Our story picks up from a 60cc Sachs Saxonette rear-mounted motor wheel in the 1930s, and you may experience a feeling of comfortable similarity to something more familiar. This Sachs unit came to be fitted into a number of cycle makes, and it was upon this engine that DKW based designs for their own motor wheel, but World War 2 intervened and the DKW derivative never went into production.

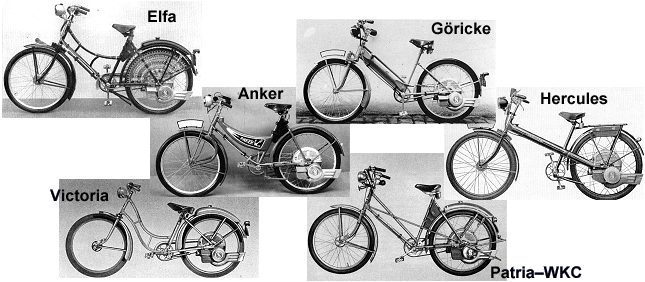

Variations on the Sachs Saxonette motor wheel

In 1948, the blueprints for the DKW cyclemotor engine were carried by DKW designer Bernhard Neumann, along with a group of German engineers sent to work at Den Haag in Holland for HNG (Hart, Nibbrig & Greeve NV—importers of cars and motor cycles), helping with development of a 2-stroke car that had been designed by DKW at Chemnitze. Neumann teamed up with Dutch designers Rinus Bruynzeel and Nico Groenerdijke to explore the DKW motor wheel drawings and produce a prototype, but, due to difficulty in working on the engine from its rear mounted arrangement, the design became adapted to a simpler and more accessible roller driven derivative mounted above the front wheel. The engineers made up the name for their new motor unit from the first two letters of each of their Christian names, Bernard, Rinus, and Nico. HNG established a new factory called Pluvier Motorenfabriek to assemble this 25.7cc cyclemotor, and in November 1949, began production of the Berini M13 though, initially, many of its components were made in England.

The original DKW cyclemotor blueprints were placed with Interpro Buro: an Anglo–American–French organisation, formed to help re-establish industry in the Netherlands after the war—which is why "Interpro Pats. Pend." may be indicated on some engine components (eg: magneto flywheel cover). Interpro then sent the DKW blueprints on to England, titled in German as ‘RadMeister’, which maybe not un-coincidentally translates as Cyclemaster.

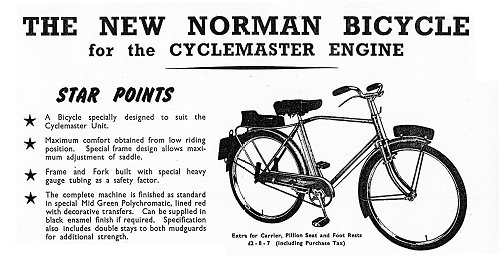

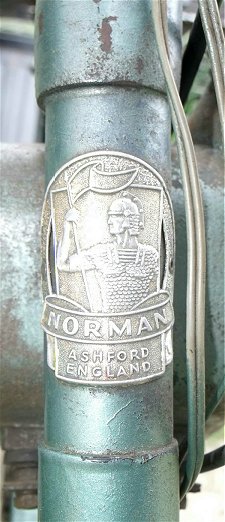

Before the Cyclemate, Norman made this cycle for the

Cyclemaster

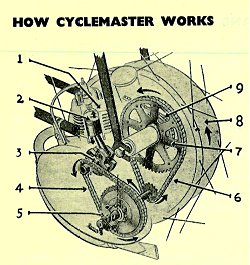

A company called Cyclemaster Ltd was established at 26 Old Brompton Road, South Kensington, London, to market the new cyclemotor units, which were manufactured by EMI Factories in Hayes, Middlesex.

By June 1950, the 25.7cc British version of the DKW RadMeister design had been launched, and found itself competing for popular cyclemotor unit sales with another nine attachment motors on the market at the time. In 1951, Cyclemaster Ltd relocated their address to 38a St George’s Drive, Victoria, London while, back in Holland, HNG increased their Berini engines to 32cc capacity in 1951. The British Cyclemaster followed suit, and increased engine capacity to 32cc in 1952. By 1954, the British cyclemotor boom however, was proving to be on the decline—sales were already being lost due to the growing popularity of new mopeds, and a greater disposable income for the customers to be able to afford more than a humble cyclemotor.

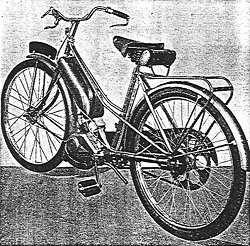

Early picture of a Cyclemate

(Note: no lights or rear

numberplate fitted yet)

Cyclemaster decided upon an ‘If you can’t beat them, join them’ approach, and adopted a plan to recycle their cyclemotor into a moped! Norman at Ashford in Kent was contracted to design and manufacture a frame, and the new Norman Cyclemate Moped was launched on the Cyclemaster stand 126 at the 1954 Earls Court Motor Cycle Show. Norman was a fairly logical choice for this project, since the company had previously engaged with EMI in licensed contract for building out later production of its Rudge autocycles from 18th December 1939, when the Hayes factories were rapidly turned over to urgent wartime production of military radio and radar equipment.

Once again, Norman’s business relationship with the parent company was brief, as Cyclemaster Ltd separated from EMI during 1955, relocating both its manufacturing operation and offices to Tudor Works in Chertsey Road, Byfleet, Weybridge, Surrey. Early in 1956 the Cyclemaster sales office moved back to London, at 154 Shepherds Bush Road.

Brochure picture of a Cyclemate ... with all its fittings

Looking round our feature Cyclemate with frame serial C4638, a few aspects are certainly going to catch the eye!

Look at that low BEC carburettor with a forward facing air filter! You have to wonder if it might be some ancient ram-air system to improve performance ... and how the engine runs in the rain? The right-hand crankcase cover was a special revision for the Cyclemate, since the Cyclemaster’s rear-facing carburettor disposition proved incompatible with the Norman frame arrangement, so the forward facing set-up was developed to enable the installation.

The sheer size of rear sprocket is quite striking too, that’s 10 inches in diameter! 64 teeth! Is that about the biggest rear sprocket we’ve ever seen on a moped!

Since the drive chain is conventional 1/2 × 3/16, the front sprocket is clearly a special that is different to the small pitch chain on a Cyclemaster engine. With the engine set so far forward and the huge rear sprocket, the drive chain run is probably about the longest you’re ever likely to see on such a small machine, 29 inches from sprocket end to end. Long chains may dictate correspondingly long chain-guards, and the Cyclemate is well endowed in this aspect too. The two-piece chain-guard shields both drive and pedal chains, since these both run on the same right hand side. The total chain-guard length is a whopping 32 inches!

There’s a 19-inch long rear carrier with number plate mounting strip across back of the carrier frame, though our example ignores this fixed strip to mount its number plate from a lamp bracket off the rear guard, and is fitted with a Lucas 590 rear lamp unit. This arrangement appears to be original, though we believe that number plate/lamp units could vary according to what fittings might be available at the time.

The original paint finish has a metallic appearance, a fashionable and popular new style of presenting many machines in the 1950s, and described in literature as ‘Completely rust-proofed by spra-granodising process, finished in attractive mid-green lustre’.

Cyclemate is quite a visual feast of unusual engineering—a fascinating combination of interesting, strange and old fashioned.

Switch the fuel tap off–on–reserve at bottom right of the tank. Starting Cyclemate is quite conventional in that you need to choke-up the carburetter, except that the BEC carburetter is practically at ground level in front of the engine. The choking device comprises a little pull-ring on the end of a short coil spring, pull to fill a secondary fuel chamber, but actual flood–overflow doesn’t occur with this type of mechanism, so you’re left holding the spring and wondering if it might have flooded enough yet ... no, can’t see anything happening ... is it full yet? Maybe just pull it a bit more to make sure ... must be done by now surely ...who can tell?

When we finally decide that we think the choke valve must have worked by now, pedal up the road and drop the clutch, the Cyclemaster engine fires up almost instantly. Even from cold the engine strums steady and regular at low revs. The small capacity engine and single-speed drive ratio means you should be expecting to pedal assist the take-off, then only feed in the clutch once you’ve got moving. You certainly won’t be doing any unassisted hill starts on one of these!

Easing up to speed down the lane, the motor starts to become quite growly and grumbly with lots of four-stroking bluster by 18mph, and within a short distance up the road, we quickly appreciate that the clutch is slipping. This proves more deeply rooted than simply over-tight cable adjustment, so we’ll have to nurse this machine up to speed. Beyond the village and turning onto the main road, our Cyclemate particularly struggles with clutch slip into the headwind, so we have to pedal assist up to running speed and take things gently on the throttle.

Starting from cold, our engine has seemed rather prone to four-stroke running under off-load throttle and on the flat, but this gradually abates as we work a bit of heat into the cylinder after a couple of miles. As the motor warms up, presumably the motor oil thins and the clutch seems less prone to slip, for which we’re grateful, so at least we can now get a proper flat impression on the downwind run.

Best on flat 22mph, which needed a thoroughly hot motor to achieve. Clocked by the pace bike, this was taken with a reasonable following wind, and neither seemed to make any significant difference in either upright or crouched positions. The limiting factor to this performance was 4-stroking break-up, so that’s pretty much the motor’s natural rev ceiling as regulated by gas transfer out of the exhaust port, while the bike steadily bumbles along to a constant flat drone from the silencer.

Both capacities of Cyclemaster motors may be quite prone to carbon build-up in their exhaust ports when run on old type mineral oils, and four-stroking can be a typical symptom of constricted spent gas venting. Considering this Cyclemate engine recalls no check on exhaust porting condition, it’s possible that a service maintained example might be capable of demonstrating a slightly better performance.

Downhill run achieved 26mph, but more a gravity related result, again being held back by constant four-stroking.

Uphill performance was really irrelevant since the engine suffered a slipping clutch and our bike required pedal assistance.

The brakes didn’t feel anything exceptional, but were adequate, and unchallenged by Cyclemate’s performance.

The forks and frame are both rigid so the 26-inch pneumatic tyres and saddle springs are providing the only effective suspension functions, though this wasn’t really any issue due to the undemanding pace of the motor.

There’s an interesting Miller model CA6 cycle headlamp fitted, with V-shaped lens, but we think this is possibly of pre-war origin and not original equipment.

Our Cyclemate has no stand, and there appears no stand lug on the frame, though our period literature indicates machines were supplied ‘Fully equipped for the road with prop stand, lamps, tools, tool bag, inflator, horn, number plates and licence holder’. It was no real matter about the absence of our stand, with the bike weighing in at just 76 pounds (34kg), and a 4-inch ground clearance to the pedals, the cycle was so light that it could easily be set on a back-pedal to ‘side stand’ against the kerb just like a bicycle.

Cyclemaster period literature vaguely quoted Cyclemate speed as 20–25mph, so we had a skim back through several old road tests to see how our result compared some 55 years down the line. Cycling in April 1958 gave exactly the same 22mph that we achieved, but testing another Cyclemate again in February 1959 only registered 20mph. In July 1955 Power and Pedal reported ‘just under 25 on flat, and up to 30 on favourable grades’.

It appeared that performance results might be quite variable according to individual machines, so, over half a century later, we were happy our results still fell into the mean of the given range.

The dwindling cyclemotor market continued to dwindle away, and by 1957 the Cyclemaster had only another five makes of cyclemotors to compete with on the British market. While the Cyclemate certainly remained among the most price-competitive machines available of the day, at just 32cc, it was technically the smallest example in the moped category, and certainly among the lowest powered and slowest of 32 different makes of moped on sale at the time—and pure cost alone was not necessarily the main factor on which many customers were basing their choice.

Cyclemaster Ltd was now desperately spreading its business to include factored sales of the Berini M22 moped and Piatti scooter in its range of listed machines.

In August 1957, the Shepherds Bush offices closed, and functions consolidated back to the Tudor Works address in a belated attempt to reduce costs.

Tough times got tougher for Cyclemaster as a creditors meeting was called in December 1957, and a rescue package proposed, but by January 1958, the business had entered into voluntary liquidation.

A new company called Planloc Engineering was formed in March 1958, to purchase the remains of the Cyclemaster business, and resume production of the Cyclemaster, Cyclemate, and Piatti scooter from Tudor Works.

Manufacture of the Piatti scooter effectively concluded toward the end of 1958 as the remaining stock of assembly components were built out, though poor sales of this machine meant that these last completed scooters would be trickling out of the factory for some while after production actually ended.

Britax (London) Ltd took over the Planloc business in 1960, briefly continuing production at Byfleet, but renaming the site as Proctor Works.

Production of the Cyclemate moped was discontinued in June 1960 and, along with the Cyclemaster and Piatti scooter, Cyclemate dropped from trade listings in 1961.

So, in the end, had recycling the Cyclemaster into the Cyclemate moped been worthwhile?

Well if success may be judged by numbers alone, in its 10-year lifespan the Cyclemaster sold over 180,000 units, and in 6 years the Cyclemate maybe just about scraped up toward 7,000 units.

Typical comparative prices of the respective units were around £33 for a Cyclemaster motor wheel kit, and £44 for a complete Cyclemate moped.

The Norman Cyclemate certainly didn’t repeat the earlier landslide sales of its cyclemotor origin. It never quite worked out the cheap moped saviour the company needed to survive, and it’s easy to see why the commercially astute EMI decided to distance itself from the Cyclemaster business in 1955, since it knew all the gold had already been dug from that mine, and it was time to move on.

At just 32cc, Cyclemate was the littlest moped, an oddity in its time that was angling for economy sales at the cheapest end of a very competitive market, where saving every last penny wasn’t always the prime factor—but the Cyclemate did have its place. There were a number more British moped and lightweight producers that would have looked enviously on such sales of 7,000 units.

Maybe the model wasn’t a great success, but it wasn’t a failure either.

Today, the Cyclemate is a fascinating oddity and it’s really nice to see some still around.

Next—Continuing a general North American theme to articles for our next edition, maybe there’s only a minor stateside reference in The Empire Strikes Back, but yes, it is genuinely there, fair & square, so it’s been decided to run this presentation in with the next batch. Excepting some obscure links to the USA, the feature rings a number of international connections that go quite some way with extensive research, and probably present the best theories yet towards answering some of the mysteries and most perennial questions about the origins and historical background to this infamous ‘British’ moped from the 1970s.

This article appeared in the

April 2013 Iceni CAM Magazine.

[Text & photographs © 2013

M Daniels. Period documents from IceniCAM Information Service.]

We'd had an eye on our Cyclemate test machine for a couple of years, with a view to ‘get round to do it sometime’. No hurry, because owner David Whatling at Horham was quite relaxed about ‘whenever we wanted it’, so the bike became an ‘incidental collection’ after the Horham Run in 2012. The road test and photoshoot were completed in June 2012, all fairly straightforward, except waiting for an opportunity for the rain to take a break—typical English summer!

Cyclemate is one of those peculiar ‘in between’ machines, not really cyclemotor, but not quite a proper moped either!

Though the frame is obviously evolved from cycle origins, it’s not really a bicycle since the design is dedicated, and the chassis specifically built to suit the motor, which itself is also a special derivative of the original cyclemotor.

A number of other odd cyclemotor-cum-moped derivatives may come to mind, the Brummi 40 with a Rex cyclemotor engine in what became the Phillips Panda frame, and the Rex–Phillips motorised cycle, the H V Powell Joybike and Talbot mopeds which both fitted Trojan engines. There are certainly a few examples of other cyclemotor engines being fitted and sold in dedicated frames, but the Norman Cyclemate is a particularly distinctive example of the craft.

Riding Cyclemate proved about as much excitement as taking the bus! This impression results in the natural expectation of comparing it to any other moped, but that correspondingly falls short because its capacity is nearly 40% less, so it's just always going to seem ‘a poor mans moped’. Cyclemate has little in the way of what one might call ‘performance’, and is hardly something that would have originally been ridden much for fun. It’s very much a commuter utility workhorse toward the very basic end of the moped spectrum. Pleasant enough today if you’re bumbling to a local country hostelry on a pleasant sunny weekend for a lunchtime glass of ale, but probably not so great if you were going to work in a factory in the 1950s for a 7:15am start on a dark, cold and rainy morning, with passing buses belching clouds of diesel toward the gutter, and the rain slashing down - which is probably the purpose for which many Cyclemates were originally bought.

A Cyclemate may be a little more enjoyable today in old-timer rally and social use, but isn’t going to have any chance of keeping up with the general pack of mopeds, autocycles and light motor cycles on club runs, so is likely to be back in the ‘slow group’ with any cyclemotor cousins, VéloSoleX and Moby Cadys.

Where Cyclemate really scores today is in unique interest, it’s fascinating and unusual, quaint and old English—and people will always come to look at it. They may not wholly know what it is, but it has some aged quality that will draw people to see.

Our photoshoot was set as we felt the Cyclemate may be found in its own natural habitat—aptly leaning against the wall of an old shed!

Production costs involved just one return journey to Horham and back, so only about £10, and another interesting little tale of motoring history for a bargain price.

Sponsorship credit went to Nick Place down in Hampshire, who we think was restoring a Honda P50 or something like that. Before his donation came out of the hat to attach to this article, we wonder if Nick previously had much inkling about the Norman Cyclemate ... probably not!