The Beginning—Les Ateliers de la Motobécane was officially created at 10 minutes past 2 in the afternoon on 27 March 1923 when Jules Benezech recorded the company with the Tribunal de Commerce de la Seine. The company was registered with a capital of 500,000 Francs, situated at 13 rue Beaurepair, Pantin with Abel Bardin nominated as directeur général. Although he founded the company, Jules Benezech has been largely forgotten by history, content to take a back seat while his two friends, Charles Benoît and Abel Bardin are remembered as the fathers of Motobécane; they designed their first motor cycle in 1923, a 175cc single cylinder two-stroke.

Motobécane MB1

Photo: Mémoire

du Cycle

The name ‘Motobécane’ is a compound of ‘moto’ (being French for ‘motor cycle’), and ‘bécane’ (being French slang for ‘bike’). By the end of 1925 the 175 was still the only model being produced, and expanding the range into larger capacity machines would mean breaking into the market of other established and larger manufacturers. This would involve a degree of commercial risk, so a new Motoconfort company was created on 26 December 1925, and registered at 3 rue Hoche, Pantin. That way, if the launch of the new 308cc Motoconfort motor cycle ended in disaster, then ongoing production of the Motobécane MB1 would not be compromised. This spreading of risk further continued with the creation of Novi in 1926 to produce the electrical equipment for the two marques.

By 1928 the larger motor cycles had established themselves in the market and the decision was made to merge the two ranges. Both distinct Motobécane and Motoconfort brands would remain, but now the full range of machines would be offered under both marques using different model prefixes for Motobécane and Motoconfort. This had the advantage that, with dealers throughout France signed up to either brand, all these outlets would now be able to offer the full range of machines. In the same year of 1928, another ‘risk aversion’ sub-company called Polymécanique was also created to become responsible for engine production and manufacture of machine tools for the motor cycle and vélomoteur production lines. During the 1930s the Motobécane and Motoconfort catalogues differed by picturing the machines from opposite sides, but after World War 2, even this distinction would gradually disappear. As the years passed, more dealers became joint Motobécane–Motoconfort outlets, and there began to seem less purpose to retaining the two names.

Following World War 2, Motobécane began manufacture of a super lightweight ‘Poney’ vélomoteur of 63cc. It soon became apparent that a popular new ‘economy’ transport was developing around 50cc pedal-assisted motors, so Motobécane reduced the Poney’s capacity. At the behest of Willem Kaptein, Motobécane set about the construction of a prototype in 1949 based on the assembly of existing components from other machines built onto a pre-war bicycle frame, which was strengthened for the purpose. Utilising the 50cc version of the ‘Poney’ motor, the new machine was little more than a basic and simple motorised bicycle. With direct drive, its primary belt to a fixed flywheel was tensioned by adjusting the engine, then the final drive chain tightened by movement of the rear wheel. Titled as a ‘Mobylette’, the new AV3 was first presented to an enthusiastic public at the 1949 Utrecht Autumn Fair, with its French debut soon afterwards at that year’s Paris Salon.

During the peak of Mobylette moped popularity in the 1970s, Motobécane was reportedly building around three quarters of a million machines each year but, by 1980, the moped party was running out of road, the traditional moped was falling out of favour to more modern scooters, and the commercial situation was getting desperate as sales slumped.

Have we covered an Enduro style off-road bike in IceniCAM before? I can’t think of one…

An Enduro may not seem like the sort of bike that we might be covering, though our general brief covers vehicles below 100cc capacity, and this bike is just 80cc, over forty years old, and qualifies for UK historic vehicle classification.

Other justifications for presenting this machine are that it’s branded as Motobécane, was presented at a particularly crucial time when the company was experiencing a major commercial crisis, and it’s a pretty unusual machine with an interesting story.

Manufacturing dates are indicated 1981–83, but it’s not a model that was formally exported to the UK, so you probably shouldn’t expect to be seeing many of these around. The cylinder is piston-ported and specified as 48mm bore × 43mm stroke = 77.8cc, with 10:1 compression ratio, 6-speed gearbox, 18mm Amal carb and uses premix fuel (no Pozilube), with electronic ignition, and Motobécane’s rating from the Mines certificate is 7.4bhp @ 6,000rpm, and quoted for 75km/h.

It’s fitted with matching Veglia clocks, which both include the ‘M’ logo printed at the bottom of the dial, with rev counter on the left indicating up to 10,000rpm and red-line marked at 7,500, and speedo on the right marked to 120km/h.

It has an 8.2 litre steel fuel tank (with 1.8 litre reserve). Front brake 110mm & rear brake 115mm, with a switch operating on the rear brake plate to operate a back brake light. Dry weight is given as 77kg, though when we ran it across the scales the weights read as 37kg front + 47kg rear, so total weight 84kg wet.

With matching engine & frame numbers 3735 … the frame plate says ‘Made in Spain’! Hold on, not made in France? What? Looking around the bike might give other clues to its origin, so we’re going to have to give this a thorough check over.

Well, it has Akront (Spanish) rims, though the Luxor/ULO headlamp and tail lamp (French) look kosher, but there’s cheap and tacky CEV plastic switchgear (since when did Motobécane start fitting Italian switches?). The left-hand switch cluster has a blue rocker to switch lights off & on, a black rocker switch headlamp hi–lo, black horn button and red stop button. The right-hand switch operates indicators L–off–R. There is no battery on this bike, so it seems the whole electrical system is probably AC?

Why does it have indicators? Would a serious Enduro bike have indicators? Surely indicators would only be required for on-road applications, so is this just a pretentious off-road bike that’s really intended primarily for road use? It certainly looks the part, with long travel telescopic front forks and mono-shock rear, and the alloy gully rims 21-inch front wheel with 2.50 tyre & 18-inch rear wheel with 3.00 tyre, but the knobbly tyres are surely going to give a gnarly ride on tarmac?

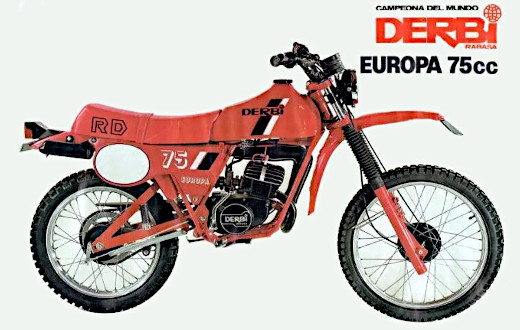

There seems a lot of Ideal proprietary parts, like the steel lever brackets and rubber lever covers, the throttle control and grips, Ideal fuel tap, and Ideal top and bottom fork yokes, but there are Derbi logos cast into the lower fork legs, and a Derbi logo cast into the inlet manifold … that really clinches it, the frame, the engine, the M80E was definitely built by Derbi, and factored to order by Motobécane. But why?

Motobécane must have been getting really desperate at this time, to be buying in a machine from another manufacturer, instead of making it themselves.

So what’s going on here?

The frame plate indicates the French Mines approval registered on 20 March 1981, so this model only became effective for home market sales after this date, and a frame number of 3735 might suggest at least three to four thousand being involved in the production batch.

The model that Motobécane decided to factor in to try and save its crumbling business was the Derbi RD75 rated 7.5bhp @ 6,800rpm, and it’s interesting that the Motobécane rating for the same machine was presented as 7.4bhp & 6,000rpm, and quoted for 75km/h … so why would that be, because it’s the same machine, just with different branding? There could be a reason…

From April 1st 1980, a new European market ‘light motor cycle’ qualification was applied according to the legal regulation of driving licence class 1b, for which a maximum 80cc, maximum 80km/h, & maximum 6,000rpm specification was set.

This change caught out a number of small motor cycles, including the new Honda CY80, which suddenly failed to meet the new max revs requirement as its motor spec was 47.5mm bore × 45mm stroke for 79cc, 9.7:1 compression ratio, and rated 5.5bhp @ 7,500rpm. The CY80 was 1,500rpm above the new class 1b spec, and therefore classified as a motor cycle when it was first registered, so the driver needed the open licence class-1 for this small capacity two-wheeler, and its appeal on the continent was very greatly reduced.

The further introduction of StVZO regulations requiring the use of daytime running lights didn’t help either, as the CY80 6V electrical generator output was never designed to keep up with continuous use lighting, so the indicators failed to function as the battery drained.

The result was that the CY80’s sales prospects were stuffed before it had much opportunity to appeal to anyone, so a stroke of the accountants red pen found the model smitten from history before it had chance to even make any history. The CY80 was just produced in quite limited numbers from 1980–82 and only sold in a few markets, so quickly became a rare model.

The Derbi RD75/Motobécane M80E had exactly the same problem, it was technically quoted 800rpm over the new spec.

What this suggests is that Motobécane placed the manufacturing order with Derbi well before April 1st April 1980, because they didn’t appreciate that the Derbi RD75 wouldn’t comply with of the coming regulation change. So it looks as if they maybe conveniently ‘interpreted the specification figures differently’ to comply with the new light motor cycle licence 1b regulations, so they could still sell the bikes.

Our featured M80E is indicating only 2,800km on the odometer, which seems very credible considering the good original condition of machine, so we’re hopeful of a representative road test. The fuel tap is marked C(closed), A(on), and R(res), then push down the rod at upper back of the carburettor to close the choke (which lifts off as the throttle is opened).

Mounting the 33-inch saddle height isn’t so easy when it’s 4 inches higher than your inside leg, so flick up the side-stand on the left-hand side, to lean the bike over toward you, then swing your leg over the saddle and stand flat on your left foot so you can fold out the kick-start with your right foot… Err, that kick-start is barely five inches long, and there looks to be a kick-starter stop bracket on the frame with a rubber buffer, presumably intended to restrict the kick-start to just half a stroke. This limited action means it barely allows two revolutions of the motor, however closer examination of the kick-starter arc reveals that it actually rides past the stop, and when the kick-start springs back up again it fails to even make contact with the return buffer on the clutch cover. All the evidence suggests this is probably not the original kick-start, but we have to make the best of it, though note that the folding foot peg doesn’t fold up, and the metal teeth on the foot peg could look somewhat foreboding for your shin if this kick-starting doesn’t work out.

Instead of risky kick-starting with your instep, the safer option of kick-starting with your heel means the ball of your foot stops safely on the top of the footrest when the kick-starter overrides the stop.

Then we’re most surprised as the motor starts right up within just a couple of jabs!

The exhaust proves more silenced than expected, though the motor produces more mechanical noise than expected and sounds rather harsh and angry.

The gear lever is on the left, one-down + five-up, yes, a 6-speed gearbox in an 80cc motor from over 40 years ago.

In first gear it seems as if you open the throttle and the rev counter needle just goes straight through the red-line! It’s like you’ve barely got moving before you’re having to change up, and second gear feels much the same so, before you know it, you’re already in third, and still another three gears to go! You quickly lose track of which gear you’re actually in, and tend to just keep switching the shifts up or down as required without really knowing where you are, until you reach top or bottom of the box.

The bike performs capably for its capacity, though its power band noticeably peaks towards the upper revs, while the constant gear changing soon becomes wearing.

Riding the M80, you soon acclimatise to the mechanical noise from the engine and just learn to ignore it as your confidence increases, that’s how it is and we just hope it doesn’t decide to let go.

Speeds in the lower gears weren’t anything we wanted to try, since the motor was revving past the red line. In sixth, we saw our fastest indicated speed of 80km/h on a long light downhill run, which was clocked by our pacer at 48mph, indicating the speedo was more accurate than we expected it to be (80km/h = 49.71mph).

The rear brake was the one mainly relied upon, since the front brake proved fairly ineffective.

The suspension soaked up road conditions easily enough, handling was fine with the wide handlebars helping to hold a line confidently, but there was a reluctance to trust the knobbly tyres when it came to cornering at speed.

It’s a thrash bike for teenagers … the next step up from a moped.

The Ending—Motobécane filed for bankruptcy in 1981, to subsequently re-structure the company as MBK.

A motor cycle production and marketing tie-up between the new MBK and Yamaha was first established in 1982, as the Japanese company acquired a proportion of shares and staked an initial claim in supporting the new MBK business.

By 1984, Yamaha had secured a controlling number of MBK shares and recreated it as another new company, now called MBK Industrie.

MBK Industrie formally became part of the Yamaha group in 1985.

By 1989 Yamaha had secured 99% of controlling shares of MBK Industrie.

The Mobylette moped continued under MBK branding, but produced in fading numbers as the years rolled on. Despite French fondness for continuing the Mobylette, in the end it was doomed by impending European anti-pollution legislation that was due to come into force in 2003.

The Moby two-stroke engine couldn’t meet the upcoming new vehicle emissions standards, so the last French built Mobylette rolled off the production line in November 2002.

MBK continues under Yamaha ownership as a European manufacturing plant at Saint-Quentin in North East France, building Yamaha branded scooters and motor cycles up to 700cc.