Following on from our Stingers feature, this second chapter on Garelli almost seems to take us back to the start again, except it recommences with a different story from an earlier beginning...

This thread opens in 1832, at the birth of Antonio Agrati, who grows to become a skilled blacksmith in the small town of Brianza, Cortenouva di Monticello, within the province of Como, Italy.

In 1900, and now at the age of 68, when many people today might be settling into their retirement, Antonio formally established his engineering business as A.Agrati & Figli at Monticello.

Upon Antonio's death in 1924, at the grand age of 92, his original workshop passed to the hands of his three sons, Clodoveo, Luigi, and Mario, who began to expand and modernise activities to the repair of agricultural steam engines. Spurred by the success of this new avenue, the Agrati Company commenced manufacture of a range of electric motors in 1925, then gears and various bicycle components, which could be produced from the same equipment to utilise full capacity of the machinery and tooling.

Tragically, all three brothers died prematurely within a short space of time, leaving the company to be inherited by Mario's widow and Clodoveo's 16-year-old son, who conceded electric motor construction in favour of the continued manufacture of cycle parts, up to the early 1940s.

Production of cycling equipment resumed after the war, until 1955, when Agrati expanded into presswork, particularly with the manufacture of frame components for motor cycles, scooters and mopeds - and now it may be possible to see two roads converging...

The first Garelli 515 model was displayed at the Milan Show in December 1955, for market sale the following year. Its fully suspended pressed-steel frame with unit-construction motor, manual clutch, three-speed gearbox, and chain final drive represented the company's first true moped.

It was about this time that Garelli made its first contact with Agrati, as a supplier of pressings and cycle parts for its new mopeds.

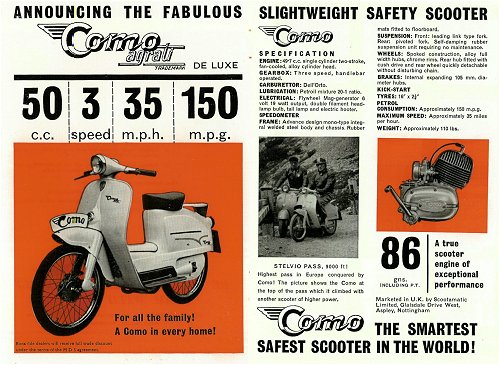

Agrati shortly took the decision to develop their own range of scooters and mopeds in competition with the established Piaggio Vespa and Innocenti Lambretta. Debuted in 1958, the Agrati Capri scooter was introduced with a 70cc two-stroke engine made by Garelli, and followed by a 50cc Como scooter model in 1960.

The Como reached the UK in November 1960

The next development was pretty obvious...

1961 found the two companies merging, to form Agrati-Garelli Gruppo Industriale, a calculated move to benefit both parties in the economic climate of the time.

Starting from a veritable bike boom at the beginning of the 1950s, as the decade wore on, worldwide motor cycle sales had been steadily reducing as greater social affluence led to increasing sales of motorcars at the cost of the two-wheeler market. Agrati & Garelli very much complemented and strengthened each other, as both brand ranges were rationalised to continue the more popular models. As well as utility mopeds, Garelli now further produced engines for agricultural equipment, chainsaws, marine outboards, go-karts and a light urban van.

The merger also presented enough capital release for Garelli to return to its competition origins with the presentation of a new three-speed 50cc sports 'Junior' motor cycle. Later fitted with a four-speed gearbox, two specially prepared and faired machines set a number of records at Monza over 3 - 4 November 1963: 6 hours average speed 75.7mph, 1,000 Kilometres at 72mph, 24 hours at 67mph and, to capitalise on the success, a production model Record Sports became popularly sold.

After 1965, the Agrati name was largely dropped from corporate branding, all motor cycles and scooters continuing thereon under the Garelli badge only.

In 1969, it was decided to completely focus Agrati-Garelli Group production back towards motor cycling, resulting in the development of the Rekord and Tiger Cross Sports mopeds, and the initiation of development of a new horizontal-cylinder engine for utility mopeds.

As something of a change, in this feature we're not specifically featuring a bike, but following the course of this new horizontal engine. In 1972, new step-through moped models with the flat-cylinder motor were introduced. The automatic 49cc engine of 40mm bore × 39mm stroke featured an iron barrel with 8:1 compression alloy head, Dell'orto SHA14/12 carburetion, and rated as 1.5bhp @ 4,500rpm.

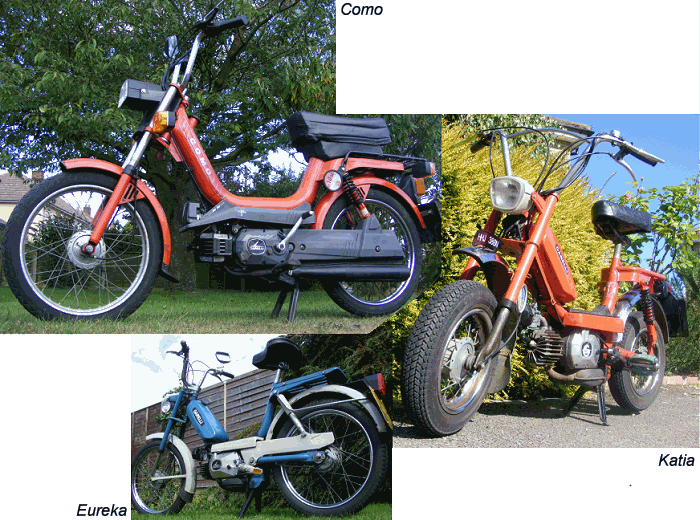

This leads to our first feature machine, a 1975 Garelli Katia 'M', with radial finned cylinder and matching head.

Katia initially came in model options:

M = single-speed automatic pedal-start moped, which introduced UK imports in January 1973.

MK = single-speed automatic with kick starting, only commenced importation in July 1977 (following UK moped reclassification)

K = two-speed automatic with kick starting, importation started April 1981.

Possibly described as 'miniature moped meets monkey bike', Katia was an appealing novelty, a tiny bike with fat little wheels covered by stainless mudguards. Small physical size and light weight made it both practical and readily transportable.

Originally, the 3" × 10" wheels were spoked onto hubs, but later versions moved to cast alloy wheels. Katia's rear carrier is of particularly sturdy construction since it comprises part of the rear frame, with the back suspension mounting from it, and a cylindrical toolbox underneath, to carry a basic two-stroke toolkit (plug spanner and spare plug).

Starting, click on the choke at the carb, pull the clutch lock lever under the left handlebar cluster, push down on a pedal, and our motor fires up on second attempt. Open the throttle wide to snap off the choke shutter.

With few hills to negotiate around its home in the Anglian flatlands, and to improve cruising speed, this machine has had a rear sprocket change from 24 teeth, down to 22 teeth. Certainly attributable to this 8% raised gearing, the single-speed motor has to labour quite hard in pulling away, and works the auto-clutch up to about 20mph when the drive locks fully home. Attempts to help the motor on take-off with a bit of pedal assistance prove completely futile, as even furious windmilling of the pedals can only achieve the equivalent of a light jogging pace, about 5mph.

With all its years of experience, you'd think Garelli might have figured out how to make the Katia go round a corner, but not so, even the smallest bumps on a bend induce a wobbly uncertainty that instantly convinces any rider not to push his luck too far on this bike. The ride feels rather bouncy at the back with the undersprung saddle and aftermarket Paioli hydraulic damped rear shocks (original shocks would have been undamped, so presumably the Paioli's are an improvement?)

The 60mph Veglia speedo doesn't work, so we resort to a pace bike, which reports happy cruising around 30mph, and up to 35mph readily achievable on the flat under favourable conditions. Pushed hard on a long downhill section, our best result was clocked by the pacer at 40mph, and seems a pretty respectable showing for such a tiddler, but an 8% gear-up to the drive ratio goes some way to account for these above-expected results.

Since rear braking operates by the left handlebar lever, back pedalling gives free rotation within the motor. Both brakes proved very effective (as they should with the tiny wheels, particularly considering these same hubs can be found in wheels of twice the circumference), but the front creaked embarrassingly as the bike came to a halt.

Despite quoting a 6 Volt, 26 Watt generator, the CEV lights prove pretty poor, and the horn croaks like a frog with a sore throat.

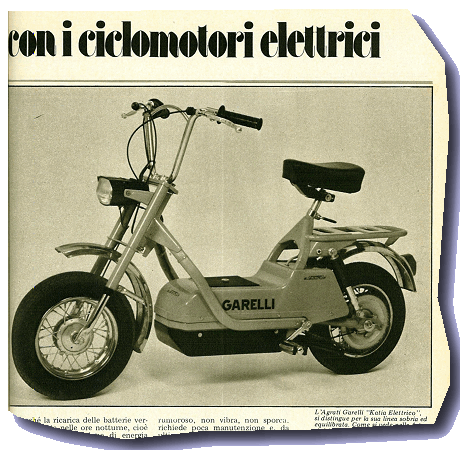

This single-speed horizontal Garelli impressed as a tough and hard working little engine, particularly so in this case, to overcome the high drive ratio. In various forms over its production years, the Katia proved a particularly successful model range, with some sources quoting worldwide sales exceeding half a million machines. Added to the line-up in 1974, one particular variant however, failed to justify its technical development. Utilising the same 24 Volt Bosch equipment and similar construction as the contemporary Solo Electra, the Electic Katia was also a sales disaster for Garelli.

Later added to the Katia range in the 1980s, were further models K11S, and Katia Matic K70 (65cc).

Onward, onward, to the end of the decade, and now we have a UK market 1979 Eureka. Another moped model mounting our Garelli flat-motor, but with different iron cylinder and alloy head castings. Power output is still given at 1.5bhp, so the change to horizontal finning patterns would appear mainly cosmetic.

Like Katia, this Eureka was another new moped type introduced with the horizontal cylinder engine, and imported to the UK from June 1972. Wheels and tyres are bigger on this model, sized at 2¼" × 16" to appeal to a more conventional sector of the market.

The Dell'orto SHA 14/12 carb with DGM10082S filter didn't manage to suppress the induction roar effectively, probably due to the intake baffling having been cut away. Induction draw wasn't actually overly loud, and some may not be bothered by the hooverish buzzing that sounded like a frantic bee in a bottle, but we felt it did get a little wearing after riding a while.

Typically of iron cylinder motors, the engine likes to get thoroughly hot before performing properly.

The best on flat result was a consistent reading, as the bike readily got up to and maintained a paced 34 actual speed, though the speedo read much slower, only indicating 29mph!

The pace bike clocked the downhill run descent at 39mph, while our speedo still remained 5mph behind the actual speed, reading only 34. Holding its descent speed pretty well on the following climb, Eureka stormed up the other side without losing much pace, and cresting the rise at 25mph. This 60mph Veglia speedo generally maintained a readout about 5mph slow of actual paced speed, so possibly goes some way to dispel the myth about generally optimistic Italian clocks!

Handling was very good, confident, well planted, and sure footed, an interesting and far better comparison to the twitchy Garelli Katia we tested earlier, showing what a difference the selection of wheel size and tyres can make.

We felt our Eureka was mostly let down in the braking department. It seemed to take a lot of lever movement to get them to start making any retarding effect, then felt like they required progressively too much more pulling force to achieve disproportionately less braking effect. For an urgent stop, the impression was that you could well find the levers pulled onto the grips as the Gates of St Peter loomed ominously closer. Particularly, the front brake also creaked disconcertingly as the bike slowed toward stationary.

Again our horizontal Garelli engine proved a good, tough, hardworking little motor, delivering a relentless performance throughout the run.

Eureka mopeds were sold in further Eureka Flex II and Eureka-Matic (two-speed) versions, up to discontinuance in April 1981.

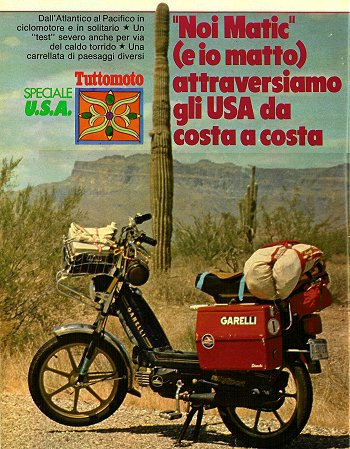

The Noi Matic's journey acros the USA

reported in Tuttomoto, September 1981

From 1981, the Eureka mopeds were superseded by a new, restyled range of Noi models, P, MK, Matic & Mag, which still employed the same flat motor. After a decade in production, the horizontal-cylinder Garelli engine was now set for the next decade.

Promoting introduction of the new Noi moped range, a coast-to-coast journey across America was undertaken during August 1980 by Italian journalist Roberto Patrignani. This same former racer had been part of the record-breaking Garelli team of 1963, and rode from Charlton, Carolina, on the Atlantic Coast, to Los Angeles, California on the Pacific Coast, to cover 2,860 miles in 16 stages, averaging 177 miles per day, to prove just what had now become possible with a modern moped. The entire run used just 19.4 gallons of petrol, giving an average consumption of 147mpg.

Under the team leadership of Daniel Agrati, Garelli returned to racing in 1982, devastating all competition as Angel Nieto and Eugeno Lazzarini swept to first and second places in the 125cc World Championship, and soundly secured the Constructors Cup. Lazzarini also finished second in the 50cc class and, during the year, the company opened a third Italian manufacturing facility and an assembly unit at Curitiba in Brazil.

New N70-Matic and N70DL-Mag 65cc models were added to the Noi range.

In 1983, worldwide Garelli production reached 130,000 units, and the 50cc racer was reported to be topping 120mph. However, while Garelli appeared to surfing a tide of their own at this time, the rest of the world two-wheeler business was sinking into motor cycling recession.

By 1985, the last wave had washed up the beach, leaving a parched reality as commercial income trickled away into a river of sand. Against a drying economic climate, the management fought back with new developments in its competition programme, campaigning a 250cc V-twin racer and 320cc trials bike. At the Milan show in November, Agrati introduced four new production machines: F1 Formuno moped, Tiger 50XLE and 125XLE trail bikes, and revised model of its popular 125GTA sports roadster, now fitted with twin-disc front braking.

Most surprisingly, the '85 show further presented new 35cc regenerations of the Mosquito cyclemotor! In a strange throwback to the past, these were again offered in cycle attachment kit form as the Bicimosquito or Velomosquito complete machine version. The cyclemotor attachments were reintroduced to complement sales within the 'Torpedo' bicycle division, and subsequently, by the motor fixing to the whole range of cycles, over 60 different models became offered - though the customer was probably bewildered by choice! From the basic roller drive cyclemotor, this introduction now represented a most extensive product selection across the Garelli small capacity range. Considering top moped models featured such developments as multi-speed gearboxes, water cooling, and pumped oil injection, it certainly seemed as if the Garelli range had all options covered.

Rather than indicating company health, the cyclemotor reintroduction actually represented a darker state of commercial desperation as the business struggled to make ends meet. Closure of its British agency during the same year, Agrati Sales Ltd at St Marks Street in Nottingham, only served to underline the depressed state of the market at this time, and the level to which sales had dried up.

For 1986, searching for salvation in competition, Agrati stumbled onward into the desert ... while the 125 racer kept on winning, the 250-V remained well off the pace.

1987, and our flat-cylinder Garelli engine marches on, this occasion finding our motor in a typical Noi type Europed of the period, and still the Como name is around, harking back to echoes from the origin of Agrati.

This Como model is helpfully accompanied by a copy of the original owner's manual, which greatly assists by providing some useful technical data. Capacity 49cc, bore 40mm × stroke 39mm, compression ratio 9:1, power 2.5bhp @ 5,000rpm. Noting the compression ratio increased by 1 point is an obvious means to extract more power from a motor, but it's also worth noting that the higher 2.5bhp rating is now quoted at 5,000rpm, where the original engine was rated 1.5bhp @ 4,500rpm. A higher bhp reading will always result from any motor at higher rpm, so it's not to be considered a wholly direct comparison.

Carburettor Dell'orto SHA 14/12 (so no change there), but the flywheel magneto is now rated at 12 Volts × 45 Watts electrical output!

The data advises two Como models being available: model K with single-speed automatic clutch, and 2K with two-speed automatic clutch.

The main frame consists of a U-formed 80mm diameter tube, running from the steering headset to underneath the seat, which releases from a catch at the back, and hinges up from the front to reveal a tool tray below. Filling with petrol from the front of the frame requires the lifting of the seat and pressing a bleed button at the bottom of the tool tray to vent trapped air from the back of the frame so the tank can fill. Forgetting this results in a startling surprise as fuel very quickly gushes all over the bike - no, please don't ask how we were reminded, thank you!

With changing European regulations regarding the qualifying classification of a moped, the motor has now traded its pedal set for a kick-start arrangement on the left hand case, and mounts a footrest assembly from underneath the engine.

The engine also looks different in that it has a black cylinder head but silver barrel: closer examination reveals the head to be blacked but, instead of an iron cylinder as on the earlier models, the barrel is now cast of aluminium and finished with a chrome bore.

The Como wheels/tyres are 2¼" × 16", the same size as the Eureka it replaced.

You have to look around for the fuel tap, which is tucked away under the left hand footplate, then a couple of jabs at the kick-start rouse the motor into life.

As soon as you sit on the saddle it becomes uncomfortably obvious that the seat foam is too soft, basically squashing down to the pan as soon as you sit on it.

This 60mph Veglia speedo consistently indicated a little fast, reading 20mph at an actual 18, best on flat was showing 36 to 37 against an actual of 33 to 34, and best downhill was suggesting 40 while the pace bike was reading this off at 37mph. The motor maintained its pace well, holding 26mph on the climb back up the other side.

There was some high frequency vibration detectable at speed, mainly through the footrests. Though this wasn't really considered any problem over our short six-mile test course, it might become significant enough to induce progressive numbness on a longer run.

Both brakes worked well, though let out a few occasional complaining squeaks in operation. A rear stop lamp operates on both levers.

Suspension was felt to be a bit soft and mushy, so the handling wasn't too confident, and the front end seemed somewhat light and nervous when riding with just one hand. The spongy ride however, failed to compensate much for the soft saddle foam, which flattened right down to the base pan and gave a hard seat that you very quickly looked forward to getting off.

Despite being an AC batteryless system, the indicators and other electrics all worked perfectly, and the 12 Volt lights were very good, producing a perceptible beam even in daylight!

While testing our Garelli Como, 1987 had proved a most dramatic year for the organisation.

Though the 125 racer took the world championship for the fifth year in succession, the 250-V only proved a complete failure.

Top level management had seen departure of the Agrati family, who would have no further involvement with the business, and closure of the old plant at Sesto San Giovanni, for consolidation at Monticello Brianza.

By the time of the Milan International Motorcycle Show in November, the heat was starting to tell. Including the Mosquito cyclemotor models, the range was right down to just six mopeds and three motor cycles: the GTA125 Gresini, Tiger 125XLE, and Trial 323.

Things were now getting really tough in the important Italian domestic market, with fierce competition from Aprilia, Cagiva, and Gilera (Piaggio), while the speed of the new Spanish Derbi and Honda singles finally eclipsed the Garelli 125 racer in the 1988 competition season.

The last new models were the 'Gary-One' and 'Gary-Duo' mopeds, before bankruptcy in 1992, which effectively concluded the Agrati chapter, thereafter presenting significant problems to owners seeking spares for earlier machines, since these are barely supported before the termination date.

47 years later, and Garelli would still appear to hold the 50cc 24-hour record at 67mph. There doesn't seem to be any evidence that anyone has ever bettered it!

Next - Sometimes the end is not the end, as our Garelli sequence goes on to become a trilogy!

Though Agrati-Garelli Gruppo Industriale certainly perished in 1992, some of its dying seeds carried on the desert winds ... far away to distant lands.

Our final chapter in this saga involves another crossover, now down to the oddball support slot, so if it's moving on to the third feature notch, then it's probably going to involve something a little off the mainstream ...

In these days of branding revival maybe it's time to ask whether you believe in Reincarnation?

[Text and photos © 2011 M Daniels. Period documents from IceniCAM Information Service.]

Our second Garelli chapter had actually been floating around for quite a while, as several disjointed road tests on various Garelli mopeds.

These were certainly in existence well before the preceding Stingers feature on the Mosquito cyclemotors was even a twinkle in our eye!

The first test in the can was Steve Cobb's Katia at Diss on the Suffolk/Norfolk border in May 2009, which was completed on location at short notice. As these things often seem to happen, Steve was saying he wanted to post the bike for sale on IceniCAM Market, so we whizzed over to take listing pictures for the ad, and completed road test notes and a photoshoot at the same time.

At this point the Katia was only a singular Garelli, so wasn't anticipated to be anything other than a single machine feature, but it wasn't much longer before Ken Howard was talking to us at an EACC rally about forthcoming changes in his stable, and the Garelli Eureka shortly going on the transfer list.

Another case of test it quick before it's gone, so it was off to Huntingdon to collect the bike for road test, photoshoot, and Market listing, from which the moped sold so quickly we barely had time to get it back to him!

The third bike was a fairly similar story, except that David Evans had already posted the Como for sale on IceniCAM Market, so we needed to be very quick with this one. Fortunately, being locally based, just on the other side of Ipswich, we caught the last of our trio.

How then to present the package was now the question?

Rather than the usual 'bike based theme', for a change, it was decided to focus on evolution and installations of the horizontal motor type over the years instead.

The article concept was there OK, but everything sat peacefully in the can, waiting for some suitable time...

The 'when' became pretty obvious as a follow-up to the Mosquito feature from issue 16 on 2 January 2011, and a research pack flew out with Danny on the 10th for the article text to be first-drafted over the following weeks in Australia.

Due to the scattered nature in which the feature was assembled, the finance department seemed to have lost grasp on precise production costs, but generally figured these to be around £35 for diesel fuel, and sponsorship is credited to Paul Efreme, East Anglian Cyclemotor Club, Essex Chapter.