It’s not hard to follow some reasoning that leads to the creation of micro machines…

Design brief: a motor vehicle that can be readily stowed in the back of car and be functional for short distance transport.

Anyone can perceive the appeal of such a device, so it’s just a matter of making an attractive machine that would catch the eye and open the wallet.

There are conclusions that would probably narrow down what such a vehicle might be at any point in time—obviously as light and small as possible, and probably collapsible, to reduce to a compact size.

Presuming this time might be the 1970s, and the smallest practical transport would be 50cc, so we’ve logically arrived at a small folding moped, then you’ve got to accommodate fashionable styling of the day if you want to sell the product.

The X1 was originally produced for the 1971 Paris Motor Show but, as is often the case in the world of marketing, this was not really any idea that hadn’t sort of been done before and it’s easy to perceive similarities to the early 1950s’ Brockhouse Corgi, possibly the Piatti scooter a decade later, and maybe toward the later 1960s’ Raleigh Wisp. These machines are all probably considered small icons of their own times, and styling of the X1 was surely as iconic for this moment as its predecessors were in their own generations.

Motobécane introduced the X1 into the UK in May 1973, and its striking modern looks certainly created a sensational impression at the time. This little bike just screams classic 1970s’ design, and it’s really not hard to see why it generates almost cult appeal to followers of the micro-bike fashion.

Weight is critical for X1 since its purpose relies on being lifted into the back of a car by means of a suitcase style handle along the top frame tube.

All fittings are purposefully kept as simple as they can possibly be. The rigid frame and forks minimise on metalwork, the 2.50 × 9 tyres on cast alloy wheels are about as small as they could possibly be, with lightweight plastic mouldings employed for the front mudguard, body shell halves, and die-cut poly sheet for the internal rear mudguard.

The handlebars lock into position by a cam-lever on the steering head, then a spring-loaded pin runs in a groove to keep the handlebars central to the stem. Draw the knob to fold down the 16-inch high handlebars, and they hinge right down from a 39-inch riding position to straddle the main body shell.

Purpose of the peculiar pull-back bar form becomes appreciably more obvious in folded mode, as any conventional handlebar arrangement would stick out and compromise stowage ability.

Saddle height is locked by a screw clamp on the seat stem, then telescope the stem down and into the frame. From 35 inches at maximum extension, the seat will close down to a highest point of just 24 inches.

For loading, the 35-inch wheelbase results in just 51 inches nose to tail length, and raising the total deadweight of 77lb, the bike remains in perfect balance on the lifting handle.

Despite their small size, the 70mm diameter hubs offer tremendous stopping ability in the tiny 9-inch wheels, so much so that the front brake needs to include an anti-lock feature as the cable pressure is regulated by a compression spring acting on the sheath.

A Motobécane Cady motor lies at X1’s beating heart—an interesting choice of engine offering miserable performance with wretched serviceability issues to the ignition set, and presumably selected on the basis that the model was probably never intended for speed.

The rotary throttle control is most unusual for Motobécane, since pretty much every other moped model they produce employs a cursor throttle. The rotary throttle, and in fact all the rest of the handlebar furniture (brake levers and even handle grips) are further unique in mounting on to ⅝-inch (16mm) bars! For some unfathomable reason, the X1 handlebars taper from a conventional ⅞-inch (22mm) from halfway up the stems, to this tiny diameter at their top!

There seems no logical reason for this at all, so can only be put down to some inexplicable French styling fetish—it’s certainly going to present major problems to anyone looking for spare parts!

The petrol tap is tucked down by the engine behind the left-hand side panel, where it’s fairly difficult to access and operate the lever: off/on/reserve.

A thumb lever operates the choke by cable from the left-hand handlebar. Turn the throttle twistgrip forward to decompress and, in deference to the dainty little stand that’s obviously not going to recommend sitting on the bike and furiously winding it up, we considerately opt for the flying start technique and pedal down the road.

Whether down to the pedal drive ratio or some anomaly in the starter clutch, it proves pretty hard work to get the motor turning enough to fire it up, but we persist and the Cady putters quietly into life. Further thumbing the choke briefly until the engine runs clear on its own, we open the throttle to pull away…

Not quite what you might ordinarily describe as acceleration…

To be honest, it’s pretty pathetic, and you really do need to give a little pedal assistance or you might be at the kerb all day! The clutch locking shoes seem to engage somewhat prematurely, and the feeble Cady motor just labours in vain at low revs.

Pedal assistance also needs to be something for cautious consideration, since the pedal arc takes them fairly close to the ground, there’s not much free clearance, so you might be in danger of hitting your feet—that can really hurt, and cause a further painful spill.

Once you’ve got underway, there’s a brief illusionary moment where you optimistically think ‘maybe it’s picking up now’—no it isn’t! That’s all there is!

Along the flat and according to wind conditions, the Cady will generally grovel up to 15–18mph, maybe even touch 19 or 20 with a decent tailwind on a good day. Even gentle gradients just seem too much effort for the indolent motor, which readily fades down to 13mph in a general performance that seems more comparable with ancient and primitive cyclemotors of the 1950s.

Turning back the way we came, the same light downhill run gave our best paced reading of 22mph.

From the riding position, and looking down on the retro ’70s missile bodywork may conjure some rocket jockey image, but the reality of Cady’s engine performance is a sobering illusion—not for nothing is the white X1 more commonly known as ‘The Albino Slug’.

Anyone getting on an X1 is generally going to be thinking there’s something rather wrong with its motor, but no, everything is normal; that’s just how the Cady engine is. The ‘blank’ right hand crankcase cover pretty much gives away that the motor has an overhung crank. The drive journal on the left-hand side runs a smaller version of the usual Dimoby automatic clutch, with inboard pulley and belt guarded by a snap-fit plastic cover. The mag-set, however, is mounted between drive pulley and the engine, which means you have to remove the clutch in order to service the contact points—and rather tends to be a bit of a service issue!

The exhaust pipe exits to the right-hand side front of the cylinder, while the inlet manifold enters to left-hand side front of the cylinder, with the pipe snaking its way back around the cylinder, where a 10mm Gurtner carb mounts at the back right-hand side. An 11-inch (270mm) long intake manifold on a two-stroke is obviously not going to help its performance, when nearly half of the induction volume of each stroke is lost in the inlet manifold.

The engine configuration is generally summed up as ‘why on Earth did they do that?’

The earliest Cady versions were designated M1 and introduced by Motobécane in 1965 as their most basic machine to compete with the low cost VéloSoleX.

Inside the barrel, the inlet is piston-ported, and there are two conventional transfer ports at the sides of the cylinder, with an extra ‘boost’ port that feeds through the piston at the back of the cylinder. The exhaust and transfer ports are all pretty small, so effectively prevent the motor from developing any high revs.

The Cady engine went through a number of evolutions, its prototype having a conventional crank with two bearings.

The first production models had an overhung crank and a single bearing with two seals and packed with special, petrol-proof grease, about which there are dire warnings in the manuals:

Firstly, not to use a piston stop when removing the clutch.

Secondly, only to replace the bearing with one supplied by Motobécane, because ones from other suppliers won’t have the right grease in them. This system was used to July 1967.

After July 1967 (maybe quite a while after, since there was a strike at the factory), a needle roller was fitted in addition to the ball race. From September 1970, the outer sleeve of the needle roller was cast into the crankcase, so they then had to supply the needle bearings in five different sizes at 2 micron increments.

A later version of the Cady—the M3—had a proper ‘super isodyne’ two-bearing crank but the M1 and X1 models continued with the overhung crank. There doesn’t appear to be much ready reference about power output, but both M1 and X1 quoted a maximum design speed of 33km/h (about 20mph).

Motobécane’s idea of producing a ‘portable moped’ pre-dated the X1. The PliCady M1P was launched in 1966. This could be dismantled by removing the forks, handlebars and seat. Its brakes were arranged the ‘wrong way round’: the rear being controlled by the right-hand lever so the twist-grip and lever assembly could be taken off the bars and stayed with the frame to save having to disconnect any cables when ‘folding’ the bike.

The Cady was first imported to the UK in November 1966.

X1 lighting equipment is very simple and basic: a Soubitez single-filament headlamp mounted between the handlebars, and ULO taillight, both with lightweight plastic housings. Operated by a single switch on the top of the headlamp, the 6 Volt AC lights prove quite adequate for the 20mph performance.

Operated by a tiny metal button, delicately styled into the left-hand side brake lever bracket, the electric horn produces a raspy buzzy rattle, which is adequate to satisfy transport testing requirements.

The X1 was joined by the X7 model from January 1974, which was installed with the more conventional 2bhp M-series motor, and offered the potential of more typical moped performance.

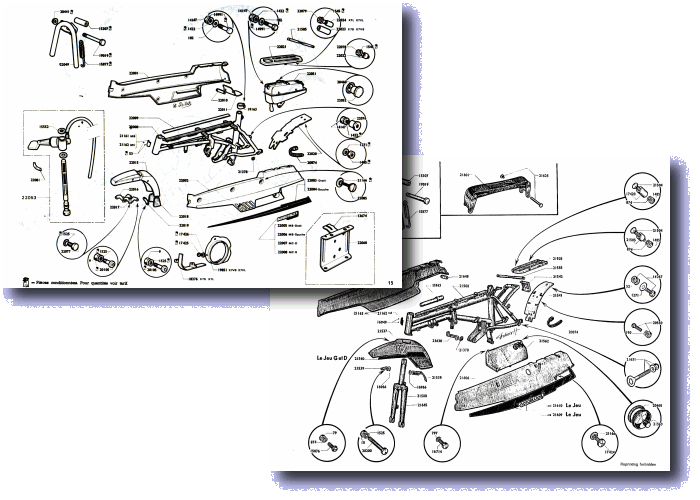

It’s commonly presumed that the X1 and X7 models are the same machine just fitted with different engines, but not so. Stand them side by side and the X7 dwarfs the X1. Though similarly styled, X7 has a different frame, telescopic forks, bigger 10-inch wheels, all the panel mouldings are larger—there’s actually no component commonality at all.

Comparison of X7 (top left) and X1 (bottom right) components

Time however, was very brief for both machines. Their moment quickly passed, and both were discontinued in March 1976.

Parts are a big problem for surviving examples of X1 machines today, since virtually everything on them was unique to the model and practically nothing else will fit. Tyres are probably the single most critical item to keeping these vehicles roadworthy, since no manufacturer currently seems to list any 9-inch sizes.

Next—The oddball third feature seems to be heading into some bizarre, post-nuclear, apocalyptic future with this speed crazed warrior from the Anglian wastelands. Has the humble Puch that everyone knows and loves, become irradiated into some twisted demonic mutation? The innocuous and faithful Maxi may never be seen in the same light again, after—Mad Max!

[Text and photos © 2012 M Daniels. Period documents from IceniCAM Information Service.]

The Motobécane X1 feature came about as Monkey bike and Micro-machine fan Simon Taylor brought his X1 into our workshops for complete mechanical restoration up to MoT standard, which, knowing the complete lack of availability of essential parts for these machines, was going to prove quite a challenge.

The ‘S’ suffix plate (1978), indicated the bike had been registered 2 years after imports of the model were discontinued in the UK, rather suggesting the X1 hadn’t actually been selling very well in its time.

Probably like a lot of these micro-machines, the X1 looked as if it’d had very little actual use, since the tiny rear sprocket showed barely any sign of wear. It looked as if the bike had been abandoned because of a broken throttle cable and handlebar cam-lock lever. Components detached from the bike became misplaced when the twistgrip was dissembled and, just for want of a throttle cable … the bike was lost!

Over a year of trawling the internet by Simon had produced no result, so there was going to have to be another solution if the bike was to be recovered.

The missing throttle components and broken handlebar cam-lock lever were resolved in the only practical way possible, by machining up new replacements. Other general repairs and improvisations were not really any problem—until it came to replacing the 2.50×9 tyres. No 9-inch tyre sizes are now listed by any manufacturer—basically, they’re extinct!

It just happened, however, that there were two 4-ply new/old stock Ceat 2.75×9 tyres listed in the Chainmail stock but, because of the compactness of X1’s close design, even this slight increase in diameter and width proved a problem, requiring modification to the rear frame to allow the back wheel to fit. Up front, the forks also needed to be splayed to accommodate the width increase, with appropriate spacers on the axle adapted with special inserts to set the wheel down the fork by 5mm, which generated clearance for the diameter increase.

All went well, and the modifications enabled the installation of a pair of far better quality tyres than the flimsy Hutchinson originals, which had all the structural capability of a plastic bag!

As work on the bike completed in June 2011, and it checked through MoT for return to its owner, we thought we might whiz it through a quick road test and photoshoot for an article since we’d not had opportunity to cover one of these before, and the bike had now become a fairly reasonable and roadworthy example.

All-in cost of recovering the X1 knocked on £400, but since Simon originally acquired the tiny bike for a mere token, he reckoned the investment was worth it for a completed and roadworthy machine—and you certainly don’t see many of these in use today, so it’s probably perceived as a fairly unusual example now.

X1’s biggest let-down has to be the miserable Cady engine, which pathetic output restricted its performance to the 20mph category. This may be considered adequate as a micro-compact for ‘camper site’ use, but not really effective as a proper moped since it wholly lacked the capability to keep up with general 30mph town traffic pace.

X1’s performance would prove a practical limitation to its sales capability, which Motobécane addressed to some degree in the later X7 version, installed with a 2bhp M-series motor. The X-series, however, proved more novelty than longevity and, as is the way with these flighty things, its customers moved on to new novelties. After just 5 years’ listing, the models were discontinued in 1976.

Rather like Marmite, whether you love or hate these machines, the X-series concept and styling was always iconic. The little bikes have achieved almost a cult status and still appeal to many people, who will appreciate and collect them—though very few are probably likely to be seen in highway use today.

Folding the X1

Owner Simon Taylor delivered and collected the bike, all pics were digital, so our production cost of the ‘Micro Solution’ article was effectively nothing, though the workshop certainly clocked up the hours to restore the bike to functional order.

As we completed the test feature, Simon contributed a token donation to bring the article on to publication.