Mercury enthusiasts now suggest there's a possibility that British built Mercury branded bicycles may have been produced a few years prior to World War 2, though any connection to the more familiar and later concern cannot be confirmed at this stage. Transfers & badges on these earlier cycles presented a different graphic from the post-war logo, but that may have little significance since manufacturers' badges often develop or change over time. All businesses have to start somewhere, and any pre-war Mercury would seem to have commenced from more informal beginnings, which is why practically nothing is known of its early origins.

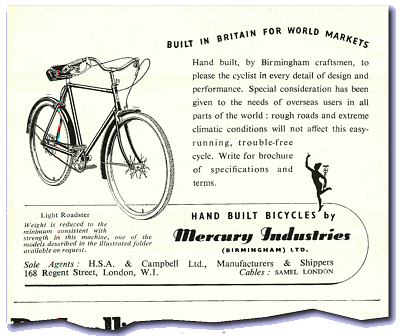

In December 1947, this Mercury advert

was aimed at export trade

It wasn't until after the war that the Mercury Cycle Company became formally registered and established at Stratford Road, Birmingham in September 1946, on an authorised capital of £3,000.

Mercury seemed to be one of those new businesses surfing the post-war wave to meteoric success, for within just two years they had secured significant North American export orders for bicycles; expanded into another factory at Dock Lane, Dudley, and were employing some 200 people.

Various Mercury cycles were also produced for military contracts, which were traditionally secured on the basis of very competitive tender bid pricing to a defined specification.

The first motorised products, launched in the early 1950s, were heavy duty cycle frames constructed for installation of the Cyclemaster motor wheel, and sold in gent's 'diamond', and lady's style 'open' chassis. 1953 listings added a Pillion frame with pad and footrests, and the Roundsman one hundredweight rated delivery frame with small front wheel and large carrier.

All four motorised cycle products continued up to 1955, when aspirations moved up another gear as the Motor Cycling edition of 10th November 1955 announced that Mercury was entering the lightweight motor cycle market with the four-stroke Mercette moped, and 49cc Hermes scooter.

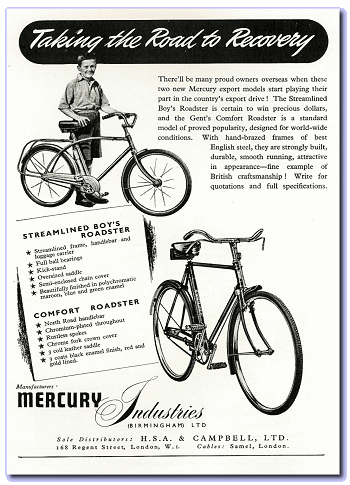

Another Mercury export advert,

October 1949

The Mercury sales office, service and spares departments relocated to new premises at Pool Street, Wolverhampton and adopted the title of Mercury Industries (Motorised Units) Ltd while cycle building and manufacturing services remained at the Dock Lane, Dudley site with finished motor scooter parts being shipped on to Wolverhampton for assembly at the Pool Street factory unit.

This revised business structure had obviously been planned sometime before the Earls Court Show introduction, since the Hermes scooter hubs were already pre-cast with "Mercury Industries" logo on their brake-plate face, which appear to have been manufactured by Grimeca in Italy, so this must have been prepared well ahead of the event!

After the Earls Court Show in 1955, the Mercette was recorded in manufacturer's lists from February 1956, but didn't actually start arriving in showrooms until July, so most of the first sales season had been missed. This delay must be credited to engine supply. The motor's only identification was the mark of "Mercury Industries" moulded into the dipstick cap, but its true origin would not become apparent to the motor cycling public until later...

Mercury turned up at the Earls Court Show in November 1956 with more fresh models: a 99cc Villiers 4F powered Dolphin scooter to replace the Hermes and the stand displayed a new Mercury Whippet 60 painted in Eggshell Light Blue, and powered by a similar 62cc four-stroke, kick-start version of the Mercette engine. This machine never progressed beyond the show model under the Mercury badge, but Hounslow perambulator manufacturer Dunkley announced their own Whippet "60" model in April 1957, and sold a number of these finished in the same colour, presumably using up the paint?

Dunkley built several kick-start variations on their little four-stroke engine theme, but the pedal-start Mercette motor was uniquely made for Mercury, and few parts were compatible with both types. Dunkley and Mercury seemed to share many common cycle parts on their machines: petrol tanks, front forks, and even paint. It was sometimes hard to tell where one company ended and the other began.

Also on Mercury's Stand 33 at the Earls Court show in 1956, the first Grey Streak motor cycle prototype model was presented as their new flagship. It differed in minor details from later production machines. The horn was conventionally mounted on the bottom fork yoke, but subsequently relocated to fit into the frame panel.

Glass's references indicate Mercury Dolphin scooter and Grey Streak motor cycle production commencing at March 1957, with Dolphin frame serialisation starting at D101 and Grey Streak at M101.

Our feature Grey Streak frame serial M342 was apparently produced during summer 1957, so let's have a look round our very pretty, new toy motor cycle.

Mercury's sales leaflet lists a Villiers 4F engine, but that doesn't appear to be what's fitted in our bike.

Generally the 4F engine can be recognised by being a kick-start version with cable gear selection operated by a trigger-change on the handlebars, and this may have been what Mercury were initially thinking of fitting when the literature was prepared. The 6F engine introduced in 1957 is more generally recognised by being a kick-start version with foot change gear selection and, despite what the sales leaflets declared, it was the 6F motor that was actually fitted to all the Grey Streaks produced.

The Villiers 6F engine will probably look fairly familiar to 2F autocycle owners since the top ends of both motors are practically identical. The 2F head has a decompresser to make the autocycle engine easier to spin over on the pedals, but the 6F motor cycle engine doesn't need this since the kick-start ratio spins the motor through compression easily enough.

Power is given as 2.8bhp @ 4,000rpm.

Though the dual-saddle looks rather as if it might have come from a bigger machine, this is the correct and original fitment, but it does look overly large and disproportionate to the rest of the bike. The extra wide portion of the rider's pad, however, does somewhat make up for its ungainly appearance in providing comfortable support for even the largest gentleman. A great many owners of small capacity Italian motor cycles of the period might have been quite envious of such sumptuous luxury!

Mercury's fitment of a dual seat and rear footrests to a 6F powered motor cycle was pretty ambitious, since every nearly other manufacturer fitting such engines to their lightweights supplied these machines with only a single saddle. Being 'generous' regarding the carrying capability of their machines was not unfamiliar ground to Mercury, they even offered an accessory pillion saddle and rear footrests for their 2bhp Dunkley four-stroke powered, 46cc Mercette moped!

Emphasised by their gold coach lines, the mudguards are trimmed with the most elegantly styled valances that finish these functional fittings as beautifully as a Venetian gondola.

The handlebars too are an exquisite artistic form. It's fairly unusual to find stem mounted handlebars on comparative lightweight motor cycles, most manufacturers opted for clamp mounted fittings, but it all makes sense when appreciating that Mercury were basically a cycle company, and stem mounted fittings were what they normally did.

From the stem, the handlebars circle forward in sweeping curves, then out, down, and back toward the rider. The stem is quite short, so there isn't enough tube to set the bars any higher, and then you appreciate that these are meant as a 'sports' bar. The bar set is a lovely piece of tube-work that riders can admire and enjoy every time they ride their machine.

There was a 'touring' alternative offered to the 'sports' bar, for the rider who might prefer a more upright posture.

Other fittings are more familiar to us - we've seen these forks before, on Mercury's Hermes scooter, and their Mercette moped. So they've transplanted the same very basic undamped, greased spring set onto their top-of-the-range lightweight motor cycle, which looks very elegant, but may be pushing the capability a little close to the limit!

A little bounce on the saddle is all it takes to appreciate that the rear suspension units have no damping effect in their action either. Mercury claimed the rear units were made by Girling, but that seems unlikely since the internals comprise only springs with rubber buffers. We've also seen these very units before, on the Dunkley Whippet, so the Hounslow pram manufacturer is more likely to be the real source.

OK, so we're probably not expecting the suspension to be anything exceptional, but the duplex frame is pretty impressive. It's unusual to see twin-down tube frames on many lightweight machines dating this far back, and maybe this warrants comparison with the traditional, brazed-lug excellence of Bown engineering, but the Mercury is a jig welded assembly.

The Mercury frame is a very different animal, undoubtedly very solidly constructed with heavy gauge metalwork (Mercury weren't noted for economy of materials), just as rigid as Bown's frame examples, but totally contrasting techniques.

Knowing there have been some 'criticisms' of Mercury's frame welding accuracy on occasions, we can't resist the temptation to glance down the axis from the back, and yes, the wheels are indeed out of line!

The Mercury duplex frame may look the business, but they didn't seem to have mastered the distortion stresses created by electric jig welding - it's no comparable quality to the pinnacle of Bown's precision.

A steel fabrication fills the frame behind the engine. It looks very nice, and pleasantly blends the general ambiance, but appears a particularly intensive engineering approach in comparison to similar modules by mass-production manufacturers. Streak's frame-box forms an elegantly styled panel assembly that carries the horn on one side, and a domed lid to a small toolbox cartridge on the other.

It's interesting that the rims appear in painted finish to match the frame. The restorer reports that during preparation, the painted rims were stripped back to bare metal, and presented no evidence that they were ever chromed, so were returned to a painted finish.

The brochure quotes rims as chromium finish with 2.25 × 19 tyres, and other Grey Streak examples have certainly been confirmed with chrome rims, so it appears possible that Mercury may have employed both options.

Mercury might have been a little 'flexible' on some other of their specifications, their interpretation of "Mercury Grey" for the Streak appearing to be another example. While our test machine was restored in a close match to the light blue/grey original paint, another machine owner restored his example in another close match to the original beige that frame M173 was finished in!

The British Hub Co. four-inch full width hubs are another somewhat economy fitment carried over from the Mercury Dolphin scooter and will probably be quite familiar to riders of Norman Nippy, Hercules Corvette, Phillips Panda and Gadabout mopeds. The operative word here being 'moped', which rather suggests the hubs and brakes are likely to be pushed to their limit in employment upon a motor cycle of twice the capacity!

Later 6F engines mounted the later Villiers S12 carburettor, but earlier versions officially fitted the Junior type carburettor with a strangler choke filter. For the 4F/6F this was technically referenced as a .6/0 carburettor having an unthreaded filter spigot, and fitting a J120 jet block with 2½ taper needle. The autocycle Junior carb had a threaded filter spigot, slotted for a shutter choke, with J8 jet block and the same needle.

The two-gallon petrol tank has a very deep centre ridge, but a 2½" clearance between it and the top frame tube does make you wonder if the tank pressing might be an adaptation from something else? While the resultant gap at the back is blanked over by the seat, the gaping throat at the front of the tank looks like the entrance to a small cave, with the sheathes of the wiring loom disappearing into the blackness within.

A balance pipe connects the two sides of the tank between the centre ridge. There are pros and cons with this system; though it allows the fuel to crossover the separated sides OK, it does mean you'll have to drain the tank if you want to take it off.

Fuel turns on by a simple off/on lever tap at the left hand side, with no reserve.

There's a switch on top of the 4½" Miller headlamp, but this only appears to turn the lights on when switched to the right, and is not wired up to earth out the ignition in left position like the Mercette moped. The left switch position may alternatively have been used for a dry cell battery 'pilot' set, but now long gone from legal night parking requirements, none of these obsolete old systems ever seem operable today. Mercury literature doesn't really seem to explain the switch function, so we're left wondering how you might be meant to stop a motor if the engine is set to tick over? The Mercury Dolphin scooter with 4F engine was described as having an 'engine cut-out button on the handlebar'.

There's another switch on the left handlebar just for beam/dip and horn, so we presume the Streak to be just kick and go.

Taking the bike off its centre stand gives a most unfortunate early impression. The stand goes forward way over-centre, and requires the bike physically lifting 4½ inches to clear maximum point, whereupon it usually flicks smartly back on the spring, leaving you holding up the frame. Manhandling the 143 pound bike back on to its rest is a similarly ungainly operation and we've already decided we hate this stand with a passion.

Mercury's brochure described their stand as "Specially strengthened, Quick release, foot operated", leaving us wondering if it was originally like this, or whether something has gone bad over the decades?

Closing the strangler choke on the carb, just a couple of jabs on the kick-start has the engine fired up, then open the shutter almost straight away and clear the motor with a few light revs.

There's a noticeable top-end noise coming from the motor ... rings, piston rattle, maybe small-end? Our workshops would be keen to take the motor apart and sort that out, but the owner says it's just been rebuilt by ******** ********, so diplomatically moving right along...

The Mercury two-stroke megaphone produces an interesting tone, which the sales leaflet describes as "Scientifically developed sports model racing type, with a distinctive but unobtrusive note". Well, it does seem to smooth out the bark, but is still pretty loud.

The clutch lever has a pleasantly easy action, while the gear-change proves nice and light on the shift and locates its ratios with a positive click. One up for first, one down for second (top), with neutral between.

We soon settle down to steady cruising at 33mph, which is most comfortable with no vibration and the engine happily running at a nice steady pace ... until just a mile and a half out, the motor suddenly dies as if the ignition has just switched off. We coast to the side, take out the hot spark plug (ouch, ouch!) and, sure enough, a great big whisker bridging the contacts. Just wipe the whisker away with a piece of rag between the electrodes, and off we go again. Vibrations start creeping in around 35mph, and we push on to a best of 37mph in a crouch position, on a flat run, in crosswind conditions, with the motor pulling consistently under two-stroke running.

As we shut down for the junction at the end of the flat run, the motor starts coughing again with another plug whisker obviously forming, which seemingly clears with a bit of throttle jiggling, but returns with a vengeance just another mile up the road as the Streak dies again shortly before the downhill run section.

More tedious de-whiskering beside the road, hot plug (ouch, ouch, again!), then back down the road to get a run-up to speed for the downhill blast of 39mph with revs now being restricted as the firing breaks into a limiting wall of four-stroking. If the constantly whiskering spark plug wasn't enough to diagnose overly rich carburetion, then the staccato four-stroke running off load downhill would probably convince that the mixture wasn't tuned in.

Just a bit of weakening off by turning the needle down in the slide would probably resolve the whiskering problem and improve performance, so we're pretty sure that a Streak in correct tune shouldn't have much trouble in cracking the 40mph barrier.

The following uphill run never fell below 25mph, easily staying in top gear all the way up, as the motor typically returned to clear two-stroke running under load, to power up the incline.

Now with a hot engine, we paced the maximum in first up to 21mph (revving out), but under normal usage a rider would expect to change up around 12 to 15mph.

Brakes ... what brakes? The rear brake pedal is purely psychological! It's very hard underfoot, and just feels as if it's hit a physical stop before anything happens! You could possibly believe it even had metal pads on the shoes! Pressing the pedal sometimes produced a clonk, or whirring rattles, but absolutely no braking at all. Completely useless!

The front brake lever was soft, spongy, and largely ineffectual. By pulling the lever up to the bar you could slightly improve the gradual rate at which the bike might be slowed down - and this was the better of the two!

The lights might have been working on the outward leg, since the pace bike rider reported the rear light was on, though this may have been the brake lamp, since the light switch appeared to be turned off. The back light apparently went out about halfway round the course, and by the time we returned to base, there were no lights at all and only the horn worked. These old electrical systems are such a joy!

Limited performance from the Villiers 6F motor didn't overwhelm the Mercury chassis, and overall handling of the Streak wasn't as bad as expected considering the undamped suspension and questionable wheel alignment. A number of disappointing aspects about our Streak failed to match up to its attractive looks, but there were occasional moments on the test run ... tucked down into a headwind, the engine pulling hard in proper two-stroke firing, a flat blare from the megaphone drifting across the fields, weaving through a light sequence of bends with the pace bike in pursuit.

Just rare glimpses of what a beautiful little bike the Mercury Grey Streak could become if anybody could sort one out!

By October 1957, Dolphin frame serials had reached D2080, but the Grey Streak was lagging way behind, only M462, just 18% of the numbers of the scooter. Market money certainly didn't look to be in motor cycles at this time!

Mercette frame serials ran from 100 to 765 by October 1957, by which time Mercury were getting into trouble.

By the next month, the reduced workforce was on short time, and what resource the factory had in the 'motorised division' was probably being concentrated toward the new Pippin Scooter.

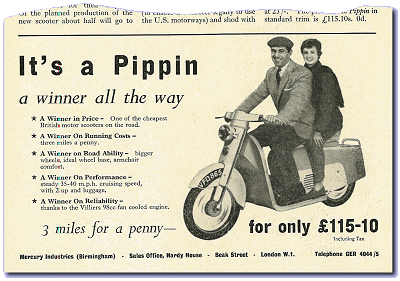

"After having successfully completed five months testing at a Midlands research laboratory", the Pippin was presented in January 1958 at a champagne launch party in the company's office at Beak Street in London.

Interviewed by the Express & Star motoring correspondent for their edition of 19th January 1958, Mr John Abrahamson, Managing Director, announced plans to produce 15,000 Pippins in 1958, half of this being planned for export, and starting with an initial USA export order of 2,000 machines valued at $250,000, then concluded by declaring the first of this batch order to be leaving the country in the middle of the week.

It looked as if success could have been snatched from the jaws of defeat in the eleventh hour ... but events shortly proved more like snatching disaster from the jaws of victory!

The Pippin Scooter proved to be the final epitaph; styled like a bad Sci-Fi 'B' movie, few found their way out of the factory as the company plunged into meltdown.

The Palace of Cards collapsed on March 1st, 1958 and all production at Mercury ceased on this date.

Considering Mercury's ballistic success over its first 10 years of business, it may appear something of a puzzle how fortunes of the company could so rapidly change?

There are several factors that contributed to this downfall, and it was particularly unfortunate that these happened to come together at much the same time.

Mercury's success was primarily built upon cycle export orders, but towards the mid-1950s, contracts began to dry up as cheaper overseas manufacturers began to take over these colonial orders.

As the primary income source from cycle sales started to shrink, Mercury was increasingly betting its future on motorised products, none of which were to prove particularly successful.

Managing director, Mr Harold S John Abrahamson was no stranger to colourful and optimistic exaggeration, who following the 1955 Earls Court Show claimed to have "secured valuable home and export orders for the Hermes scooter to a total of about £220,000" - obviously he had a different way of calculating his mathematics than we do!

Unappealing, overweight and underpowered, the 50cc Hermes scooter struggled to find buyers, and reportedly created warranty issues with recoil starter failures of its Ilo G50 motor. Frame records indicate only 1,100 Hermes being built, so the model certainly never generated significant income. Even the list price of £75-10s only presents a total asset of £80,000, and Mercury was seeking to claim a quarter of this figure back (£20,000) in 'damages' from Ilo. This recovery claim representing £18 per unit would probably have equated to the full cost of the engine in the first place - probably a little unrealistic!

The buying public never did take to the Mercette moped, and who could blame them? It was difficult to use, impractical, unreliable, and developed a poor mechanical reputation for dropping its valve seats out of the cylinder head.

There is little evidence to suggest any more Mercettes were completed beyond the 665 October figure. With 256 Mercette engines listed in the bankruptcy sale and allowing for a balance of 79 more motors given to warranty, suggests the probability of a 1,000 batch being originally purchased from Dunkley, and underlines what a disastrous failure the Mercette moped was.

The cumbersome and ugly Dolphin scooter surprisingly fared rather better, clearing some 2,000 units to the trade within eight months, though dealer sales to the public were actually much slower, with many examples not being registered until after Mercury's demise.

Considering it was such an attractive bike, sales of the Grey Streak must have been particularly disappointing, but motor cycle sales from all manufacturers across Europe were falling away in the late 1950s - it was just a sign of the time, and a new age for the motor car.

Mercury's manufacturing, assembly, sales and business offices were based on several scattered sites, which obviously didn't help its cost efficiency in transporting materials and operating between locations.

The marketing department seemed to continue with lavish promotions in apparent disregard of the financial position, so there almost appears a certain inevitability to the disaster when the position is analysed.

By the later stages, everything was being gambled on success of the new Pippin scooter to save the company, though the positive-spin sales orders and marketing projections seemed little more than a desperate last attempt to keep the show on the road - but the clear reality was that Mercury was failing to pay its bills.

Mercury's meltdown was as dramatic as its ascendancy.

The gravity of the situation was quickly revealed in local newspaper reports.

On Sunday 15th March 1958 The Dudley Herald reported "the Birmingham Company was calling a meeting of its creditors next Thursday, and a decision would be taken as to whether the firm should be voluntarily wound up ... now there are only a dozen or so people left on the pay roll".

Following the meeting of creditors on the Thursday 20th March, Mercury Industries entered into voluntary liquidation

The following day's headline reported:

A loss of £164,431 suffered in 18 months by a Black Country firm of cycle and motor scooter manufacturers was described by a creditor as "Fantastic", at a meeting of creditors in Birmingham yesterday.

The firm, Mercury Industries (Birmingham) Ltd. which has premises at Dudley and Wolverhampton has gone into voluntary liquidation.

The statement of account shows an estimated deficiency as regards creditors - subject to cost realisation - of £87,468: and an estimated deficiency, as regards contributories of £123,368.

Two months ago, the firm started making a new scooter, known as the Pippin.

The founder-director, Mr. Harold S John Abrahamson, told the meeting that large sums had been spent developing this scooter, and it would be in the interests of creditors if some scheme can be formed to take advantage of the considerable development work on the scooter, for which there are now large orders worth £120,000 on the books".

A creditor said to Mr Abrahamson: "You were being pressed for money, yet you carried on with this development work. Should not you have done something before?"

Mr Abrahamson replied: "To show the confidence we had in the company we ourselves guaranteed a loan of £39,000 - it was a personal guarantee by me."

A London accountant, Mr. H.W.Pitt who presided at the meeting, said there was a considerable amount of investigation to be made into the company: and possibly into the affairs of companies associated with it.

He was not yet in a position to say, however, just what would happen to those associated companies, H.S.A. and Campbell Ltd., and Mercury Cycle (Sales) Ltd.

The company was formed in September, 1946, with an authorised capital of £3,000. This capital increased until it was £57,000 in 1957. The present capital was £35,900.

In the 18 months to September, 1953, there was a turnover of £281,231, a gross profit of £45,510, directors remunerations nil, and net profit, subject to tax, of £918.

In the year ended September, 1956, the turnover was £517,242, the gross profit £75,911, directors' fees £1,085, and net profits £10,784.

Mr. Pitt said: "There are no audited accounts subsequent to September 3, 1956, but draft figures for the period October, 1956, to March, 1958, show a turnover of £731,757, directors remuneration £4,370, and a net loss of £164,431."

During last autumn, he said, winter bicycle trade sales were seriously affected by the seasonal drop and trade recession in North America.

Mr. Abrahamson was ill in hospital between January and March, 1957, but he then visited the United States for two months, seeking business. He had been able to attend the company's premises on about ten occasions since.

There was a claim for £20,000 for damages against the German manufacturers of an engine which had proved unsatisfactory.

There were, said Mr. Pitt, reasonable grounds for believing that claim might prove successful.

Two liquidators were appointed - Mr. Pitt and Mr. R.F. Bendall - and a committee of inspection was formed.

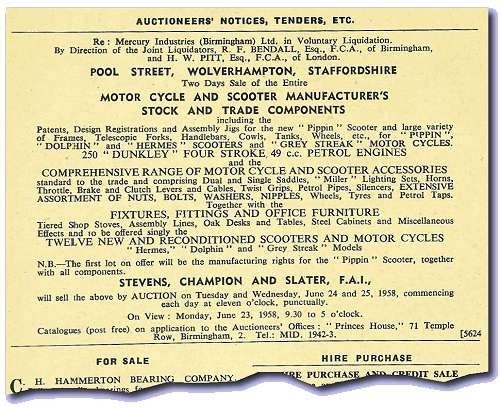

The auction of Mercury's assets was originally

scheduled for 24 & 25 June 1958 but

postponed until September

The local paper reported the first part of Mercury's liquidation sale on 3rd September 1958, under the headline:

With only few exceptions all the motor cycle and scooter components sold by auction today at Mercury Works, Dudley went for scrap.

The sale by Stevens, Champion and Slater was by direction of the liquidators of Mercury Industries (Birmingham) Ltd. a company in voluntary liquidation.

Principal buyer in the first two hours of the sale was Smethwick scrap merchant Jesse Beard. He told the Express and Star "Most of it will go straight into the baling press".

During the sale of the first 120 lots the name of "Beard" as the buyer became so frequent that towards the end the auctioneer exclaimed "poor Mercury" and started to name Mr. Beard automatically after reading out the lot description, adding sadly that Mr. Beard's price was rarely over 25s.

The first lot, six "Pippin" scooter frames set the pattern. They were worth, said the auctioneer, £35. They sold to Mr. Beard for 25s. The Pippin was the last model introduced by Mercury Industries, with a champagne party in a fashionable London Square (Mercury Industries also kept a London office at Beak Street), before it went into liquidation.

Later Mr Beard was buying such lots as 100 exhaust pipes (selling at 3s-6d each), for 12s-6d: 40 petrol tanks at 10s-3d each, and almost finally, 400 front and rear mudguards for the Grey Streak for 10s.

It was expected there would be some more serious demand for 256 Dunkley 49cc four-stroke petrol engines. When the auctioneer could get nothing more than £4-10s each (there was in fact no bid at all) they were unsold.

Immediately afterwards a buyer paid £6-10 and £7-10s for two 98cc Villiers 4F two-stroke engines.

The sale continued today with several hundred thousand cycle components, together with a large quantity of unused cycle and motor cycle tyres.

Tomorrow the sale will include more cycle parts and the company's tools and manufacturing equipment.

The Mercury Register records only four surviving examples of the Grey Streak, the highest frame serial being M562 and leading to the conclusion that only some 500 of these motor cycles were ever completed.

Next - We seem to experience some strange feeling of déjà vu about our next main feature?

The story starts with a request to test the smallest capacity motorised vehicle that Honda ever made. That might seem simple enough, except there don't appear to be any known examples in the UK. OK, so we might have to be prepared to travel abroad, maybe Europe, well that's not so bad.

So who do we know with a really nice example of one of these ... at Pongakawa ... What? You can't be serious! All the way to New Zealand again?

Faced with the prospect of a ridiculous 26,000-mile round-the-world trip to test this 24cc cyclemotor, People Power had better be worth it!

[Text and photos © 2012 M Daniels. Period documents from IceniCAM Information Service.]

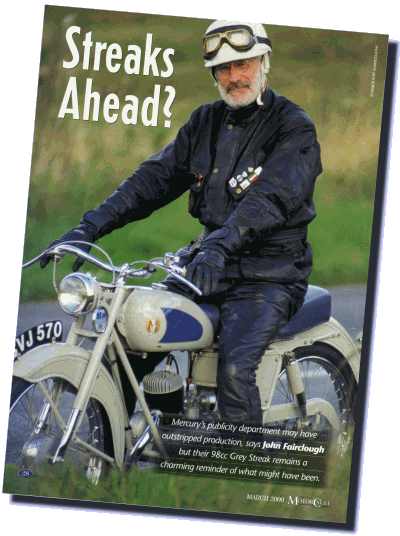

John Fairclough's Grey Streak was

featured in The Classic Motor Cycle

in March 2000

Our Mercury Grey Streak Meltdown article had certainly been long in the planning.

The original intention had been to develop the article based on another Streak, M173, restored by John Fairclough but, for various reasons, the logistics never seemed to come together, the bike was sold on, and now stands on display at the Black Country Museum.

While going round the VMCC Founders Day event in July 2011, we were most surprised to spot another Grey Streak on the British Two-stroke Club stand, so we stopped to have a chat with the owner, Charles Sylvester.

The bike wasn't one recorded on the Mercury register at that time but, when Charles showed us pre-restoration pictures and told the story of where it came from, we then realised it was one we had previously been aware of, though not actually tracked down. The last time the Mercury Register spotted pictures of the bike was in decrepit condition when it came up for sale on an internet auction site. CS bought it from Rochdale and spent some time on restoration, until M 342 finally emerged on show.

We took details of this new Streak, making just four recorded examples on the Mercury Register. They really are a very rare machine but Charles had many bikes and other on-going projects, so the Streak was being earmarked for selling on to make way for other restorations.

The offer to list it up for sale on IceniCAM Market was accepted and, knowing that we occasionally license out articles for publication in the BTSC magazine The Independent, Chas kindly offered the Streak for roadtest and photoshoot. Well, we're certainly not going to risk missing another opportunity to test one of the rarest light motor cycles in the world, so we pretty much dropped everything else and arranged to collect the bike for process within the next couple of weeks.

It was a six-hour round trip to collect the bike from up near Leicester, and burned off £40 of diesel fuel in the process, but IceniCAM had secured the Streak for the following week.

Only Streak's disproportionate saddle aroused some disparaging remarks, otherwise everybody was struck by how pretty the bike looked. The road test proved a little disappointing though, since the Streak had been freshly assembled, but never ridden or sorted out - consequently it was riddled with unsorted glitches.

Our workshops addressed the steering head bearing adjustment (essential for the road test), but there really wasn't time to sort out anything much more before the bike was due to return, and we only had use of the trade plates booked over the one weekend. There was nothing for it but to present this pretty looking bike as it really was, warts and all!

The restoration was certainly a nice cosmetic job but, if a bike is to be anything more than just for show, then it needs to be de-bugged and made to work properly. Our beautiful Mercury was between these worlds and suffered on test as a result, but there were moments on the run when it went well, and you got a brief glimpse of its potential to be a really fabulous little machine.

We've produced articles on Mercury before, The Lost World on the Mercette in April 2002, and Olympian Chariot on the Hermes in May 2006, so there's always a pressure to come up with some new material for any subsequent feature. Two previous articles = twice the pressure, so we really dug deep for the fine detail this time.

Dunkley and Mercury marque specialist Noel Loxley was of great assistance in providing obscure archive files.

Presentation of the article also required a different angle to avoid too much repetition of previously published material (which some authors seem rather prone to do), so there was a particular focus on details of Mercury's meltdown and final collapse to enable a fresh slant on the story.

Costs of our journey back to return the bike were offset by delivering an early Honda C100 Cub along the way, so final production cost for the Streak article was held at £40.

A sponsorship from Chris Marshall in Bermuda had been sitting in credit lists for some time, which we were planning to attach to a Mobylette AV78 article that hasn't materialised yet, so Chris scores the Grey Streak instead.