Since we’ll be

picking this particular story up from the earliest days of

Phillips cyclemotor bicycle frames, it’s worth mentioning

that there had now become two Phillips companies, both registered

from the same address of Credenda Works, Smethwick,

Birmingham.

Since we’ll be

picking this particular story up from the earliest days of

Phillips cyclemotor bicycle frames, it’s worth mentioning

that there had now become two Phillips companies, both registered

from the same address of Credenda Works, Smethwick,

Birmingham.

JA Phillips & Co. Ltd. was the original company who manufactured all the cycle—related components, and Phillips Cycles Ltd. who assembled and sold all the bicycles.

At the advent of cyclemotoring in Britain by the close of the 1940s, the first pioneering attachment engines were simply being fitted onto standard bicycles—but with the number of frame and fork related failures, it quickly became apparent that a more robust and suitable ‘special cycle’ would be required for motorised applications.

During the 1950s, several cycle makers produced special reinforced frames for mounting cyclemotor engines. Among them were BSA (including New Hudson and Sunbeam variants), Elswick, Mercury, Phillips, Triumph and Sun.

These could be supplied as a complete cycle for most applications, or without the rear wheel if a Cyclemaster motor wheel was intended to be installed.

Common features of these special cyclemotor cycles invariably included:

A strengthened frame, often with a ‘dropped-tube’ arrangement for a lowered saddle position to give more comfortable powered riding, but less suited for pedalling; though a lesser issue in this application as pedals would generally only be used for starting the machine and occasionally assisting on hills.

No rear brake was fitted for Cyclemaster models (braking being integral in the hub on the 32cc version), and on other models rear braking often comprised a coaster hub option.

A braced or sprung front fork.

Heavier grade ‘Carrier’ 26×2×1¾ wheels for a more comfortable ride, and optionally to include hub braking.

Fitment of heavy-duty carrier mudguards for extra protection, and these being more resilient for the mounting of number plates.

A lighting set designed to run from the engine magneto-flywheel generator.

A lower-than-usual pedalling ratio to aid starting and assistance on hills.

Other variations included optional Gents’ ‘diamond’ or Ladies’ style ‘open’ frames, and offering a wide selling choice of special features.

Phillips produced a range of these special ladies’ and gents’ styled motorised cycle frames, with options of drum or rim brakes for the front wheel.

In these promising days of

the cyclemotoring boom, it would have been a logical

consideration for bicycle companies to be looking at the business

prospects of progressing into motorised cycle frames, and it may

be considered that Phillips’s first cyclemotors might have

comprised the special frames they built for the express purpose

of mounting particular cyclemotor engines, like the Cyclemaster

and Firefly. The different cyclemotors of the period

however, tend to be more commonly identified by their engines

than the make of their frames, so technically the first Phillips

cyclemotor was probably their P36X Motorised Cycle—except

that it didn’t exactly originate from Phillips … The

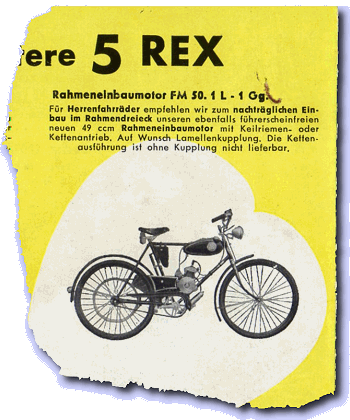

engine is a Rex FM50, and Rex was the original source for the

design and general arrangement of the machine.

In these promising days of

the cyclemotoring boom, it would have been a logical

consideration for bicycle companies to be looking at the business

prospects of progressing into motorised cycle frames, and it may

be considered that Phillips’s first cyclemotors might have

comprised the special frames they built for the express purpose

of mounting particular cyclemotor engines, like the Cyclemaster

and Firefly. The different cyclemotors of the period

however, tend to be more commonly identified by their engines

than the make of their frames, so technically the first Phillips

cyclemotor was probably their P36X Motorised Cycle—except

that it didn’t exactly originate from Phillips … The

engine is a Rex FM50, and Rex was the original source for the

design and general arrangement of the machine.

As well as selling other types of engine sets as front or rear mounted cyclemotor attachment kits, the German Rex Company also sold their original version of the Motorised Cycle widely across the continent as both attachment kits, and as a complete machine … except in Britain where Phillips contracted an exclusive import and distribution licence under their own brand.

Phillips introduced its P36X from October 1954, just

ahead of the Earls Court Show of that year, though somewhat late

in the day of the cyclemotor boom, as there was already a number

of competing machines well established in the market.

Phillips introduced its P36X from October 1954, just

ahead of the Earls Court Show of that year, though somewhat late

in the day of the cyclemotor boom, as there was already a number

of competing machines well established in the market.

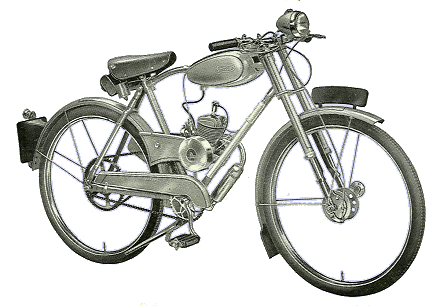

Lined up against its period cyclemotoring contemporaries with their DIY bolt-on and bitty image, the Phillips Motorised Cycle would probably have presented as a really slick cyclemotor of its time. Today it wears an old fashioned air, but carries that look of dainty and delicate elegance. Viewed from several angles there’s some very traditional and classic style about this machine.

Managing to evade the oppressive appearance of industrial brutality, the braced forks look elegant yet purposeful, though the addition of reinforcing struts offers no actual benefit of suspension. The idea behind this adaptation was that bolting on a cyclemotor engine would increase the vehicle weight, and generally push the machine along at a faster pace than typical cycling. Under such stresses, standard bicycles could experience broken forks and frames, so a special class of heavy-duty cycles became developed specifically for cyclemotoring applications.

The Rex FM50 kit comprised the engine, rated 1bhp @ 3,800rpm, with mountings, drive chain guards, tensioner and rear sprocket set, 12mm Pallas carburettor, exhaust, fuel tank, tap and cap, latching clutch lever and throttle control. Even all the original Rex illustrations were adapted into the Phillips Motorised Cycle handbook!

Phillips assembled the Rex-supplied components to their own 22-inch drop-tube frame, topped with a Wrights S.65/3 tension-sprung saddle. The frame rolls on a chrome plated British Hub Co. front hub with balancer flange laced into Dunlop Westwood pattern rim with 26×2×1¾ carrier tyre, while the rear has a Perry Coaster hub with back-pedal bronze cone hub brake and laced to matching rim and tyre.

Many

cyclemotors just seem to have their engines hung in all the

‘wrong’ places about the bike! Unbalanced over

the front wheel, unbalanced over the rear wheel, overhung behind

the rear wheel, bolted off one side of the rear wheel, squeezed

in between the pedals’ arc beneath the bottom bracket,

inside the front wheel, inside the rear wheel—just

everywhere it seems, except the conventional place within the

frame!

Many

cyclemotors just seem to have their engines hung in all the

‘wrong’ places about the bike! Unbalanced over

the front wheel, unbalanced over the rear wheel, overhung behind

the rear wheel, bolted off one side of the rear wheel, squeezed

in between the pedals’ arc beneath the bottom bracket,

inside the front wheel, inside the rear wheel—just

everywhere it seems, except the conventional place within the

frame!

The P36X is one of those very few cyclemotors with its lightweight, all-alloy Rex engine mounted in pretty much the right place within the frame, and delivers its transmission by a proper chain drive instead of rollers on tyres, or old fashioned rubber belt.

If you were looking for a cyclemotor you could relate to like a conventional motor cycle—then the Phillips Motorised Cycle was pretty much the only one!

Our featured bike appears to be a nice early example, showing frame number T119695 & engine number 350078, with its original registration serial dating the machine to around the end of 1954.

Turning on the fuel tap and following the prescribed starting procedure ‘An ingenious cold-starting device comprises a self-cancelling air-strangler plunger on the carburetter; opening of the twistgrip throttle control automatically returns the plunger to its neutral position’.

Yeah, right!

Well, after pedalling the wretched thing up and down

the road lots of times, and reducing ourselves to a quivering

puddle of jelly slumped on the verge, we came to the conclusion

that the old-time marketing blurb was no more representative than

all the modern commercial spin that we’re bombarded with

today.

Well, after pedalling the wretched thing up and down

the road lots of times, and reducing ourselves to a quivering

puddle of jelly slumped on the verge, we came to the conclusion

that the old-time marketing blurb was no more representative than

all the modern commercial spin that we’re bombarded with

today.

Basically, and in summary, this ‘simple easy-starting device’ doesn’t seem to work at all.

Looking more closely at the Pallas carburettor, there appears to be a small tickler pin coming from the top of the float chamber, which might even seem as if it was put there as a very simple, yet traditional, tried-and-tested back-up device for when the latest development in ‘ingenious cold-starting technology’ may not function under the challenging conditions of a pleasant spring afternoon in one of the mildest European climates … so we hold down the tickler pin till the carburettor overflows profusely. Well, that’s sure flooded now, and what do you know—yes, it finally starts!

There was still some reluctance from the engine in the early spluttering phase, which could only be satisfied by further copious administrations of the primitive fuel flooding back-up device.

‘Would you care to try a little bit of the ingenious modern cold-starting technology now?’

‘No thank you, I’m going to stop again if you try using that thing on me.’

‘Well maybe another bucketful of fuel by the traditional method then?’

‘Oh yes please, that’ll do nicely.’

So

this saga went on, until the engine worked up enough heat to

start gently frying an egg, then we seemed to be ready to go!

So

this saga went on, until the engine worked up enough heat to

start gently frying an egg, then we seemed to be ready to go!

There’s only a single speed gear with a manual grip-lock clutch, and a low-power motor that we now really don’t want to risk stalling out, so pedalling away and gingerly feeding in the clutch while piling on the revs assures a stall-free getaway. Heading down the road confirms our suspicions that there’s no surplus of power here, while opening the throttle involves the creation of more noise, there’s also a period of patiently waiting for the motor to catch up with what you’ve asked it to do. This is rather like the throttle-lag you used to get on the old Saab Turbo saloons—but much slower.

Once the engine has run enough to get itself properly hot, the bike finally settles down to contentedly burbling along in the low 20s, but to get much more along the flat requires favourable conditions (not any headwind, preferably some tailwind).

Best on flat paced to maximum 25mph. Sitting upright or in a crouch, 25 was the peak at which motor revs became limited by four-stroking from the restricted exhaust porting failing to clear spent gasses. Though imperceptible on our pacer’s speedometer the downhill run seemed slightly faster, as this just about managed to get the petrol tank vibrating on the frame, which we never achieved at any other point along the flat—so we’d probably claim a pinnacle of maybe 26mph?

Any uphill climbs were spoilt by a slightly slipping clutch requiring the throttle to be eased back, and demanding some pedal assistance, since the clutch was unable to sustain constant drive against gradients. This is an all-too-common complaint about these Rex single-speed dry clutches, which were added-on as a feebly engineered afterthought, and consistently let their bikes down. The clutch lever at the handlebar operates with a two-position latch, the first latch position being adjusted for motorised riding operation, and the second latch position engaged to reduce drag when it might be required to cycle the machine with the pedalling gear like a normal bicycle.

The

same clutch issues would subsequently be carried over to the

later Phillips Panda mopeds, which only operated a single stage

latch for their Amal clutch lever, and further compounded the

problems.

The

same clutch issues would subsequently be carried over to the

later Phillips Panda mopeds, which only operated a single stage

latch for their Amal clutch lever, and further compounded the

problems.

The ‘brakes’ were practically non-existent! The same Perry Coaster back-pedal rear brakes have been much criticised in the past as being completely ineffective on the later Phillips Panda Mk 1 & Mk 2 models with 23-inch wheels. The same brake on a larger 26-inch wheeled bike is just another 12% more useless than utterly hopeless! Even if you stand on the back pedal with all your weight, there’s still hardly any effect.

The front brake seems to function OK when you’re navigating the bike around the garage, but has no retarding effort at all for anything beyond walking pace.

Basically if you ever think you may not be able to stop in time, don’t bother with the brakes—just bail out!

We try turning on the switch to the Miller lighting set, and are most impressed by the brightness of the beam … no, you’re right, that wasn’t exactly true, we just dreamt it … they didn’t work at all.

The Phillips Motorised Cycle with braced rigid-fork was introduced in October 1954 at £49–15s (inc. purchase tax), but by September of 1955 the same machine was being listed for £55–12s–10d, reflecting quite a high annual inflation rate running around 11% at this time.

The following month brought a Mark 2 Motorised Cycle fitted with a telescopic fork set, having simple greased springing for suspension, with no damping function. The P36X designation and £55–12s–10d price tag remained the same for the new sprung-fork model, which succeeded the original rigid Mark 1.

At the Earls Court Motor Cycle Show in November 1955, Phillips introduced a P39 Rex powered two-speed Gadabout moped, which employed the same design of telescopic fork as the Motorised Cycle.

List price of the P36X Motorised Cycle rose to £57–17s–11d in 1956, and though the Gadabout moped was costing over £11–7s more, it did seem to be attracting better sales.

Simply having the cheapest purchase price was seemingly no longer the prime factor to consider in a transport purchase. The post-war years of austerity were coming to an end, and now that the buying public was acquiring more disposable income they were choosing to buy better-built machines, so favour for a cyclemotor was swinging toward the moped.

In June 1957 a Miller magneto-set replaced the original Bosch generator unit.

The P36X Motorised Cycle remained on listings up to November 1958, when it was withdrawn in preparation for introduction of the new P40 Panda moped in February 1959.

The original P36X Phillips Motorised Cycle with the old-fashioned ‘braced’ rigid-fork set was only produced for a year, and sold well in its brief moment because its market timing was good, and the bike represented a good looking and quality complete cyclemotor of the time for the right price (below £50).

Just a year on, and the Mark 2 Motorised Cycle with its better functional (though uglier) telescopic-fork set looked to have lost the balance of style, and the fashion toward better built mopeds as complete machines was fast eclipsing the DIY economy of the cyclemotor.

The P36X Motorised Cycle was very obviously a cyclemotor, just being sold in complete form like a moped, which was no different from a number of other cyclemotors of the time: Cairns Mocyc, Vincent Power Cycle, BSA Winged Wheel, BMG & Presto Mosquitoes, etc. All were shortly to become overwhelmed under the relentless march of the all-conquering moped.

The Phillips came along quite late in the cyclemotoring day, just on the cusp of the dawn of the moped era, so as a late ‘transition’ machine, was never destined to have much future. Despite being sold as a complete vehicle, it was very clearly and distinctly bicycle based, and the subsequent addition of the telescopic fork set on the Mark 2 didn’t change the fact that it was still based upon a bicycle—and the cyclemotor was fast becoming history.