Sponsored by

Mark Crowder of Mopedbug Ltd BSA/NVT Spares,

and Gordon Mayer—EACC.

1974: World fuel crisis causes oil prices to quadruple. UK inflation hits 20% and there are two general elections within the same year, firstly with Labour in a minority government, then Labour in overall majority. Vehicle licensing becomes centrally managed from a new Driver and Vehicle Licensing Centre at Swansea and new style registration documents replace the old style buff log books.

1975: The Vietnam War ends (who won that?), and front number plates are abolished from motor cycles on 31st July. Moped road tax at this time was costing just £2.50p per year, which is conveniently the precise point we find the very earliest references to our subject... In July 1975 there was a showing where various Norton Villiers Triumph prototype motor cycle and moped models designed by Bob Trigg were presented at a London press conference by Managing Director Dennis Poore and Shadow Industry Secretary Michael Heseltine MP.

Significantly, 30 July 1975 is also the printed date appearing on a most considerable report prepared for the Secretary of State for Industries (Eric Varley), on Strategy Alternatives for the British Motorcycle Industry, much of which requires painstakingly staggering through to find a small section between pages 143–144 relating to Moped Assembly.

‘It could be possible for the British industry to purchase most components from outside suppliers overseas who have adequate volume in the manufacture of parts (or are prepared to sell at marginal cost) so that they can be obtained at a competitive price. These parts could then be assembled in the UK without incurring a major cost disadvantage.’

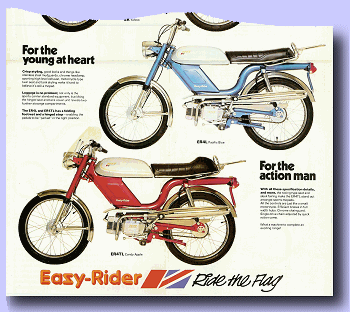

NVT Easy Rider Sports models

Spring 1976: NVT launched the new Easy Rider moped range, though it’s always been quite a point of conjecture who actually made these machines. Most of the parts were clearly factored components from Italy: Morini Franco engines, Italian hubs laced into Radaelli rims, and being supplied with fitted Pirelli tyres rather suggested the wheels came complete. The telescopic front forks were typical Italian market, as were the rear suspension units, the Domino controls, CEV headlamp, IKJ switchgear, and Brevetti high-level sports style exhaust/silencer on some models (that looks as if it was specifically made for the machine).

NVT-branded Lucia speedo

The speedo is marked ‘NVT Motorcycles’, but don’t be fooled, they didn’t actually manufacture this, it’s probably the same make as the drive: Lucia.

Having pretty much eliminated everything else, we’re left to wonder about the chassis...

The first Easy Rider ER1 and ER2 step-through automatic models were introduced in March 1976, and were assembled near Birmingham, at Shenstone in Staffordshire.

There’s some speculation that NVT made the chassis, but seems unlikely since the swing-arm and pressed steel chain guard appear on other, variously branded, Italian-built machines which are generally credited to Bianchi/Italtelai manufacture. The NVT frame however, never appears on any other Bianchi/Italtelai made bikes, though tube sizes and some forms are fairly similar, so it seems possible that Bianchi/Italtelai could have made the chassis to Bob Trigg’s specific design, so maybe the Easy Rider range wasn’t quite a totally bought-in machine assembled from off-the-peg components.

Text passages appearing in period motor cycling press publications were sometimes vague, and may have been open to misinterpretation when reporting on high profile people of the time behind NVT, like Doug Hele (who had been involved with BSA/Triumph racing teams) being credited with frame design and steering geometry, chief designer Bob Trigg being responsible for styling, and former Velocette man Bertie Goodman responsible for sourcing most of the foreign components—many of these references seem unlikely to relate to the Easy Rider moped, but more probably to the contemporary NVT Rambler motor cycle models.

The only particularly obvious Easy Rider item that you’d credit as UK manufactured could be the Lucas 679 rear light unit, being the same one typically fitted to Triumph/BSA motor cycles of the period. Presuming that the lamp unit was being fitted by NVT, then the group were also likely to be making the suitable lamp unit/number plate mounting bracket, since similar items were certainly being produced for period BSA/Triumph motor cycle models. If these lamp brackets were UK fitted, they were notably colour matched to bike frame and front fork assemblies, suggesting the brackets were being painted along with the chassis, so the frame components were seemingly being built from supplied bare metal parts.

This theory would be reinforced by the attached frame serial plate on our feature machine ‘Made by NVT Motorcycles, England. Frame no. ER4T*1009*’ and the engine being marked with matching engine serial ER 4/1009, strongly suggesting they were being stickered and stamped at the time of assembly or it’d be very difficult to tie-up the numbers.

The dedicated rear carriers on the step-through Easy Rider models are notably not completed in any matching paint, so could easily have been supplied as fully finished from anywhere.

The single and dual seats on respective Easy Rider models were proprietary purchased, leaving only unknown supply for the remaining parts on the sports styled models of the frame trim, fibreglass tank, and seat & tank mounting frame.

ER2L sports, ER4L, and ER4TL sports models were added to the listed range in November 1976.

An ER2P model was listed in April 1977, an ER2SS Silver Special model announced in May 1976, followed by an ER1SS in June 1976, both models to run till the end of the year in commemorating the Queen’s Silver Jubilee.

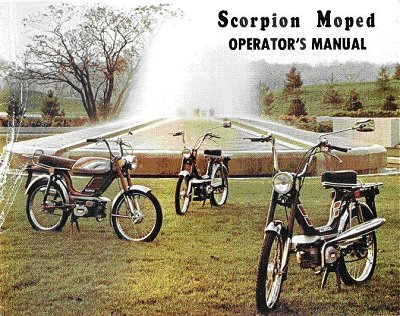

Towards the end of 1977 NVT announced the securing of export orders to the USA of 1,000 Easy Rider mopeds per month. Export market American mopeds were mainly sold as either NVT Easy Rider or, from August 1977, as Scorpion SC1 (step-through frame, single-speed auto), SC2 (step-through frame, two-speed auto), and SC-2X Scrambler models (sports styled, two-speed auto). Frame plates indicated these machines as ‘Manufactured by Scorpion Inc. Crosby, Minnesota’, a snowmobile manufacturer established from 1959, who marketed the mopeds as a product diversification.

The Scorpion models also used the same Italian manufactured Morini Franco engines, though labelled with ‘Cuyuna Motors’ stickers (an engine brand owned by Scorpion Inc), M-01 for the SC-1 model, M-02 for SC-2 and SC-2X models.

Other lesser branded versions of NVT Easy Rider mopeds may be found in the USA badged as Mizer and Lance.

It’s now come to that time for the usual look around to case out our test machine.

We haven’t got this machine in for any pretty looks, but more particularly because it’s in totally original condition with a genuine low mileage and sound running motor, so should be very fair for a totally representative test.

In this case our victim is a slightly scruffy specimen, S-suffix, so places its date of registration around 1978, though its relatively low frame no. ER4T *1009* would actually seem to be a fairly early serial in the production series.

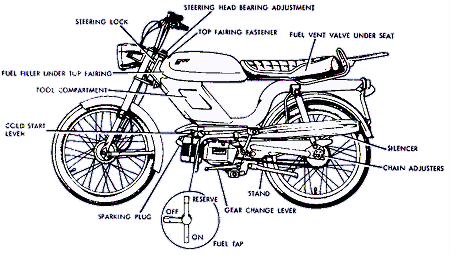

Cursed with the dreaded but now mandatory ‘Sloped’ 30mph restricted plate riveted to the headstock, the NVT 4 is an interesting carry-over example of this particular manufacturer’s way of getting round the old moped law that finally resulted in the infamous legal change of specification on 1st August 1977. The footrest/pedal set-up virtually borders on the bizarre, and any rider who was never involved in the sports moped scene of the time would probably be completely mystified as to quite what’s going on with this arrangement.

The engine mounts a conventional 180° pedal set, but there’s also a fold-down footpeg on the left-hand side so the rider has a stable rest to operate the foot-change gears. However there’s no similar footrest on the right-hand side, so you’re presumably meant to use the pedal-in-down position on this side as a rest to work the brake pedal? Now, just behind the engine casing is what looks like a fold-down footrest, but without any footrest ... so it’s just a small fold-down peg? Ahh! That stops rotation of the pedal, so the right pedal becomes a fixed footrest. Back on the other side, the left-hand pedal sticks upward, but sits behind your leg, and actually, when you sit on the bike and try it out, it does work OK ... but looks really naff!

Talking of which, one of the main features of a sports moped is that it has to have a motor cycle style tank atop the frame—above all else, it’s simply got to have that feature—that’s the rules!

Yes, a frame top tank and a dual seat, that looks to be exactly what the NVT 4 has, so it’s officially a sports moped ... but where’s the petrol cap?

The smooth tank top lines are unsullied by the interruption of any fuel filler, and hold on a minute? Why’s the petrol tap lever coming out from under the footplate and down by the engine? What’s going on here? Just put your hand under the tank ... and it isn’t! The tank is just a fibreglass edge with no bottom—it’s a dummy!

There’s a Dzus screw at the front of the tank to clip it down, but just give it a pull and the whole tank, dual seat, and rear carrier hinge from the back of the seat to reveal the real petrol tank is in the frame with the filler neck located at the top end by the headstock, and within the sporty styling box-trim that’s probably also meant to serve as toolbox—though if you actually put anything inside it’d probably drop right down to the bottom and you’d struggle to ever be able to reach it again.

As the tank and seat unit hinge up, the rear carrier hinges down, so there’s a fairly limited movement before the rack fouls the rear lamp assembly. This all rather restricts access for fuel filling, and isn’t particularly helped much by a rod/latch under the saddle that rests the tank & seat assembly in the ‘up’ position.

Just when you think it can’t get much worse ... it does! Here’s the bad news, you can’t fill the tank without pressing a bleed button to release the air at the back of the frame, and this is right underneath the back of the dual seat! You have to kneel down to reach right under the seat to work the bleed at the back, at the same time as you’re trying to fill up the tank at the front. Just imagine trying that with a pump in a petrol station. And, if you fail to bleed at the same time as filling, then the fuel floods right out of the filler neck, flushes through the toolbox, out the bottom, and drowns the engine in petrol!

So you’ve got a really naff fibreglass dummy tank with no bottom, and the most ridiculous filling faff of any bike on the planet! Anyway, we’re finally ‘gassed-up’, as they say in the colonies, and got the major gripes over ... oh, maybe not! Quite what’s a sport-moped doing with a footplate on the frame?

You can kind of understand the footplate thing on the conventional step-through Easy Rider automatic models where some continental riders like to put their feet up from the pedals (none of that nonsense going on in this country we’re pleased to say). How can the footplate have any real purpose when you’ve got a 4-speed foot-change on the left and a brake pedal on the right so you have to keep your feet on the footrest/pedal? Anyway, with the tank & dual-seat arrangement, it’s almost physically impossible to put your feet on the footplate—so it just becomes a whimsical cosmetic trim to cover the top of the engine!

Having finally finished our rant at late 1970s’ sports moped fashion styling, we guess it’s time to try the wretched thing out ... you just know we’re not going to like this, don’t you?

Positional indication of the petrol tap seems a little vague, so we study the tiny markings to try and work it out. ‘C’ (forward) on one side and ‘R’ (back), which might be ‘Close’ and ‘Reserve’ maybe, so down for on ... and there’s a growing puddle of fuel on the floor because the carburettor’s flooding!

Following a strip-down to blow out the needle valve, that problem is resolved, and moving right along ... click on the choke, it’s a Dell’orto SHA12-14 carb, so the shutter will snap release once the throttle is opened full.

You have to fold up the left footrest and the right hand peg to be able to spin the motor in neutral by use of the pedals, but one down stroke on the right pedal doesn’t turn the motor much and it fails to start, so you change over to standing on your right foot to down stroke the pedal, but it fails to start, so you, etc ... left, right, left, right ... this is hopeless, it’s bump start time: just shove it down the road, notch into first, and the motor fires up straight away.

We can’t be doing with all the faffing of this ridiculous starting ritual when the darn thing doesn’t want to go so, suffice to say, we never bothered to try pedal starting the 4L again.

The Morini Franco motor pulls off quite smartly when you let out the clutch, then quickly up to second as the gear runs out. The gearbox changes easily and selects its evenly spaced ratios well on the up-change, though often seems to find a false neutral going down from top to third, otherwise good shift and good clutch.

A rolling conference with our pace rider establishes our speedo is reading 3mph slow when we’re indicating 20, but shows nearer the mark when we get to 30.

The motor seems to pull well enough accelerating through the gears, though feels rather lacking toward higher revs in top (possibly not unexpected for a supposedly 30mph limited machine). Having now got underway, and developing a feel for the bike, 4L actually rode quite well since its proportioned more like a proper motor cycle than a flimsy moped, reasonably solid and well planted on the road, handled satisfactorily, cornered confidently on its 2.25×17 tyres, the suspension worked comfortably ... it really does ride appreciably better than expected, and somewhat shows the motor performance to be less than the chassis.

Pace bike clocked our best on flat as 36mph (still air, full crouch), on the return leg when the engine was thoroughly hot. The motor cleanly ran two-stroking at all times, the exhaust tone smooth and even, with no four-stroke breakdown at any points, which all goes to indicate an adequately dimensioned exhaust port, but limited transfer range to compromise the power.

Diving into the downhill run, dip into a crouch, building up to maximum speed, through the light bend in the lower section, engine revving hard, tucked right down now, speedo needle indicating somewhere around the 45 marker headed toward the bottom of the dip, just about to max out—OMG there’s a pheasant in the road! Where’s it going? Left, right, left, no, it doesn’t know—abort, abort!

The pheasant dives into the hedge, and though the downhill max run was spoilt, we continue with the following uphill climb just to see if the bike might make it to the crest in top gear. Our speed continues to drop away until it almost feels as if we might not make the peak, but 4L just about hobbles over the crest at 15mph.

Back again for the re-run, and while the 60mph CEV was indicating somewhere past NVT">45 toward the bottom of the downhill, our pace bike clocked this off at 41mph max. Without the panicking pheasant to contend with this time, we get a good run at the hill, and notch back to third as the pace fades (finding the false neutral again in the process) to see if the down change improves the result. Yes it does, as we crest the rise at 21mph this time, so proves use of the gears does compensate for the lack of power from the motor when hill climbing.

The footbrake was particularly snappy and could readily lock the rear wheel without really trying. The front brake proved rather less fierce and delivered a reluctant retarding service despite a high lever pressure, then complained and groaned just as the bike slowed to a stop.

The lights appeared pretty bright even in misty daylight running, which seemed fairly good for a battery-less AC 6-Volt system.

Solid and well planted on the road, 4L almost rides like a proper motor cycle, but somewhat lacks go.

Did sports moped sixteeners ever really think the NVT was cool? We think it’s naff and just too much faff!

ER2L, ER4L, and ER4TL sports styled models were all de-listed in May 1978 as the bankrupt Norton–Villiers–Triumph Group fell into liquidation.

Meanwhile, Dennis Poore had founded another company, Norton Motors (1978) Ltd, at Shenstone near Birmingham, primarily so this could continue development of the rotary-engine motor cycle inherited from BSA/Triumph. In order to make this unit self-financing, it would also continue on-going assembly of the NVT Easy Rider mopeds and Rambler motor cycles at the same site. The works also undertook some small production runs of special motor cycles for Yamaha.

The ER2P was discontinued in February 1979, and NVT branded ER1 & ER2 models dropped in April 1979, only to be immediately replaced with identical BSA badged ER1 & ER2 models, along with introduction of new Beaver and Brigand restricted 50cc sports styled four-speed motor cycle/mopeds, and an unrestricted Boxer 50 motor cycle in October 1979.

It is further reported in 1980, that production of former NVT motor cycles and mopeds continued under BSA branding from the old BSA factory at Garrett’s Green, so the Norton Shenstone site subsequently seemed to have disinherited this work as a consequence of the liquidation restructuring.

The Snowmobile Company selling Scorpion branded Easy Rider moped models in America matched a similar decline to NVT and wound up this operation in February 1980.

Occasional production of BSA branded lightweights continued at low levels to slowly use up part stocks, until the remaining ER1MK (kick-start) moped and GT50 motor cycle models were finally de-listed in December 1987.

Bob Trigg’s factored-assembly Easy Rider moped design had actually managed to remain in production for over a decade—which really was quite remarkable!

Research into who made the NVT chassis assembly looks to be leading back to Bianchi/Italtelai.

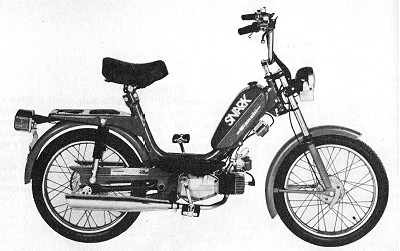

Snark was another brand name

applied to Bianchi mopeds in the US.

In 1967 Bianchi sold its motor cycle brand rights to Innocenti, but continued with Bianchi cycle manufacture, which they still do today, being one of the main Italian bicycle manufacturers ... but it appears that they also retained rights to Bianchi-branded moped manufacture, including other export brands of Pacer, Lazer, and Negrini, particularly into the US market.

It seems the NVT moped frame building subcontract was initially established with Bianchi Cycles in 1975, who carried the model into production, and forward to market sale in 1976.

In 1978 Bianchi’s moped business was sold on to Italtelai Corporation

Italtelai would presumably have inherited the NVT frame manufacturing contract with transfer of business. After Italtelai took over, Snark branded moped models were also introduced in the US.

NVT ER2L, ER4L, and ER4TL sports styled models were all de-listed in May 1978, which was a particularly significant year as the NVT organisation re-structured to BSA branding and the Snowmobile Company selling Scorpion branded Easy Rider moped models in America matched a similar decline to NVT, to finally wind up its own operation in February 1980.

Is it significant that Scorpion Inc’s business concerned considerable glass fibre moulding for snowmobile manufacture, so might have had some involvement in production of tank-top mouldings for the sports-styled moped models? All the timings could fit, but is particularly difficult to identify and confirm quite who was manufacturing what on the sports styled models.

Italtelai branded moped models were sold in the USA 1978–83, imported by Marina Mobili, and also marketed by PMBI as a ‘Portofino’ branded moped (Portofino Motori Bologna Italia?).

BSA branded Easy Rider ER1MK models continued on listings until December 1987, but sales under BSA branding were generally quite low and may have been maintained on ‘reserve stock’ after Italtelai business seems to have ceased in 1984.

We have been unable to trace anything further of what actually happened to the Italtelai organisation. The company name still seems to be registered in Bologna, though the Italtelai title appears dormant, and the registration still retains copyright to Bianchi’s old Lazer branding.

Next—This article has been rattling about in the can for a while, nearly making it to publication at this very time last year, only to be eclipsed at the twelfth hour by the Folders feature. Completing the oriental theme for next edition, what could be more suitable than the most successful 50 of all time? This little motoring giant grew to be mightier than the Morris Minor, more massive than the Mini, and crushed the Beetle by its absolutely staggering production numbers—and it all began with the ‘Iron Horse’.

But considering the size of the two other features, will there be room to squeeze this in—or will Iron Horse become edited out in the final cut again

This article appeared in the

July 2013 Iceni CAM Magazine.

[Text & photographs © 2013

M Daniels. Period documents from IceniCAM Information Service.]

Who actually made the NVT Easy Rider moped has been quite some point of conjecture in moped circles for a long time. Over the years there’s been lots of speculation, but when it came down to some of our deepest research, we don’t seem to recall that anyone actually guessed the most likely source.

The Easy Rider models were designed by Bob Trigg in 1975, and chassis seemingly initially manufactured by Bianchi, then later by Italtelai, who bought out Bianchi moped rights in 1978.

Our North American theme connection came with Scorpion branded models sold by the Crosby snowmobile manufacturer.

Remarkably, the Easy Rider moped officially remained listed up to December 1987, an incredible run of over 10 years production! Might that make it the most successfully produced ‘British’ moped? Though most of the parts came from Italy...

Equally remarkably, was that the Easy Rider survived through some of the most troubled times in the British motor cycling industry. If the business bankruptcies and strikes didn’t get it, then surely the politics of the day should, but Easy Rider endured to finally fade away from old age and public indifference to the fate of the last British-branded moped.

How NVT came about—Triumph motor cycles had been owned by BSA since 1951 but, by 1972, the whole business group was in deep financial trouble. British Government policy at the time attempted to save strategic industries with taxpayers’ money, and since BSA–Triumph had won the Queen’s Awards for Exports just a few years earlier, the industry was deemed to qualify for financial support.

The conservative Government under Ted Heath concluded that, to bail out the company under terms that to compete with Japanese imports, it should be merged with the equally troubled Norton Villiers (which represented the remains of Associated Motor Cycles, salvaged by the British engineering conglomerate of Manganese Bronze).

The merged company was created in 1973, with Manganese Bronze trading off the motor cycle parts of Norton Villiers in exchange for the non-motorcycling bits of the BSA Group—primarily Carbodies Company, and builder of the classic Austin FX4 London black taxicab.

While the Triumph brand was felt to retain a better export recognition, so the BSA name was deliberately dropped away as it was perceived to represent a ‘lower profile, home-market brand’. The failed remains of practically all that represented the once great British motor cycle industry now became consolidated into one element called Norton–Villiers–Triumph, and inherited four motor cycle plants—the former BSA factory at Small Heath in Birmngham, Triumph at Meridan, and Norton–Villiers units at Andover and Wolverhampton.

Though the Meridan factory was the most modern, it had also acquired quite some reputation for union militancy, and worst productivity of all the sites.

In July 1975, new Industry Minister, Eric Varley, recalled a £4 million government loan, and declined to renew the company’s export credit guarantees, so plunging the entire NVT business into receivership. Redundancy notices were served to staff across all sites. The Wolverhampton site closed within 3 months with over 1,500 job losses, but Meridan survived through another government loan by establishment of a workers co-operative to continue manufacture of the Triumph Bonneville.

It’s remarkable to consider that the Easy Rider was created in the very midst of this turbulent financial and political maelstrom, the product of a business already in the process of administration!

NVT was finally liquidated in 1978, but in one form, then another, the moped survived; built in one place, assembled somewhere else; under one badge, then a different logo; with pedals, without pedals. The Easy Rider just kept coming back, time and time again...

Our featured four-speed sports model came from sports moped fan Antony Austin at Northampton. Some careful planning reduced some potential expense of fuel costs in doubling up the trip by picking up 3 of his bikes on the way back from the FBHVC AGM in October 2012, but there were still two round trips, there and back, and some 400+ miles of diesel fuel in the equation.

Since all-up costs were split with bikes from two other features, it’s probably fair to place costs for The Empire Strikes Back around £50. We’d had a standing specific NVT sponsorship credit on the books from Gordon Mayer for some time, which was further joined by Mark Crowder for Mopedbug Ltd, a fairly recently established small business providing parts for NVT and BSA Easy Rider mopeds, + Brigand and Beaver small motor cycle models.

I was intrigued by the story about NVT Easy Rider mopeds and Puch mopeds as I was selling both marques during my time as a motorcycle dealer in the post-1973 period.

The NVT Easy Rider range of mopeds were made entirely at the Shenstone near Litchfield factory at the same time Norton were developing the rotary engines at the same premises. The frame and cycle parts were designed and had been originally conceived by Bertie Goodman who had been with Velocette at Hall Green, Birmingham until they went into liquidation. However, these were the days when Norton–Villiers–Triumph were collecting together the remaining talent left over from the demise of BSA Automotive Group in October 1973.

Having been made redundant from Triumph Engineering Co Ltd, late of Meriden, I was by the spring of 1974 trading as a motorcycle dealer myself, selling Honda, Puch, Jawa–CZ, Derbi, and NVT products.

Having been in the motorcycle industry since 1954, I was very aware of just was going on following the demise of motor cycle production in the UK, as most of my friends were involved. Bob Trigg had been involved with Ariel; Doug Hele with Douglas, Norton, Triumph; Jack Harper was with NVT having prior to 1973 been employed by BSA, man and boy. One must remember that, by the 1970s, not only had the British motor cycle industry failed but also the infrastructure that went with had suffered the same fate.

So, if we want to make mopeds, or indeed any powered two-wheeler, where does one go. The obvious place is where the product is being made in quantity and much of this was at that time being made in Italy, Germany, France, and the Netherlands, with Italy being the major player. The NVT range of mopeds was mostly made of components, including the Moto-Morini engines, entirely sourced in Italy. Italian factories were turning out mopeds in vast quantities.

Steyr–Daimler–Puch A G in Austria had been around since 1864 and had become Austria’s second largest employer after World War 2 employing some 18,000 people making cars, tractors, motor cycles,mopeds, bearings (steyr) on a massive scale and selling their products world wide. However, their production of powered two-wheelers (and bicycles) had never been on the same scale as the, by then, increasing competition from the far east.

SDP were, by the 1980s, up against intense competition from the Japanese manufacturers and, basically, with their backs to the wall, hence the demise of their two-wheeled products and they had some advanced powered two-wheelers in the experimental stages some of which was passed on to Hero Industries in India who made an effort but the end product as regards build quality was rubbish.

The whole issue with NVT was victim of power politics and the BSA name came back in to the equation briefly in Coventry where they made or rather assembled the Rambler & Brigand Yamaha-engined models at a factory in Tile Hill, Coventry.

I still see frequently one of my friends, Harold Hackett who worked for BSA originally as a tester. We often have a laugh about the days when I worked at Meriden and, together with one of my fellow testers, would give Harold and his mate John a good ‘buzzing’ on our ‘B’ range Triumph 650cc twins when we came across Harold and John road testing BSA Bantams or BSA C15s, etc. With the passage of time most of us old timers who actually worked in the British motor cycle industry are becoming increasingly thin on the ground, and the true stories are being lost. As the saying goes, every picture tells a story, but as always happens, much of the truth is lost with journalistic licence.

My days in the motor cycle trade were definitely the happiest of my working life and 60 years on I still enjoy riding anything on two wheels.

Triumph Hinckley are still making a success of manufacturing motor cycles having moved into the twenty first century as a world player, with factory sources in Thailand, Brazil, and India.

An excellent and accurate book on The Strange Death of the British Motorcycle Industry was published in 2012 written by Steve Koerner who has produced a very comprehensive and thoroughly researched 350-page epistle on the subject—a first class read (ISBN: 190547203X).

Happy days indeed and I hope the foregoing might add a little to the next CAM magazine.

It sometimes works out that when we present an article on a particular bike then, subsequent to publication, additional information may come to light. This has indeed become another such case—regarding our July 2013 presentation on the NVT Easy Rider, which went into quite some exhaustive research efforts to establish the source of its cycle parts.

While processing some further related material for the library archives, an article on NVT found in the June 1978 edition of Which Bike briefly noted within its text, a singular curious reference to ‘Verlicchi frame’ … and led to a little more research to investigate what this might be about … and it appears to refer to an Italian company called Verlicchi Nino e Figli SpA.

In 1934 Nino Verlicchi (1914–96) with his brother Giuseppe opened a small workshop at via S Carlo, in the centre of Bologna, for the production of tubular steel structures, particularly handlebars and exhaust pipes for the local motor cycle industry. The Bologna motor cycle business was then led by now long-gone brands CM (Mario Cavedagna), GD (Ghirardi & Dall’Oglio), and MM (Mario Mazzetti). Following World War 2, Nino Verlicchi re-opened the workshop in 1946 and, thanks to experience gained in military engineering service during the war, began to design complete bicycle and motor cycle frames. It was during this period that Verlicchi patented and produced the first innovative concepts of integral suspension supported frame designs for the Ducati Cucciolo engine.

The increasing popularity of small engines within these frame types quickly led to growth of the business and, in 1950, the company relocated to a 300m² industrial building in via Andrea Costa, Bologna, and expanded to a workforce of 20 employees.

During the 1950s, Verlicchi cemented a close working relationship with the Italian motor cycle industry and soon became the main supplier of cycle components to Cimatti, Ducati, Malanca, Mondial, Morini and BM–Bonvicini (Moto BM).

By 1964 Verlicchi had acquired a new 3,000m² factory in Croce di Casalecchio, and now extended its staff to 100.

The new premises were immediately organised for maximum efficiency, with specialised departments for each step of the frame production process, which allowed Verlicchi to further broaden its business in the early 1970s by securing sales to other Italian manufacturers like Fantic, Laverda, Minarelli and Moto Guzzi, as well as wider European customers of Norton and Triumph in Britain, and Zündapp in Germany.

This period saw years of the greatest popularity of a new chassis design by Nino Verlicchi, this frame established a reputation for ready adaptability to installation of various engine types and service reliability, and came to equip a large range of models for major manufacturers such as Benelli, Fantic, Moto Morini and Villa, for more than a decade.

In 1972 Verlicchi inaugurated its 16,000m² factory in Zola Predosa, close to Bologna, which is still the company’s operating centre today. In addition to further expansion of production departments, the company created an independent technical department to work with customers in design, development, and bringing new products to manufacture, which subsequently led to establishing supply relationships with major international partners such as Honda Motor Co.

In the early 1980s the advent of aluminium processing for lightweight frames introduced the first mass made production alloy chassis for Bimota in 1984, and led to similar products over the following years for Aprilia, Beta, Cagiva, Ducati, Montesa and Yamaha.

In 1990 Verlicchi became a supplier for BMW motor cycles, and by 1993 to BMW cars. In the early 1990s the company entered design and manufacture of special light alloy frames for high-end market mountain bikes and road cycles, and in 1997 the Verlicchi team won the downhill world cup.

1997 also inaugurated Verlicchi Casoli Srl on a 21,000m² site close to Chieti for mass production of steel frames and components, initially to cater for growing requirements from the nearby Honda Italia plant, but further production lines for other customers were soon added.

The business continued with further involvement in BMW lightweight alloy vehicle chassis development.

Verlicchi is basically a specialised trade frame maker, who has built chassis and supplied proprietary parts for many major moped, motor cycle and automotive manufacturers over the years, but has never produced any complete vehicle under its own branding.

Maybe now it becomes more obvious why so many Italian moped frames appear so similar, and often feature common components. Verlicchi produced frame assemblies and components for many moped and motor cycle manufacturers over the decades—including it appears, for the NVT/BSA Easy Rider models.