It might be hard to produce a sequence on classically French motorised cycles without considering this machine.

Its imprint is ingrained in stereotypical imagery over several decades, and few would deny any claim that it has truly earned its place as a national icon.

Marcel Menneson and Maurice Goudard founded their Solex Company at Paris in 1905, initially to manufacture vehicle radiators. Following the Great War, the Solex radiator business fell away, so the company bought the patent rights of Jouffrett and Renée to establish manufacture of carburettors instead. The business also diversified into making measuring equipment between the wars.

With France being overrun by the Axis powers in June 1940, it wasn’t long before fuel supplies started becoming restricted, so Solex set about the idea of trying to develop a simple and economical micro capacity engine to run on a bicycle. The first 38cc prototype motor with direct drive was completed in 1941 and mounted on a cycle frame for trial purposes, but for obvious reasons, the wartime period was not a particularly suitable time to develop the machine to production.

The way forward, however, was paved on 5th June 1943, when a French Vichy government decree re-defined the original Bicyclette à Moteur Auxilaire (BMA) specification into three newly qualified motor cycle categories as Motorcyclette over 125cc, Vélomoteur between 125cc and 50cc, and Bicyclette à moteur de secours (later called Cyclomoteur), under 50cc.

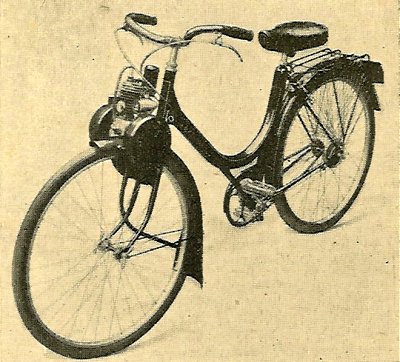

With the stage now set for a new class of vehicles below 50cc, and growing demand for low cost and reliable economy transport after World War 2, the first production model Solex motorised cycle was manufactured in 1946. Engine capacity was now increased to 45cc for 0.4bhp at 2,000rpm, with fixed direct drive to the front wheel through a grit roller, and sold as a complete machine mounted on a swan-neck cycle frame.

Introduced as VéloSoleX, from a combination of the pre-war Vélomoteur machine and the Solex Company, the vehicle became an instant success in its home market.

Having established a Solex carburettor division in North London, a few imported models began to reach Britain in 1948 and, to commence distribution of machines into the UK, the company registered Solex Cycles Ltd, Solex Works, 223–231 Marylebone Road, London NW1. The British operation progressively phased in more home-manufactured parts, and by the following year the transition process was well underway.

Developed and introduced in 1951, a latching device now enabled the drive motor to be disengaged from the wheel, which could be effectively operated as a clutching mechanism, giving the machine a fair degree more operational flexibility. The original 45cc motor continued until 1953, when the first new 49cc, 0.5bhp engine models appeared on a VéloSoleX 330 series cycle, now fitted with a press-formed rear carrier. Series 330 continued up to 1955, to be replaced by model 660 up to 1957. The VéloSoleX never managed to achieve the popularity in Britain that the machine did in its home country, though this was hardly surprising since the licensing regulations were wholly different. Production of the British Solex ceased as a new 1010 series model with more detail developments was introduced in France.

A change to 19-inch wheels in 1958 brought in the 1400 designation, and 1700 series in 1959 with fan-cooling, a larger capacity fuel tank to 1.4 litres, and option of an automatic clutched version.

Now arriving at our point of entry, we have a model 1700 VéloSoleX as our feature tester.

This is a fairly recent French market immigrant, seems to date around 1960, and looks to be the base version since it has direct drive with no automatic clutch.

By this point the roller-drive cyclemotor was pretty much an extinct animal in the UK, so the VéloSoleX would have appeared as a particularly outdated and obsolete machine if lined up in a British showroom of the day. Such a primitive machine may have struggled to find buyers at this time—but there were no official imports, so you might have been somewhat challenged to find an example if you actually wanted one!

Even before you get to ride a VéloSoleX, just handling the bike creates an ‘odd’ impression.

When you push the bike forward to nudge it off the stand … it doesn’t! Because all the cycle weight is up front, and the back of the bike is so feather light, the stand just skips over the ground and doesn’t fold up. When pushing forward, you either need to press down on the saddle, put your foot in front of the stand, or lift the frame by the saddle and flick up the leg.

When you put the bike back onto the stand and let go of the bars, the headset usually slews right round either way since there are no steering stops. That is the classic VéloSoleX pose you so often see, but the way it does this can be annoying since the wheel sticks out, and it looks really gormless.

These things happen because of the weight distribution, so we put the bike on the scales: back 1 stone 10 pounds, front 2 stone 8 pounds.

Bikes are usually balanced the opposite way round, heavier at the back than the front, which is why the VéloSoleX handles rather differently and feels odd.

The rear frame comprises very lightweight pressed steel, with all the components bolted together, while the mainframe spine comprises a round formed tube, and features the only welded joint to the steering head.

The front forks are single-sided steel pressings with an open back, seemingly bolted to the bottom yoke.

The whole impression is … well, Meccano!

Tyres are 23×2 on 19-inch Endrick pattern (square sided rims), since front and rear calliper brake blocks are required to work on the sides. The rear wheel is conventional 36 spokes, but the front only has 28 spokes, so there’s a special rim if you need to replace it.

Perched on top of the front mudguard is an old black crow … oh no, sorry, that’s the engine!

There seemed to have been a real Henry Ford theme going on with VéloSoleX since, right from day one, the only available colour was black—and there was plenty of black on the bike and all over the engine.

It would take VéloSoleX 20 years to discover colour.

The Solex motor is characterised by cooling fins rising from a horizontal black cylinder, which is laid across the front wheel. A particularly easy-access spark plug sticks out the front of the fins, and the cylinder head is topped with a shiny aluminium air filter cover. A large lever christened by a ball-ended knob rises behind the engine and latches into a catch off the steering head—you know what that is don’t you? Yes, it’s what you might call—the clutch!

The Solex engine drives by a grit roller onto the front tyre, and the lever engages or disengages the roller by lowering or raising the engine on a pivot. There are many words to describe this system … some call it simple … some call it primitive, but that’s how it works.

Since front tyre wear is obviously going to be an issue, the special Mororette tyre has a heavy duty radial-rib pattern and is more deeply treaded to better cope the abrasive drive from the grit roller, which would probably gobble up conventional tyres in double-quick time.

Arranged to right of the wheel, the engine is overhung design, so generally expected to be operating at relatively low revolutions. The grit roller is disposed in the centre to drive the wheel, and flywheel mag-set to the left hand side, so there’s hardly any likelihood of heat transference affecting the ignition. The mag-set contains an internal coil to generate a modest output and illuminate a cycle tail light and headlamp mounted in a plastic cowling over the front of the motor. The lights are operated by a neat and simple integral flip switch—just off/on, but maybe not enough power to stretch as far as an electric horn since the handlebars only mount a cycle bell as means of warning.

Completing the ‘black-transverse-tube’ look, the fuel tank is fixed to the right end of the crankcase, and very plainly below the carburettor, which is set above and behind the cylinder. Since Solex petrol is governed by the normal laws of gravity that prevent it flowing uphill, there’s a mechanical pump on the front of the crankcase, which constantly operates as the engine turns, to raise fuel to the carburettor. Now this instrument doesn’t quite operate in any normal sense, with a float valve regulating the fuel supply into the carburettor—oh no! It doesn’t have any float at all!

Since the engine uses less fuel than the pump constantly delivers, it has a weir system, which constantly overflows excess fuel to drain down a tube and back into the tank, while the engine draws whatever it requires through the main jet. The carburettors only moving part is a rotating barrel to regulate throttle control, but sprung fully open so the motor normally runs on full throttle!

No, that isn’t a typo and you didn’t read that wrongly, the VéloSoleX does normally run at full throttle, and you thumb a little lever to de-throttle the engine if you want to slow down. Yes, it’s completely backward to practically any normal vehicle control. Pretty much every other vehicle in the world has a throttle operation that you open if you want to go faster, but VéloSoleX has an operation that assumes you always want to be travelling at full speed, then operate the throttle to slow down! You probably have to be French to understand the thinking behind this, but we’ll try to give it a go.

The idea was that the VéloSoleX could be simply operated and ridden by anyone as easily as riding a bicycle that you didn’t have to pedal—anyone who knew absolutely nothing about starting and controlling any motorised vehicle should be able to get on and ride it straight away … but to any other motorist this probably seems completely nuts!

There’s no fuel tap and no ignition switch, though there is a choke control lever on the back of the carb, and positionally indicated on the air filter by an arrow "départ". We’re not French, so we don’t know what that means?

To start up, undo the "clutch" lever from its latch so the motor engages drive, thumb the throttle trigger right back and it opens a decompressor to get the engine spinning more easily, then pedal away and just let go the trigger to start the engine … nope, we’re still pedalling and it hasn’t started.

We phutter to a halt and try the choke lever switched across to the tail of the arrow. Decompress, pedal away, let go the trigger … and yes, the engine chugs into life. After coughing along the road a little, reach forward to switch the choke lever across, at which the motor clears and pulls away.

There’s not really acceleration as such, just a gradual lumbering build-up of momentum … it feels as if you want to open up the throttle, except it already is!

Speed picks up better if there’s a slight downhill gradient, but if there’s a slight uphill gradient then it’ll start slowing down, and you might find yourself thinking about pedal assistance.

General running speed in still air averaged around 15 to 16mph on the flat and up to 23mph on downhill run.

With normal running at full throttle, the rider doesn’t need to concern themselves with regulation of the controls, and there isn’t really anything much to do other than point the bike in the required direction, so you have plenty of free time to look around and appreciate the scenery … look at all the litter along the verge…cola can, fried chicken wrapper … wonder if someone is missing that hubcap?

Maintaining a consistent pace simply isn’t possible since the feeble motor readily slows against the slightest gradient or headwind, like a leaf on the breeze of life, subject to force of nature and geography.

The normally ‘clumsy to operate on an autocycle’ inverted brake levers don’t seem too bad on the VéloSoleX, since there isn’t really much in the way of other controls to complicate the operation. Old autocycles tend to become difficult with inverted levers, mainly due to handlebar clutter, and changing from throttle and clutch levers to braking, but the Solex proves much easier to grab the levers. Where it’s not so good is that you’re trying to hold it back against the full-throttle motor if you haven’t de-throttled. Simultaneously thumbing back the throttle trigger while also operating the front brake lever with your fingers, isn’t a natural dual-control operation that comes readily, and will probably take a bit of practice before you quite master the function.

Thumb the throttle trigger back too far in the heat of the moment, and it works the decompressor so the engine cuts out. Accidentally release the trigger and the engine throttles up again—it can be easy to get in a tizzy if you’re not familiar with the control operations.

To help (or further complicate) matters, there’s a secondary ‘damped’ trigger that overrides the main throttle lever, you can set the damped trigger to hold back the throttle lever if you want to go slower, or trim the running back to tick-over if the engine is raised from drive. Thumb either lever again to re-open the throttle—it’s all very backward stuff. Quite alien.

The heavy-gauge, cycle-style calliper brakes are generally adequate for slowing VéloSoleX from its generally cycle-like performance, and their operation is often accompanied by the familiar cycle-brake creaking and groaning noises to make cyclists feel at home.

Handling is, well, how can we put this? In motor cycling terms—it’s just terrible! The light and rigid cycle frame with all the weight up front is a pretty diabolical combination. In terms of riding balance, it doesn’t have any. You can signal OK with one hand on the bars, but to hands-off is pretty much dicing with disaster.

The headlight (still fitted with continental yellow bulb) proved brighter than expected (though the tail light bulb had blown, so maybe it was receiving a little more wattage than usual). An amusing moment when running the machine at night came while ‘clutching’ off the motor, to discover the headlamp beam tips back with the engine and becomes a spotlight beam into upstairs rooms! Er, sorry about that (to the neighbours).

Some of the engine components are made out of unlikely materials. The cast iron cylinder and aluminium head are quite ordinary, but the employment of die-cast zinc for the crankcases is rather unusual. It’s presumed this may be related to the Solex background as a carburettor manufacturer, and a familiar material that they were already structured to process. Zinc diecasting is performed at appreciably lower temperatures than aluminium, and the equipment would not accommodate the change of material. The zinc crankcase castings seem to work effectively enough, but this metal is generally not a common specification for this application. Motobécane used the material for some of their very early AV3 crankcase castings but soon switched to aluminium, and the only other cyclemotor engine we can readily think of that also chose to employ Zinc die-cast crankcasings, was the Cymota derivative of the VéloSoleX engine.

Solex engine cooling is a quite unfathomable ‘belt & braces’ arrangement.

The cylinder finning is prominently presented right in front of the machine, no problem there at all, a lovely clear airflow … but there’s also a fan-cooling setup—of sorts!

Most fan-cooling arrangements are generally what’s described as ‘forced-air cooling’, with ducted draft from a fan … but Solex isn’t quite there?

Yes, there’s a fan on the mag flywheel, and the plastic moulded mag cover features an air outlet directed towards the cylinder—but no ducting, so there’s a big gap between the fan outlet and the cylinder! What’s that about?

Solex 5000

Maybe you’ll get a gentle breeze vaguely wafting across towards the cylinder when the bike’s stationary, but wholly ineffectual when the bike is moving and the airstream takes over. It’s a mystery!

It was like they just stuck it on as a feature because they could, and it wouldn’t actually cost anything—but seemingly pointless?

The Solex exhaust is another interesting contrivance, with over 2 feet of 5/8-inch diameter pipe snaking its way from the back of the engine, down and around to bottom/back of the front mudguard, where it terminates in a round silencer box. Unlike the alternative fan-cooling though, there appears some purpose in the tortuous exhaust routing, since it theoretically places the tailpipe to vent its oily two-stroke emissions after the front wheel and avoid deposits on front braking components and the rider—except it doesn’t quite seen to work like that, since the exhaust smoke swirls around and the front rim gets oiled up anyway. Never mind, the intention was good.

Solex 6000

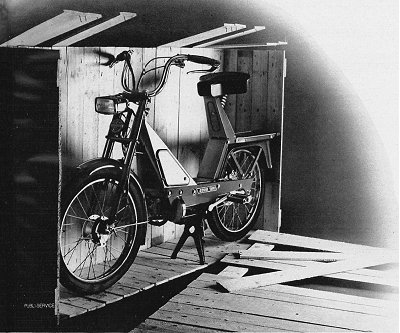

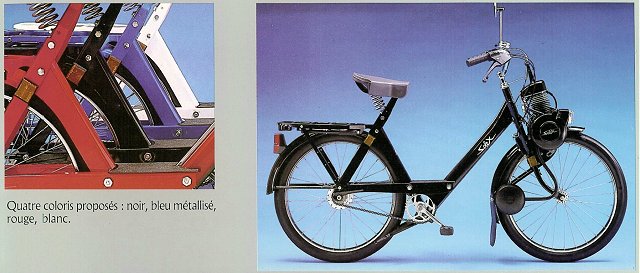

The 1700 model was superseded by S2200 with 0.7bhp motor in 1961, S3300 with a rectangular fabricated sheet section frame in 1964, S3800 in 1966 with the first ever colour options of red or blue for the Luxe, and white for the Super Luxe version. Up to this time all VéloSoleXes were only available in black.

With a number of further developments like the change to a conventional accelerator control, the 3800 continued in production until 1988, but was joined by a new 5000 model in 1971. This version was equipped with smaller 16-inch wheels, available in blue, orange, yellow and white, with stainless steel mudguards.

A 5000 PliSolex foldable version was also available, with hinge on the central beam frame, and easily dismountable engine for transportation.

There was further a 48cc, 1.4bhp 6000 ‘Flash’ machine that wasn’t even remotely as fast as its name may suggest. Maybe technically interesting in a peculiar sort of way, with an angular press-formed frame and conventionally placed motor, though with shaft drive, and an electric fan-cooled engine—but slowwwww!

The Solex carburettor division was taken over by Matra/Dassault in 1973, traded through Magnetti Marelli, Renault, and Motobécane in 1974. In 1983, Motobécane was bought by Yamaha, to become known today as MBK.

French production ended in 1988 with over 7 million units produced, but continued under license in China, and as Impex in Hungary till 2002.

In June 2004 the Solex mark was purchased by the French CIBLE group, with some production returned to France in 2005.

In 2006 CIBLE launched the e-solex electric cycle, designed by Pininfarina and made in China with a 400 Watt induction motor capable of 35km/h and 30km range,

Traditional style motorised VéloSoleX S4800 models returned to manufacture again in France from 2007.

2009 introduced a new e-solex2 electric cycle version with Li–polymer battery.

Over 8 million VéloSoleX branded units have now reportedly been sold.

Solex discovers colour

Next—Lost somewhere in the great chasm between the Cyclemotor and the Moped, this started as one machine, then became another … and that’s why we call this Re-Cycling

This article appeared in the

January 2013 Iceni CAM Magazine.

[Text and photos © 2012, 2013

M Daniels.]

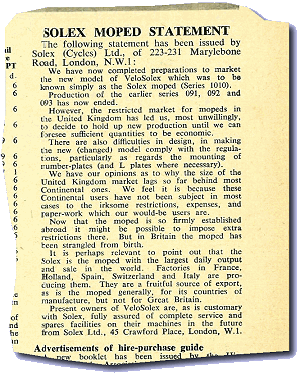

This statement from Solex (Cycles) Ltd of Marylebone Road, London appeared in the 31 August 1957 edition of Motor Cycle and Cycle Trader:

We have now completed preparations to market the new model of VeloSolex which was to be known simply as the Solex moped (Series 1010).

Production of the earlier series 091, 092 and 093 has now ended.

However, the restricted market for mopeds in the United Kingdom has led us, most unwilingly, to decide to hold up new production until we can foresee sufficient quantities to be economic.

There are also difficulties in design, in making the new (changed) model comply with the regulations, particularly as regards the mounting of number-plates (and L plates where necessary).

We have our opinions as to why the size of the United Kingdom lags so far behind most Continental ones. We feel it is because these Continental users have not been subject in most cases to the irksome restrictions, expenses, and paper-work which our would-be users are.

Now that the moped is so firmly established abroad it might be possible to impose extra restrictions there. But in Britain the moped has been strangled from birth.

It is perhaps relevant to point out that the Solex is the moped with the largest daily output and sale in the world. Factories in France, Holland, Spain, Switzerland and Italy are producing them. They are a fruitful soutce of export, as is the moped generally, for its countries of manufacture, but not for Great Britain.

Present owners of VeloSolex are, as is customary with Solex, fully assured of complete service and spares facilities on their machines in the future from Solex Ltd., 45 Crawford Place, London, W.1.

VéloSoleX were imported into the UK in the 1970s, when a few came in via Harglo Ltd who, at that time, imported the Dutch Batavus range of mopeds. From 1974 to 1978 I sold Batavus mopeds, which were an excellent product. At this period I sold three VéloSoleXes, but they never were likely to become popular in the UK market for reasons outlined in Mark’s article. They just were not what we in Britain expected from a moped; plus our ridiculous legislation regarding the use of a 50cc powered two-wheeler hardly promoted their use.

Frankly, I personally found riding one frightening due to lack of performance and their bizarre handling. I have however worked on quite a few during my 60 years on two wheels and the whole design concept is, shall we say, fascinating.

Sincerely,

Jim Lee.

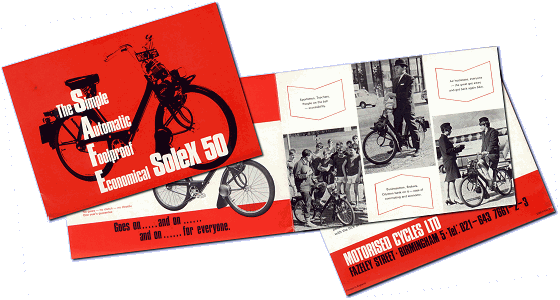

UK Solex brochure from 1968

No French sequence could possibly be complete without a VéloSoleX. Our featured 1700 came from owner Mark Cole at Brentwood, and went through the workshops for service and registration in April 2012. The workshops have previously seen several of these Solex machines passing through, though we hadn’t really been inclined to bother with any for feature before, but this seemed a good and original example, and worked nicely once overhauled—so thought we’d give it a chance.

To be honest, the VéloSoleX is rather like Marmite … you either love them, or hate them. There is no in-between.

It’s certainly a classic French icon, and there’re quite a few people who pick them up out of novelty and interest, despite knowing nothing about them, or how they work … or how slowly they go. A VéloSoleX initiation can sometimes be both a shock, and a disappointment, and it’s often not unusual to see these machines returning for sale again just as quickly as they arrive—but in the end may hopefully find someone who will appreciate their somewhat ‘odd’ qualities.

The VéloSoleX was technically interesting … alternative … and seemingly better engineered than its dreadful Cymota clone that we tested earlier in Front Wheel Drive … but it does seem to require some ‘unknown quality’ to be able to relate to a Solex?

Le Corbeau/The Crow article title was a play on VéloSoleX only being available in black until 1966, and our special ‘double-take’ crow picture was obviously another product of Andrew’s digital dabbling.

The first model was launched in 1946, and it took VéloSoleX 20 years to discover colour!

Though the workshops spent several hours sorting the bike out, actual production costs on this article were negligible since again, the bike was delivered and collected by the owner, so quite a practical ‘something for nothing’ feature as far as the accounts were concerned.

Sponsorship credit went to Graham McLean in Victoria State, Australia … another small contribution going an even longer way!