Power Pak Moped

Trying to research enough general background for some of our obscure machine articles can often prove difficult enough in itself, so tracking down one of the rare examples really helps with the analysis. Beyond this, when some of these vehicles become so obscure that they barely even existed in the first place—things can become pretty tricky! In most cases these are going to be prototype show models that never actually made it into production, and where there are believed to be no known survivors, that rather rules out any prospect of a road test!

That doesn’t mean however, that we can’t produce a feature—it just demands a different type of presentation.

The machines covered in this planned series of articles may presently be assumed to be extinct—but it doesn’t mean some of them couldn’t be brought back. Unlike biological organisms, a machine can be recreated if the component parts can be identified, and your name needn’t be Baron Von Frankenstein to build a replica!

So with the stage set, what better machine to start with than that perennial puzzle: the Power Pak Moped. Announced to the press in late 1955, the grandiose plans of 1,000 bikes a week mysteriously seemed to evaporate into thin air...

Power-Pak 49cc clip-on cyclemotors were introduced to the motor cycling press in April 1950; price listed for sale at £25, and offered by Sinclair Goddard & Co. Ltd, 162 Queensway, Bayswater, London SW2.

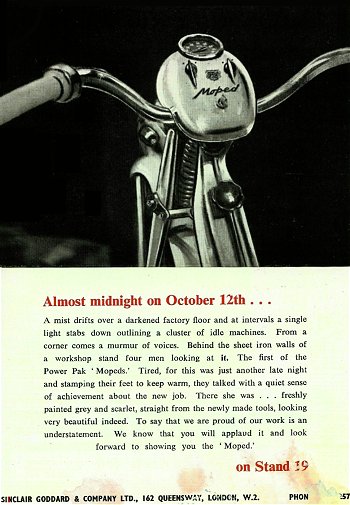

Presentation of the Moped in Motor Cycling on

October 27th, 1955

Considering the cyclemotor remained on sale for a decade, apart from the published adverts and literature, it’s quite remarkable that practically nothing is known about the people that actually produced the kits!

First announcements of the cyclemotor referred to both Power Pak Engineering Co Ltd, and presented Sinclair Goddard as ‘sole concessionaires’ and ‘distributors’, suggesting this arm of the business might have been created for marketing the kit, and possibly wasn’t the actual manufacturer.

Sited just down the road from Whiteleys department store, the 162 Queensway, Bayswater address is now a DIY Tool Store, and the area is mainly given over to retail and housing.

In Sinclair Goddard’s day it’s likely that the ground floor was arranged as a showroom with offices, and probably some workshop facilities for light servicing. Given this site is little more than a relatively small shop with flats above and behind, it would seem rather unlikely that the premises were used for the actual manufacture of engines, so it appears the cyclemotor kits were being made somewhere other than Sinclair Goddard’s registered address.

When you take one of the units apart there’s no question regarding the nationality of its primary components, British manufactured bearings, Heplex piston, Wipac magneto set, Amal carburettor—it’s clearly of UK origination.

The original direct-drive cyclemotor continued up to 1953, at which point it was re-titled as the ‘Standard’, and was joined by a new ‘Synchromatic’ clutched version priced at £27–6s–0d.

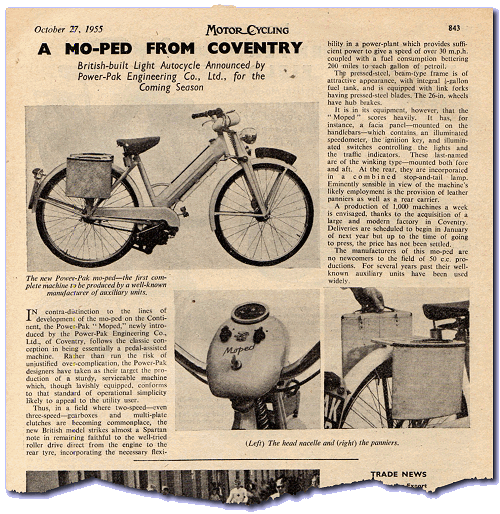

Announcement of the Moped in

The Motor Cycle on October 27th, 1955

1954 listed a ‘New Standard’, with the price dramatically reduced to £19–19s–0d, while the Synchromatic continued at the same cost.

For the 1955 season the New Standard was marked up to £24–2s–0d, while the Synchromatic again remained at the same price, but presentations in The Motor Cycle and Motor Cycling editions of October 27th suggested an ambitious change was in the wind.

Various press releases described and presented a new Power Pak Moped wearing a motor taxation disc and registration number PAK 162, which seemed a little strange since the PAK series wasn’t even issued at this time.

Completing a search of the Bradford B vehicle files at Wakefield reveals that PAK 162 was allotted to an Austin motorcar at Whittly Hill Garage on 29th April 1958—so this serial appears to have been ‘mocked’ up on the Power Pak Moped model in 1955.

The timing of announcements at the end of October was in preparation for the Earls Court motor cycle show from 12th to 19th November (except Sunday 13th), 10:00am to 9:30pm, 3/- admission, children half price (except on the first Saturday).

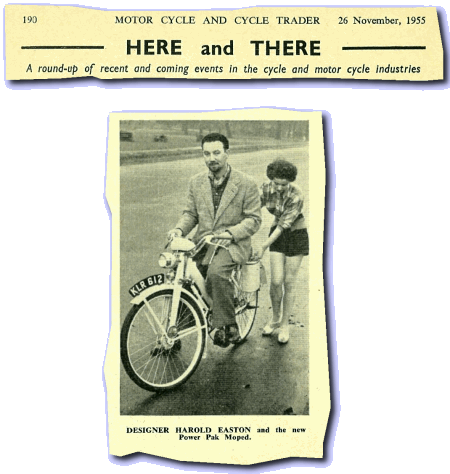

The new ‘Power Pak Moped’ exhibited on stand 19 at Earls Court, also seemingly wearing a motor tax disc, displayed London issued registration mark KLR 612, which rather oddly was a serial dating from 1949, so it’s suspected this might have been an earlier Power Pak registration that was ‘attached’ to the machine. All London registration records are listed as ‘destroyed’, so there’s no prospect of further researching this number by an archive search.

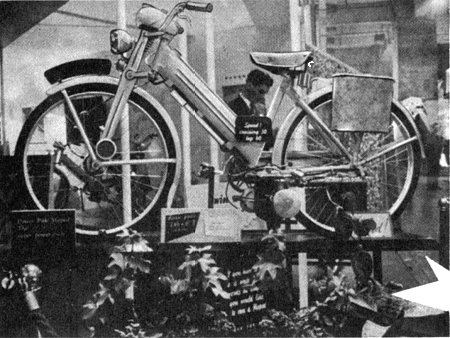

The display machine was equipped with further accessories, a pillion seat mounted on the rear carrier, and footrests bolted to the rear wheel spindle.

A price of £54–17s–0d was given for a Standard Moped, and £64–15s–0d against a De Luxe version, though quite what might be intended to comprise ‘included fittings’ or ‘further accessories’ wasn’t exactly clear.

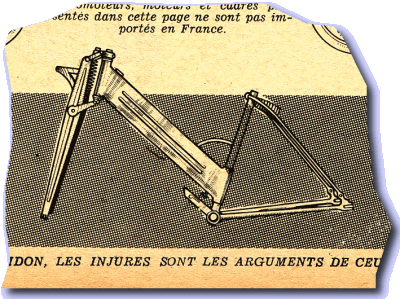

Casalini frame in Moto Revue

Described as a ‘streamlined facia unit’, the handlebar nacelle mounted an illuminated 40mph Smiths speedometer, ignition key-switch, and illuminated position switches for controlling the lights and traffic indicators.

The nacelle casing bore a striking similarity to the Power Pak cyclemotor petrol tank, and would appear to have comprised an adaptation of its pressed components.

The Power Pak Moped’s frame ‘carry handle’ is a very typical continental feature and rather gives the game away that the cycle chassis was unlikely to hail from any British manufacture … it wasn’t! The frame, assembled complete with the fork set was offered for sale as a proprietary kit by Italian manufacturer Casalini, and presented in a 1952 edition of Moto Revue.

Mystery has long surrounded quite what motor was actually represented by the little dark blob under the Power Pak Moped’s frame? This murky silhouette didn’t seem to match the established Power Pak cyclemotor, but historically available archive pictures were either vague or obscured, until the relatively recent reproduction of a previously unseen photograph in a foreign publication of a left hand side view of the Power Pak Moped confirmed the revelation of an Itom Tourist cyclemotor engine.

The Itom Tourist cyclemotor kit was listed in the UK from 1953 to 1961 and imported by Itom concessionaires: Adimar, 222 Brixton Road, London SW9—so there’s no obvious connection there.

The Power Pak Moped trafficator set appears to only have indicators at the back, mounted from the rear number plate bracket, either side of the stop/tail lamp unit. It would seem unlikely for this system to be powered from the engine magneto set, so presumably it operated from some dry cell battery. Since the lower panniers were featured as ‘detachable’, it would seem unlikely to locate any power supply there, so it is concluded this battery would be housed within the nacelle casing.

When the Power Pak Moped was announced in 1955, The Motor Cycle credited Sinclair Goddard of 162 Queensway, Bayswater, London W2, but its rival magazine Motor Cycling reported Power-Pak Engineering Co. Ltd, of Coventry, and further related ‘production of 1,000 machines a week is envisaged, thanks to the acquisition of a large and modern factory in Coventry’.

This Coventry address can be qualified from an earlier announcement in Motor Cycle and Cycle Trader edition 20th August 1955, that dealers should send small repairs (bearings, magneto & carburetter service etc.) to 162 Queensway, and larger jobs to Longford Works, Black Horse Road, Longford, Coventry, so this might seem to be the ‘new premises’ also referred to in pre-Earls Court Show Power Pak Moped advertisements.

No one really knows quite what or who Sinclair Goddard may have been, since this appears as no more than a faceless, shadowy name, connected with nothing but the cyclemotor and associated accessories. There appear no other references to this company, either before or after the cyclemotor, and no association with any other product.

News item in the ‘Trader’ gives the Coventry address

Just the tiniest clue about who may have been behind Power Pak can be found in Motor Cycle and Cycle Trader edition of 26th November 1955, presenting a picture of ‘Designer Harold Easton and the new Power Pak Moped’, and it’s notable that the young lady pictured with him also appeared in a number of the publicity pictures, wearing the same clothes, so we can probably conclude these shots were all taken on the same day.

You have to further dig back to a Motor Cycling edition of 14th Dec 1950, where an article on Power Pak reports in the text ‘Mr. H. Easton as Managing Director of the concern which now manufactures this little unit in London’.

It seemed that Mr Easton wore a few hats, and was fairly influential around the company…

Power Pak Moped at Earls Court

There are also period text entries referring to Bruno Fargion moving from Sinclair Goddard (Power-Pak) to Dunkley as engine designer of their two-speed, four-stroke motor series. Since the first 46cc Mercury Mercette version of the Dunkley engine also appeared at the very same Earls Court Show as the Power-Pak Moped, it might seem that Mr Fargion had probably gone to Dunkley before 1955.

It would therefore appear unlikely that Bruno Fargion had anything to do with the Power Pak Moped, so presumably his term with Sinclair Goddard must have concerned the Power-Pak cyclemotor engine. The timings of these movements are such to suggest that Bruno Fargion was probably responsible for the Power-Pak Synchromatic clutch model design, though whether his term went any further back to the original cyclemotor engine design is unclear at this time.

Power Pak Moped pictures variously appeared of what may appear to have been two prototype machines, both displaying tax discs, one wearing registration PAK 162, and a second showing serial KLR 612. That no pictures ever appeared showing both these bikes together, leads to the question as to whether there actually was any more than just the one model.

Power Pak Moped

We know that the later issued 1958 PAK number was ‘mocked’ up, and unlikely that the earlier issued 1949 KLR serial ever genuinely related to the moped, so one has to wonder if Mr Easton actually registered this prototype at all in 1955? It’s maybe more than circumstantial that the numbers KLR 612 and PAK 162 carry four common digits … possibly there was some ‘transposition’ of the adhesive letters and numbers, and there was only ever the single prototype model?

Subsequent to its Earls Court Show debut on 12th November 1955, the Power Pak Moped further appeared in 1956 trade listings, though only posted at a single model price of £56–12s–6d (presumably for the ‘Standard’), but there is no evidence that any production models were ever made or sold. There were no further references to the Power Pak Moped, though quite why the project failed has never been clear.

There wouldn’t seem to have been any sales cost issue, since the basic Power Pak Moped was competitively priced, with only the Norman Cyclemate and the Mobylette Standard being listed cheaper. It appears most likely that in attending the Earls Court Show in 1955, Mr Easton noted the increasing selection of newer geared and chain driven mopeds presented by other manufacturers, then probably appreciated limited prospects for his new roller direct-drive ‘Moped’, and that adding another such machine to the Power Pak cyclemotor range was going to be pretty pointless.

The Power Pak cyclemotors continued in 1956 trade listings, both with their prices increased: the New Standard to £28–7s–10d, and Synchromatic to £33–11s–0d.

Both variations of the cyclemotor continued to appear on trade listings up to and through the 1961 season, but failed to return for 1962.

The Itom Tourist cyclemotor also remained on trade listings up to the end of 1961.

Next: the second feature returns to business as usual, back to road tests … except this contains somewhat unusual content!

Actual motor wheel engines comprise a fairly small and select group of the cyclemotor genus, obviously the Cyclemaster, and BSA Winged Wheel, the Velmo, perhaps the Sinamec, maybe the stillborn TI Power Wheel concept model. You might even care to count the Honda P50 within this band, but there really don’t seem many ready examples where the hub is part of the motor kit … but an Italian motor wheel?

Even if we tell you that it’s 28cc, most people are probably still going to be stumped as to what this might be or when it was made?

There would seem no limitation to the distance that IceniCAM might travel to road test three of these Italian motor wheel cyclemotors in After the Gold Rush.

Seriously, to have gone any further—then we’d have to be leaving the planet!