enthusiastically once the gear was dropped in, and the pace vehicle reported our cruising on flat now at 30mph in upright position with a fair tailwind.

Cranking on the throttle now found a best on flat of 35mph available by adopting a crouch position and assisted by a tailwind, but turning into the wind further up the course noticeably showed against the motor’s low 1¼bhp output as the bike now laboured hard to struggle up to 25 on the flat. Despite tucking into a crouch, our downhill run against a headwind blowing strongly up the slope failed to clear the 35mph barrier, but given more favourable conditions should certainly best that target.

The standard 12-tooth gearing felt a little low in top, making the motor seem rather too buzzy. The 13-tooth ratio felt rather better under favourable conditions, but something of a labour when conditions turned against the low output engine. Inclines and riding against headwinds in top had now become harder work.

Ratio

selection could be a subjective decision according to the weight

of rider and general terrain around where you live. With

the flat landscape of East Anglia, higher drive ratios are

generally preferred by riders for faster cruising, better

economy, and more leisurely revs, but heavier riders in a more

hilly area might well favour retaining the standard 12-tooth

sprocket.

Ratio

selection could be a subjective decision according to the weight

of rider and general terrain around where you live. With

the flat landscape of East Anglia, higher drive ratios are

generally preferred by riders for faster cruising, better

economy, and more leisurely revs, but heavier riders in a more

hilly area might well favour retaining the standard 12-tooth

sprocket.

By the mid-1950s, demand for coal picks, the company’s main product at Derry Street, had greatly reduced due to mechanisation of the coal industry. Cyril decided to concentrate on the manufacture of tungsten carbon cutting heads for coal cutters, and acquired two drop forging machines for this purpose. After installation, the neighbouring businesses and residents complained about the noise, and eventually he was forced to close the works. To keep production going he purchased the Drop Forging Company at Witton, Birmingham and moved production there in 1956.

Kieft Cars left Wolverhampton in 1956 as Berwyn Baxter moved the business to nearby Birmingham where it now mainly concentrated on the preparation and tuning of other makes of cars, though a restyled model of the Kieft 1100 Sports car was also produced.

As 1956 wore on it became apparent that BSA’s Beeza scooter project was a non-starter, so Cyril’s Plan-B to produce his own all-British scooter was back on again. The first phase of this project involved the installation and testing of Villiers engines in the Hercules R200 scooter body shell.

A Mr Tipper with young lady-friend passenger rode one of these test-bed machines on a 6,000 mile European two-month road trip toward the end of 1956. The installation was satisfactorily proven and everything reportedly went fine, so new Kieft model scooters built from the Hercules body shell but fitted with 200cc and 150cc Villiers engines, appeared in trade listings for a few months.

The Kieft 150cc Villiers scooter was listed £57 cheaper than the 200R Sachs scooter, and would have been competitively priced against imported Italian Lambrettas and Vespas—however the Hercules/Villiers/Kiefts never went into production.

Cyril Kieft was already engaged in Plan-C, and discussions with Willenhall Motor Radiators of Wolverhampton were leading to the final designs of a new all-British scooter.

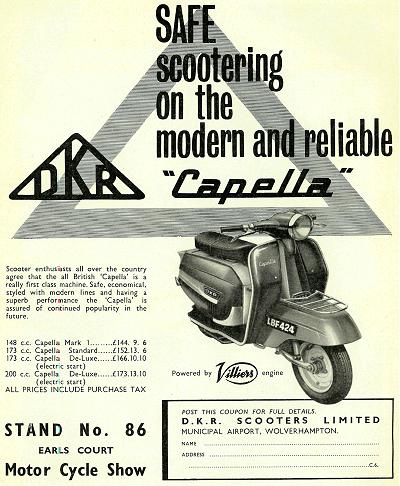

The DKR Company was established in 1957, taking its title from the initials of Messrs. Day & Robinson of Willenhall Radiators, and Cyril Kieft.

For the 1957 season, the German Hercules Company introduced a new model 217 moped with rear suspension, which Kieft adopted as a K50 De-Luxe model at £85. Kieft, however, had not secured sole licence on this De-Luxe machine, and it was also being sold into the UK market by Triumph Werke Nürmberg as the TWN Fips at a similar price.

The German Hercules

Company was also selling into some European markets under the

‘Prior’ badge (a branding it had adopted for

occasional export use from as far back as 1904). The German

Hercules business relationship with Kieft pretty much fell apart

at introduction of the first DKR Dove scooter listed

for UK market sale in July

1957. The R200 scooter and 217 moped models continued to be

sold into Britain under the Prior brand name by BP Scooters Ltd.,

No.10 Buildings, The Airport, Wolverhampton as BP Scooters took

over distribution of German Hercules products in September

1957.

The German Hercules

Company was also selling into some European markets under the

‘Prior’ badge (a branding it had adopted for

occasional export use from as far back as 1904). The German

Hercules business relationship with Kieft pretty much fell apart

at introduction of the first DKR Dove scooter listed

for UK market sale in July

1957. The R200 scooter and 217 moped models continued to be

sold into Britain under the Prior brand name by BP Scooters Ltd.,

No.10 Buildings, The Airport, Wolverhampton as BP Scooters took

over distribution of German Hercules products in September

1957.

The DKR Dove scooter with fan-cooled 148cc Villiers 30C three-speed engine was joined in 1958 by a new DKR Pegasus scooter with 148cc Villiers 31C electric-starting three-speed engine, and Defiant scooter with 197cc Villiers 9E electric-starting four-speed engine, all models employing the same frame and body shell.

1959 brought a new DKR Manx scooter with 250cc Villiers 2T twin-cylinder engine and 70mph capability, though the same brakes.

The end of the 1959 season presented a revised Dove II scooter employing a kick-start version of the Villiers 31C engine to replace the original Dove model and, early in 1960 a Pegasus II with 174cc Villiers 2L engine.

A new ‘modern-look’ Capella body shell style was introduced for 1961 to replace all the Dove and Pegasus models with a 148cc Villiers 31C Capella, 174cc Villiers 2L four-speed kick-start Capella Standard, and 174cc Villiers 2L four-speed electric starting Capella De Luxe. The Defiant and Manx models were dropped in September, for replacement in 1962 by a Capella 200 De Luxe with electric-starting 197cc Villiers 9E engine, followed by a Capella 200 Standard version for 1963.

DKR continued with these five models until production ceased early in 1966 when sales had been undercut by cheaper foreign scooter imports.

The Kieft Motorsports Company was sold again in 1960 and changed its name to Burmans.

The name of Kieft Sports Car Co. Ltd. is now owned by Canadian Peter Schömer and based in Chichester, West Sussex, near Goodwood.

In semi-retirement Cyril Kieft enjoyed sailing both at home and in the Mediterranean in his motor cruisers. He was a member of the Royal Yacht Club, and very much a family man. In 2002 he moved to Spain to live near his family, but sadly died on 10th May 2004.