During 1943 in wartime Italy, Torinese designer Aldo Farinelli began work to develop a very small capacity engine that could be used as a ‘clip-on’ attachment to virtually any bicycle. This 39mm bore × 40mm four-stroke engine displaced 47.8cc but called ‘48’ for convenience. When the prototype was test-running around Turin in 1944, Farinelli noted the engine produced a barking tone from its exhaust, and called his motor Cucciolo (little pup).

Although Italy signed an armistice with the Allies on 8 September 1943, Germany still occupied the north of the country and it was not until 29 April 1945 when the remaining German forces in Italy surrendered, that the Italian industrial and commercial sector could try to recover by rebuilding its factories and launching new products. One such company was SIATA (Società Italiana Auto Trasformazioni Accessori) which, in 1945, was already able to restart its workshops in Turin and announce at the Turin Motor Show on 26 July 1945 that it would producing Farinelli’s Cucciolo engine along with the mountings to attach it to virtually any bicycle.

SIATA Cucciolo T1

The first T1—a model with a 9mm Feroldi carburettor—was produced mainly in 1945 and only sold locally in the Turin area. The design was modified and, by March 1946, the first ten pre-production Cucciolo di Tipo T1-b were completed, and subsequently presented at the Milan Trade Fair in September 1946.

SIATA–Ducati Cucciolo T1

Following the Trade Fair, it was obvious that incoming orders for the Cucciolo were far greater than SIATA, as a small specialist sports car tuning and parts manufacturer, would be able to manage! It became clear right away that SIATA didn’t have anywhere near the capacity required to satisfy the high demand for the motor. After a few months, the Ducati Company, with finance from Italy’s IRI nationalised investment bank, acquired the Cucciolo production rights from Farinelli and SIATA to expand production, though SIATA still retained marketing rights. Ducati revised the design to better suit volume production with the most notable difference being the cylinder fining changing to horizontal.

In the same year Ducati made further alterations to improve on the original T1; the the T2 design can be distinguished by the horizontal ribs on the crankcases.

Given the delicate situation of the Ducati brothers’ financing, the IRI bank soon took control of Ducati completely and, while the engine gambit didn’t work out in favour for the Ducati family, it would become a massive success for the Ducati company.

The Cucciolo T0 was a cheaper version of the T1, with no clutch or gearbox. The ‘fixed speed’ engine camshaft, which also acted as the primary gear, had only one lobe with one normal rocker arm and one ‘special arm’. The side case showed a blank where the clutch arm mounting point was fitted on the T1. It was built by SIATA but sold by Ducati, and only for 1949.

Under the guidance of Giovanni Florio, the first engine designed entirely at Ducati, the T3, went into production. As natural derivation of the first Cucciolo, the T3 had a three-speed gearbox and grease lubricated valve gear enclosed in a case. In 1949, a special tubular frame with rear suspension was developed for the T3 by Caproni of Rovereto, a famous wartime producer of aeroplanes. The complete Cucciolo T3 came out in the summer of 1949. In July of the same year Ducati started to manufacture its first real complete motor cycle: the Ducati 60, which was a 60cc development of the Cucciolo with kickstart, three-speed gearbox, and enclosed rocker gear & valves.

While tantalising items on the Ducati Cucciolo had been appearing in the British motor cycle press, like Brussels Show reports in The Motor Cycle from 19 February 1948, and culminating in a road test by Motor Cycling published in its 8 December 1949 issue, the cyclemotor wasn’t yet available in the UK. It would be the following year before Britax (London) Ltd. 115-129 Carlton Vale, London, NW6 were announced in The Motor Cycle of 20 April 1950that UK Ducati Concessionaires would begin imports so that the T2 Cucciolo cyclemotor engine kit became available in Britain.

We’ve previously tested a couple of Cucciolos that didn’t seem up to expectations, so we’re hoping this might be third time lucky…

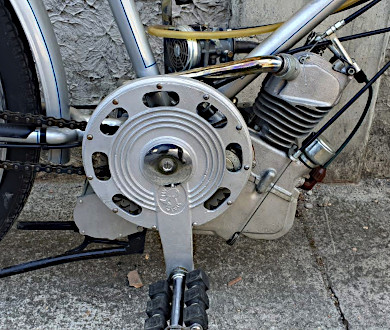

Engine 270863 is a T2 type dated to 1952, with exposed valve gear operated by pull-rods, probably built to the original 1.25bhp rating, and assembled into a gent’s Raleigh bicycle with Webb sprung forks, which would be expected to somewhat ‘soften’ road feedback from the front.

The Raleigh rolls on 26 × 1⅜ wheels, with a front hub brake; a second Radnalls calliper front brake is linked to an upper rear calliper brake and operated by the right-hand lever. A foot-operated left-hand heel-back brake works the lower rear caliper … that’s if you can find the pedal (this is the strongest brake, because of the mechanics of foot power). So technically four brakes you could potentially operate at the same time, but only if you might be able to co-ordinate all your actions to achieve this.

Two front brakes…

…and two rear brakes

The left-hand handlebar has three levers, with the clutch lever at the bottom, decompressor at the top, and the hub front brake lever in the middle.

There is also the three-position gear lever located to the front right of the steering headset with neutral between low and high.

At this point you are probably beginning to wonder if this bike was constructed for a human octopus … though there is another unusual aspect of the motor design that can be helpful to humans, once you have familiarised yourself with changing gear without using the gear lever: the gearbox has another way of selecting the gears!

Set the left-hand pedal forward to pre-select low gear, pull in the clutch to engage first, release the clutch to go.

Set the right-hand pedal forward to pre-select high gear, pull in the clutch to locate second, release the clutch to go.

Neutral is pre-selected by setting the pedals vertically (one up, one down), pull in the clutch and release for neutral.

Since all gear positions can be pre-engaged by these means, the gear lever only really needs to be used occasionally as a manual override. The only downside is the clutch lever proves quite ‘heavy’ in operation. We rarely come across pre-select gearboxes these days, probably the last being on the BSA Dandy in Jan 2011.

Starting options are: engage a gear, pull in the valve lifter lever, pedal off and drop the lever; or pedal off in neutral and just knock it into gear.

The original carb would have been a 9mm Weber, but this bike is fitted with a 10mm (⅜") Amal, with an integral cast-in body for the air filter. The shutter choke strangler on this Amal carb is operated by a rod, so either fully open or fully closed, with very little feel for fine control in between. This is OK for initial starting fully closed, but when the motor starts coughing and then is switched straight to fully open, it tends to die. You have to work a plan to get round the need to run it warm in partial open position, which involves selecting neutral and hopping off the bike so you can see the strangler and fine adjust it by hand to a suitable semi-choked position.

Fuel is turned on by a Ewarts plunger tap with the head on the left-hand side, pull on and twist to lock … and in case you may be wondering why the fuel tank might look strangely familiar, it’s made from an old fire extinguisher! There are no lights fitted to this bike, so it’s strictly limited to daylight running only.

It is paced at 33–34 on flat, 37–38 downhill, which leads us to that eternal question of how fast can a Cucciolo really go?

There’s a lot of possible answers to this question, and a lot of variables to consider…

Drive ratios: the engine comes with two standard gear ratios, and though bottom gear feels very low when pulling away, and top gear feels relatively high when you switch up, the gear ratios are fairly evenly spaced when you look at the maths: first = 13:1 and second = 7.5:1. The final drive ratio can be further varied according to what cycle sprocket is fitted on the rear wheel hub.

If the rear hub is fitted with a fixed wheel sprocket, then there will be an engine braking effect when the throttle is closed, but if the rear hub is fitted with a freewheel sprocket, then the bike will ‘coast’ when you back of the throttle.

A wheel with three-speed epicyclic cycle rear hub could also be fitted, which would offer the prospect of six gears (three in first and three more in second), or maybe even more in a racing bike with derailleur gears.

‘Half-by-eighth’ cycle rear sprockets come very cheaply in a wide range of sizes and tooth numbers, so it’s easily possible to infinitely tune the top final drive ratio for optimum speed under ideal conditions if that’s what is required.

Apart from the gearing, there’s also engine output: Power was initially given at 1.25bhp@5,200rpm, but in October 1952 the carburettor venturi was slightly enlarged, reportedly increasing output to 1.58bhp at higher revs, subsequent to which, stronger valve springs were fitted to resolve valve bounce issues, so the later motors maybe went a little better, with maximum power quoted at 5,500rpm.

Then there’s the period road tests: from economy adverts promoting eight miles for a penny and 25–30mph, to some tests of early motors on standard period cycles by stout gentlemen sitting bolt upright in flailing duffle coats reporting that ‘up to 35mph can be achieved’. While later track tests featured modified Britax frames with race saddles and rear footrests to enable a tight crouch, piloted by lithe jockeys in skin-tight leather suits claiming speeds over 59mph!

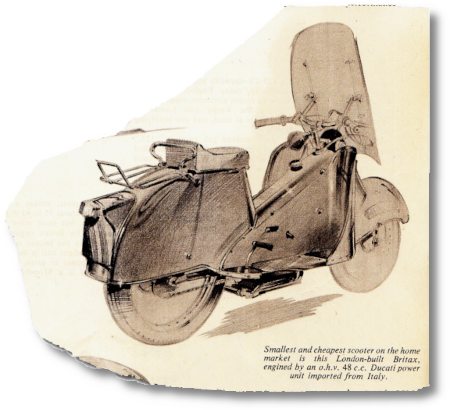

Cucciolo cyclemotors do have a reputation as being quite hard on the bicycle frames they are mounted in, since they can push a bicycle up to 30mph+ speeds that standard bicycles are not normally accustomed to cope with, particularly on poor condition road surfaces. As a result of the general introduction of cyclemotors, many cycle constructors began producing heavy-duty frames specifically for mounting cyclemotors on. British market heavy-duty frames were produced under brands BSA, Elswick, Hopper, Mercury, New Hudson, Norman, Phillips, Sun, Sunbeam, Triumph, and others, so it was no surprise that Britax would announce a frame of their own for the Cucciolo by July 1953. The cycle frame was designed and built for them by Royal Enfield, complete with the fuel tank, and pressed-steel girder forks with rubber-band suspension, which were actually just hand-me-downs from the wartime 125cc RE1 ‘Flying Flea’. This complete machine sold as frame with engine, was initially planned to be called the Britax Monarch, but this name was dropped before launch and subsequently simply known as Britax Cucciolo.

The ‘unfortunately styled Scooterette’

The new M55 Cucciolo moped was further factored through from Ducati in 1954, and joined in 1955 by two other Britax models based on the Cucciolo cyclemotor engine, as an unfortunately styled ‘Scooterette’, and racer styled ‘Hurricane’. Both sold poorly and were withdrawn in 1956 as Britax passed on its stock of Cucciolo spare parts to KVP Motors in September, but continued selling their complete units presumably until the last of the stock cleared toward the end of the year when the Cucciolo was notified as discontinued and Britax returned to the accessory business.

The Cucciolo cyclemotor was dropped from manufacture in 1958 as Ducati progressed into further light motor cycles and two-stroke mopeds.