In May 1926, the

French Circulaire 32, Série

B designated a new Bicyclette

à Moteur Auxilaire (BMA) specification, intended

for vehicles: under 30kg, less

than 30km/h performance,

below 100cc capacity, and

fitted with pedals, to qualify for exemption from

registration. Effective from the age of 14+, the

classification neither required a driving licence, roadworthiness

testing or vehicle tax, and the order became effective on 12th

September 1926.

In May 1926, the

French Circulaire 32, Série

B designated a new Bicyclette

à Moteur Auxilaire (BMA) specification, intended

for vehicles: under 30kg, less

than 30km/h performance,

below 100cc capacity, and

fitted with pedals, to qualify for exemption from

registration. Effective from the age of 14+, the

classification neither required a driving licence, roadworthiness

testing or vehicle tax, and the order became effective on 12th

September 1926.

At this time however, there wasn’t really any significant interest to actually produce machines compliant to this new specification. Small capacity engines of the time were fairly ineffective and not particularly commonplace, and people who could afford to buy motorised vehicles would invariably invest in a more capable motor cycle or car.

The economic climate however began to change, commencing with a fall in American share prices which started around 4th September 1929, and hit worldwide news as the infamous US stock market crash of 29th October 1929, which came to be known as Black Tuesday. This became the origin of the most severe commercial downturn of the 20th Century, subsequently becoming more widely known as The Great Depression.

Ripples from the American market crash spread out across the globe, affecting European countries in 1930, and by 1931, France too was gripped by the fist of economic depression, though the country’s high degree of self-sufficiency somewhat cushioned the effects that were having a far greater impact on some of its European neighbours.

Looking at the changing situation, Peugeot designed and launched its first Bicyclette à Moteur Auxilaire in 1931, which was introduced as a pair of 98cc models within the 30kg weight and 30km/h performance to better suit the changing market demands of the time for small capacity economic transport. Peugeot presented these machines as Vélos-Moteur, which actually translates as ‘Moped’, a term later destined to become adopted as the generic name for small pedal assisted machines, though these early BMAs more commonly came to be known as Vélomoteurs.

During the war years, the French Vichy government issued a decree on 5th June 1943, which technically re-defined the original BMA specification, and created a new Bicyclette à moteur de secours under 50cc category (later called Cyclomoteur). Considering that France was ‘occupied territory’ at this time, it was somewhat surprising that, even during the war, a number of French companies actually started developing models to this new specification, with the view towards making compliant machines following liberation, when Europe might start getting back to business again.

Even

before the end of World War Two it was looking possible that the

next European ‘economy capacity’ could be within this

newly defined sub-50cc

group, and Peugeot cautiously decided not to invest in resuming

production of its old vélomoteurs, but to wait and see

where the market was going. During these austere and

impoverished post-war times, it was indeed the new

sub-50cc group that proved

to be attracting the greatest demand, so Peugeot tentatively

tested the new cyclemotoring market with a cycle fitted with a

VAP4 engine.

Even

before the end of World War Two it was looking possible that the

next European ‘economy capacity’ could be within this

newly defined sub-50cc

group, and Peugeot cautiously decided not to invest in resuming

production of its old vélomoteurs, but to wait and see

where the market was going. During these austere and

impoverished post-war times, it was indeed the new

sub-50cc group that proved

to be attracting the greatest demand, so Peugeot tentatively

tested the new cyclemotoring market with a cycle fitted with a

VAP4 engine.

The VAP (Verots–Androit Propulseur) was made by ABG; ABG was primarily an engine manufacturer, and was independently selling the VAP4 as a cycle attachment engine kit, so Peugeot would have to market its version in a different manner or there would be no profit in it for them.

The Peugeot PHV-25 cyclemotor of 1949 was, therefore, sold in the form of a complete machine, as a Peugeot built mixte framed cycle fitted complete with the VAP4 engine.

Peugeot’s association with ABG led to the development of the VAP5 roller-driven motor for mounting beneath a cycle bottom bracket, this engine being exclusively made for Peugeot to power their forthcoming BMA25L and BMA25GL models, which were first shown at the Paris Salon in October 1950. Being a development of the VAP4 engine, the VAP5 had several parts in common with the earlier deflector-top piston motor. Again the cyclemotor models were sold as complete machines, with the frames made by Peugeot to maintain their input. The BMA model prefix was clearly intended as a reference back to the old Bicyclette à Moteur Auxilaire specification.

BMA25 variants were widely sold in an aggressive campaign to saturate the market under several Peugeot owned brands as Aiglon, Automoto, Griffon model 525, Météor, Peugeot’s own label, and Trophée de France.

The siege of the cyclemotors had begun, and Peugeot was intent on establishing a goodly slice of the action.

The BMA25 range was only sold for just the single season of 1951, being superseded by a new cyclemotor range later in the autumn.

The new Peugeot ‘Bima’ was launched at the Paris Salon in October 1951, however, this time it wasn’t just the frames that Peugeot built; the Bima cyclemotor engines were now also produced within the Peugeot group, and were planned to be similarly sold under other Peugeot-controlled brands as the company sought to secure its position in this competitive sector.

The cycle chassis was pretty much a derivative of the earlier BMA25 apart from detail changes of different toolboxes, inverted levers, and an easier-to-reach engagement lever. Bimas employed a Wageor V15A magneto with internal HT coil or a Morel VBS50 magneto with external HT coil. Neither type had generator coils, so a Soubitez cycle dynamo was fitted to power the lighting set. Peugeot presented its own branded Bimas in two models: the Luxe with rigid fork and calliper brake at the front, and the Grand Luxe with tele-fork and drum brake at front. A further Standard model was introduced during 1952; this was like the Luxe, but had no mudguard valences, no front rack, no toolboxes, and calliper brakes at front and rear.

On 1953 models the engagement lever was moved to the top tube of the frame on Luxe and Grand Luxe versions.

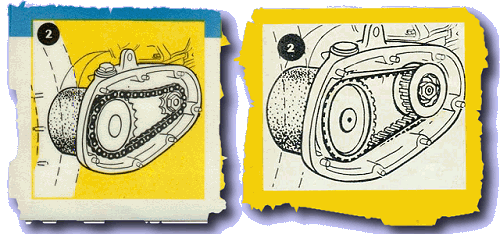

Bima models at the 1954 Paris show now introduced an

ABG magneto set with internal generator coil, and a toothed belt

primary drive instead of the earlier chain in an oil bath

casing. There were also changes in fittings to better

define the models: the Grand Luxe acquired a horn, while the Luxe

lost its toolboxes and mudguard valences, but gained a telescopic

fork set.

Bima models at the 1954 Paris show now introduced an

ABG magneto set with internal generator coil, and a toothed belt

primary drive instead of the earlier chain in an oil bath

casing. There were also changes in fittings to better

define the models: the Grand Luxe acquired a horn, while the Luxe

lost its toolboxes and mudguard valences, but gained a telescopic

fork set.

We’ve now reached the point to introduce our featured machine, since we think it dates from around this time. This appears to be the basic Standard model with a rigid fork and basic calliper brakes front and rear.

Our Bima features a Mixte style frame, but with elegantly curved tubes up to the headset to allow more ‘step-through’ clearance, where the usual Mixte frame would employ straight tubes. An aluminium ‘owner’s plate’ is tagged to the saddle stem tube at the lower frame, hand stamped E.Chadet, 3 Berbisey, Dijon. While not having to be formally registered, at one time French mopeds were required to carry a plate giving their owner’s details.

The mattress-sprung saddle frame still wears its original cream coloured plastic cover, branded Henri Gauthier 28 Pacific Saddle with matching Pacific tool bag mounted off the back of the saddle.

There’s a prop-stand mounted on the lower frame

stay to back & left, which even allows full rotation of the

pedals when you’re backing the bike (Raleigh take note: re

RSW16).

There’s a prop-stand mounted on the lower frame

stay to back & left, which even allows full rotation of the

pedals when you’re backing the bike (Raleigh take note: re

RSW16).

The wheels have 21-inch rims fitted with 600 × 50B tyres, the front being a Dunlop-moulded ‘Montluçon France’, and the rear a Michelin Type-Y heavy-duty roller-drive ‘Motorette’ rib type.

Further original factory fittings include a rear carrier with pannier support frame, and ring loops at the hub point to secure the bottom ties for fitting pannier bags.

There’s an eccentric operation drive engagement lever down the right side of the saddle stem tube, down to engage, turn 180° to up for disengage, whereupon the single-speed pedal drive ratio gives a leisurely pedalling pace for easy use as a bicycle.

Our Bima displays the early type chain primary drive within an oil bath chain case on the engine, but also sports the ABG (VAP) magneto with internal HT and lighting generator coil, so it would appear that this magneto set had already been introduced to production before the Salon, which features are probably going to date our bike around Autumn 1954.

The

Gurtner 10mm carburettor has an

unusual enrichment mechanism, which rotates the air slide top to

raise the needle within the throttle slide, though operates

conventionally from a small trigger under the left handlebar.

The

Gurtner 10mm carburettor has an

unusual enrichment mechanism, which rotates the air slide top to

raise the needle within the throttle slide, though operates

conventionally from a small trigger under the left handlebar.

The fuel tap oddly seems to have opposite operation to Mobylette taps, appearing to pull for on/push for off.

With the Ali–Saker twistgrip turned forward to decompress, pedal away to get the engine turning, twist back the throttle, keep pedalling and trigger the choke to rouse the motor to cough into life. A few hesitant firings mean a little persistence is required, and light pedal assistance to aid the cold combustion, but within a few seconds the Bima motor is able to take over and we get underway.

Torque from the engine is reasonably capable from even low revs, which pulls under its own steam pretty much right from the off.

As the engine works some heat into the castings our pacer reports the bike readily maintains up to 25mph along the flat under neutral conditions in still air, but fading back to 18mph against light inclines. The long, light downhill run in a crouch got us up to a best of 29mph before the revs disrupted into a tizzy of four-stroke firing as the exhaust and transfer porting ran out of range, which indicated the bike’s ceiling.

It

proves particularly difficult to operate the drive engagement

lever in a clutching capacity since its mounting position low

down on the right-hand side of the saddle stem tube is most

awkward to reach with the left hand while controlling the

throttle and handlebars with the right hand. Generally you

try to judge the pace up to junctions so as not to have to effect

a stop, where you’d then have the choice of either coming

to a halt on the decompresser, then restarting; or struggling to

clutch the engagement lever to keep the engine going.

It

proves particularly difficult to operate the drive engagement

lever in a clutching capacity since its mounting position low

down on the right-hand side of the saddle stem tube is most

awkward to reach with the left hand while controlling the

throttle and handlebars with the right hand. Generally you

try to judge the pace up to junctions so as not to have to effect

a stop, where you’d then have the choice of either coming

to a halt on the decompresser, then restarting; or struggling to

clutch the engagement lever to keep the engine going.

The Bima engine proves very docile in running down to low revs, so does help with the pace judgement, then pulls cleanly again once commanded by the throttle-up. The flexibility of the engine right through its range did much to compensate for the direct roller drive transmission.

Like many cyclemotors, Bima runs best under a constant load with the throttle on, where it relentlessly steams along, and you can easily forget its clutching limitations.

Do the lights work? Click the switch on the top of the headlamp shell—and yes they do, but that measly 6V, 6W MES headlamp bulb with continental market ‘anti-dazzle’ yellow coating was certainly never going to blind anyone—there seems almost no prospect of seeing anything at all with that illumination.

Stopping

abilities were actually a little better than we expected despite

the cycle-style front and rear calliper rim brake brakes, but we

imagine those open blocks could become somewhat

‘challenging’ under wet conditions.

Stopping

abilities were actually a little better than we expected despite

the cycle-style front and rear calliper rim brake brakes, but we

imagine those open blocks could become somewhat

‘challenging’ under wet conditions.

Overall, we were quite impressed by the way our Bima performed. Several people had said they were good bikes to ride—and they’re absolutely right!

The variously branded Bima models proved very popular, and by 1956, trade rankings put Peugeot at third place (after VéloSoleX and Mobylette) in the French moped market, with sales approaching half a million.

The Grand Luxe was upgraded to the Grand Luxe II C this year, with a new monotube frame.

The monotube frame design subsequently was adopted across the derivative branded range in a wide selection of differently badged models with a bewildering variety of various finishes. Branded Bima variants were also made under the badges of Aiglon, Ruche, Christophe, Indenor, Terrot Lutin models (Lutin meaning goblin: Lutin Standard, Lutin Ville, Lutin Luxe), Magnat–Debon (Fauvette luxe, Fauvette grand luxe), Météor, Automoto (‘Le Furet’ models CGU, CGL & CGR), and Griffon.

Possibly because Peugeot started its introduction to cyclemotoring by selling dedicated cycle chassis fitted with factored engines, they only supplied cyclemotors as complete machines, and never sold their Bima motors as attachment engine kits. Even in the early days of cyclemotoring the French market seemed to develop more toward a preference for complete machines rather than clip-on engines for bicycles, so lines were already becoming blurred as to where the technical definition of a cyclemotor ended, and where a moped started.

Even in Britain, many attachment engines ended their days being sold as manufacturers’ complete machines (bicycle with fitted engine), which may have been considered by some as the threshold of becoming a moped.

The French sub-50cc market evolved somewhat differently, due mainly to the widespread popularity of sold-as-complete-machine roller drive cyclemotors accounting for well over 50% of the market into the late 1950s, with home producers like VéloSoleX, the Peugeot brands, VeloVap, Motobécane BG models, and Chapuis Frères’ Presto Mosquitoes maintaining significant shares over a period where cyclemotor sales had practically collapsed in other European countries under preference for the moped.

Peugeot could also see the way the tide was turning, and began presenting its own moped models from 1957.

It was becoming apparent that the post-war cyclemotor boom was coming to an end, as sales were increasingly moving across to more complete and dedicated machines. Society was emerging from the residual effect of post-war blues, and people began to find a little more disposable income, and then graduated on towards the next big thing: the moped!

Many of the marques that Peugeot owned had historically been lucky to enjoy a great deal of independent operation, but into the later 1950s times were beginning to change, and the traditional old brands were being whittled away. Aiglon and Ruche branding finished in 1954, Griffon in 1955, Magnat–Debon in 1958, Terrot was closed in 1961, and followed by Automoto in 1962.

It was most remarkable that Bima cyclemotor production continued until 1964.