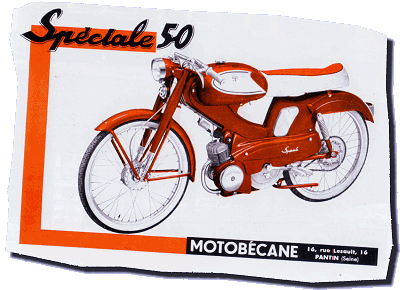

Unveiled at the Paris Salon in December 1960, the French Motobécane company surprised everybody by presenting a somewhat unexpected machine among its latest range for the coming year: its new sports-styled Spéciale 50 moped was a dramatic step from the practical and utility traditional commuter mopeds that Motobécane had produced before.

It was finished in Chaudron bronze with a small motor cycle style top-tank trimmed by cream panels, low handlebars, telescopic forks, and a skinny tyre-hugging front mudguard, but without the bulky fully-enclosed chain-guarding of its AV89 Luxamatic contemporary.

Since the youth of the day was becoming increasingly attracted to Italian-styled sports models, and Motobécane didn’t want this generation of potential new customers to be slipping away, the SP50 was made to look smart and fast to appeal especially to this younger age group. The Spéciale also went well, thanks to its variated 2.7bhp motor, with 9:1 compression and H14mm Gurtner carburettor.

The SP50 was shortly followed by another ‘toned down’ Spéciale Route sports model for more practical comfort, having a chunkier style of larger capacity top-tank fitted with chrome panels on its sides, the same heavily valanced front mudguard and fully enclosed chain-guard of the AV89, and a larger round headlamp set. It was still finished in Chaudron bronze and mounted the same sporty low–forward handlebar, but was more ‘functional’ for a mature appeal.

Within just a few years, the Spéciale Route version seemed to be more widely taken up as the more popular selling road–sports model, and became more generally known as Sports Spéciale as it adopted a more comfortable cruiser level handlebar.

The original SP50 model with its round tank was discontinued in 1963, though other later versions of the stripped-down ‘teen appeal’ SP50 did continue into the late 1960s, having adopted the same chrome panelled tank, and mounting a smaller rectangular Luxor headlamp that was also commonly fitted to commuter models.

In Britain, imports of the SP50 finished in January 1963.

The original SP50 Spéciale evolved into an SP50R Spéciale version, and was imported into the UK from June 1965. The ‘R’ had adopted the larger capacity fuel tank that was fitted with chrome panels on its sides. The front mudguard had now become the same heavily-valanced guard of the AV89, while the same fully enclosed chain-guard set was also added. The telescopic forks carried the larger round Luxor headlamp, it now had the higher ‘cruiser’ level handlebars, and was finished all in a sombre black.

To be honest, the new sports model now looked rather less nimble and sporty, but more like a clumsy and heavily armoured battleship!

Our featured bike dates from 1967, and is still finished in its original black for the UK market, but this later edition model is now fitted with a rectangular headlamp. Its AV89 motor has progressed to the later pattern square-finned cylinder, though it still has the same 9:1 compression, big ports, H14mm Gurtner carb, and rates at a full-blown standard 2.7bhp.

There’s an odd feature to this machine: it has what Motobécane call a ‘pedal locking device’, where the right-hand pedal arm can be disengaged, then turned 180°, and re-engaged so that both pedals can be set to dangle down. Maybe quite relaxing for cruising in a straight line, but the first time you come to a corner and dig in a pedal on the turn—maybe then you’re probably going to come to grief and wish you’d never touched it!

Our bike is probably not going to be up to peak performance because of its condition; some faults are obvious, like the exhaust pipe is loose and jangling from the engine because the joint is broken to the silencer, so it manages a noisy impression of a Lancaster bomber.

Despite its general state, and our suspicion that it may be a little off-tune, our SP50R still went surprisingly well (and made a lot of noise), though its Huret 60mph speedometer was obviously faster than the bike, indicating up to 50mph on the dial, which we knew straight away wasn’t going to be credible.

Consultation with our pacer reported 39mph clocked along the flat on the Sat-nav, but the bike failed to improve on this on the downhill run because of upper range misfiring from the broken exhaust disrupting high speed scavenging in the motor. That’s a typical effect of lost back-pressure at revs, and with the exhaust reconnected, there’s little doubt that it would have gone quicker.

Even with the broken exhaust the bike still went fast enough to make you throttle back on long sweeping bends. OK, the sloshy handling from the old and tired Hutchinson 2.25×18 tyres wasn’t great, and the back end wallowed from the swinging-arm suspension and undamped spring shocks, but it would go fast enough to make you think twice about whether you were really brave enough to try taking the bends at full speed.

Both brakes were good, but they are 100mm Atom hubs, so you expect that.

At this point we move to something of a flashback, and begin another parallel story, and at a time well before there even was a Motobécane company…

During the early 19th century, the Spanish Gárate family established a series of metal processing workshops in the Basque area of Spain, comprising foundries, forges, and iron works. In 1848 these were grouped under the name of Gárate, Anitua y Compañía SA, to specialise in the manufacture of small arms and rifles, which could be branded with the abbreviated logo of G.A.C.

In 1915 the company also started making bicycles but, during the Spanish Civil War (1936–39), the GAC factories were very badly damaged from aircraft bombing by General Franco and the German Luftwaffe. The cycle facilities were extensively wrecked, and it was 1942 before production of bicycles could be resumed at Eibar.

With the growth of interest in economic motorised transport after World War 2, in 1951 GAC signed a 10-year renewable contract with Motobécane to manufacture its designs under licence.

Fifty-cc models from AV3–AV33, and the 63cc AV63 (Pony) were produced with ‘local’ variations to the designs, until renewal of the licensing contract in 1961; then new models AV27, AV45, & AV60 were introduced in 1962.

1963 brought in further models: the AV32 Popular, AV65, AV68, AV88, and the GAC SP50 Sport, which is the particular subject of our interest—so let’s see how the Spanish version compares against the real thing.

The French Motobécane SP50R Spéciale was the original model that the GAC was based on, and our GAC SP50 seems to have the same sports motor cycle style top tank with chrome panels and a dual seat, and to all intents and purposes appears to be the same as a Motobécane SP50, but look a little closer…

The wheels have the same and very distinctive Rigida Chrolux C-section 18-inch rims, though that 100mm rear hub is not an Atom hub, but appears to be some sort of Spanish copy. And it’s fitted with a 54-tooth rear sprocket (the French SP50 & AV89 have 48 as standard), so the GAC looks to be running lower gearing.

The 80mm front brake again appears to be a Spanish copy of an 80mm Atom hub (whereas the French SP50 & AV89 were fitted with a 100mm front hub).

The GAC has a variator, but runs a light gauge drive belt, and smaller 210mm belt flywheel (rather than the larger 250mm flywheel and heavier gauge drive belt of the SP50 & AV89).

Investigating the carburetter, it seems an odd combination of various Gurtner carburetter parts, but is not actually recognisable as any specific Gurtner model. The Vimar 12/10 carburetter is sized from 12mm on the filter side, down to 10mm on the engine side (in a similar manner to that Dell’orto employs). It has the same filter screen and choke mechanism as a Gurtner, but the float is imprinted ‘G.A.C. Mobylette’, so we reckon it’s remade by GAC to a licensed design. The Vimar is obviously of Gurtner derivation, with a BA-series type air filter, but moulded in clear plastic instead of Phenolic.

Though the cylinder barrel is a round split-fin, it has limited exhaust porting, 20mm wide by only 7mm high (like the old continuous-fin cylinders), which is pretty certain to cause four-stroking as it gets up to revs, because of restricted scavenging ability through the small port.

The cylinder head is a matching round-fin/high-link, but just a domed hemisphere inside, so the compression ratio is probably only a lowly 6.5:1 (like the old AV78 and some AV88 models).

The GAC motor is obviously built to a restricted specification, and we don’t know its power rating (maybe around 1.5bhp?) but we’re guessing its performance is going to be quite limited.

It’s also unusual to find a ‘blunderbuss’ type exhaust mounted to this model SP50—Motobécane never fitted that exhaust type to this model.

We find the GAC frame number, 293083 which dates the bike at 1969.

There’s an intriguing telescopic rear carrier, which has a section that pulls out against internal springs, seemingly just to clamp on box packages (which seems a very narrow usage application)?

Starting procedure is typical Mobylette: turn on the fuel tap at the back centre underneath the tank, trigger the choke, twist forward to decompress, push down on a pedal to get the motor spinning, then twist back the throttle. A couple of attempts finds the motor coughing into life, then it’s a matter of tweaking the choke trigger a couple of times to get the engine to start running freely, then hold on light throttle for 30 seconds or so till it runs clear of smoke.

With the engine now seeming settled, it looks as if we’re ready to go.

With a 60km/h speedometer of dubious calibration, our course will be tracked by a pace vehicle.

Opening the throttle delivers capable enough torque for pulling away, which is obviously assisted by the variator and low drive ratio, and feels satisfactory enough for the 100 yards to the crossroads junction. Pulling away from the junction again, the bike feels fine as the variator begins its change-up around an indicated 20km/h—which is about the point where you suddenly become very aware of the lack of power being produced by the motor.

It may look like a Motobécane SP50, but this engine is a very anaemic version of the AV89! While the ratio increases as the variator changes up, the feeble motor labours against the rising gearing. We cross the indicated 30km/h mid-point on the dial steadily enough, and hold on the throttle to cross an indicated 40km/h, but this doesn’t feel like 25mph, so we’re developing some suspicion that the speedo might be a little optimistic…

We manage to wring a best on-flat in upright stance speedometer indication with the needle waving somewhere around 45km+, before pulling up at the end of the straight to compare notes with our pacer—oh dear, only 23mph. That speedometer really was optimistic, possibly intended to compensate for the miserable and obviously restricted performance. Never mind, we’ve got the motor thoroughly hot now, so maybe we might do a little better on the return run in a crouch. Tucked down as tight as we can and holding on the throttle for half a mile sees an indicated 53km/h, which our pacer confirms at just 26mph.

Over-geared and under-powered, there seems little doubt that our Spanish Sports-50 was built to comply with a 40km/h European limited specification.

The rear brake was adequate for the performance, but not as effective as we’d normally expect a 100mm brake to be on a comparable Atom hub, while the 80mm front brake was quite poor, and based on slowing a bike that barely manages 25mph, that’s very much a comment that should be read as criticism.

By comparison, the Spanish GAC SP50 really wasn’t very good at all, and little more than a mere shadow of ‘The Real Thing’.

GAC models AV44 & AV49 were added in 1965, then replaced by the AV49MR in 1969, while the SP50 became the SP-R, and was joined by an AV-188MR.

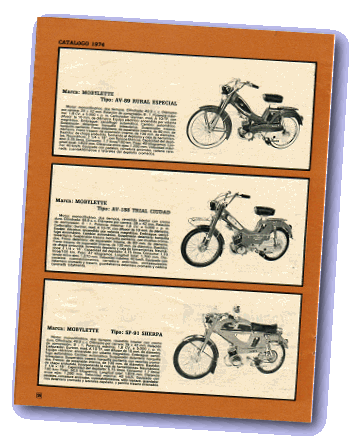

Some of the 1974 GAC–Mobylettes

With a further licence renewal in 1971 came an AV89 model, AV69, SP-94 Supercross, and SP90 to succeed the SP-R.

Many subsequent models tended to be cosmetic variations of earlier machines, the most popular of which was probably the SP95 Campera from 1972–2003, which was actually a derivative of the SP50.

1975 introduced a 50cc D-55 four-speed sports-styled motor cycle at the Barcelona Motor Show, then in 1976, an SP-96 Gran Turismo De Luxe version of the Campera, with indicators, electronic ignition, and new blue & white colour scheme.

In 1977, GAC moved from Eibar to new facilities at a 100,000m² site in Abadiano.

This new factory was established to bring practically all components of the moped to in-house manufacture, excepting just some plastic mouldings, the cast alloy wheels, switches, and carburettors.

As the Motobécane licence was coming up for renewal again in 1981 according to the terms of the ten-year agreement, problems seemed to arise with the Spanish Ministry of Industry, which resulted in GAC only achieving an extension for a further three years.

During this time the French Motobécane company suffered a major financial crisis, resulting in a reorganisation as MBK and its incorporation by Yamaha, after which the new business seemed unwilling to continue collaboration with the Spanish GAC Company. MBK then referred the re-licensing contract approval to Yamaha Central in Europe, who forwarded the documentation to Semsa Yamaha Spain.

In June of 1985, the contract conditions from Semsa, as received by the GAC directors, were considered unacceptable so, after 33 years of business, they decided to break ties with MBK and continue alone.

After the break in July 1985, GAC had to embark on period of restructuring its business, and rationalisation of its staffing levels, progressively reducing from 525 down to a target of 360 by 1990.

While continuing to retail its old French-derived machines that the company had been selling for more than 25 years, GAC embarked on a series of updates to the Gallic models, along with design and development to production and marketing of a new moped product range toward a planned debut in 1989.

The company title was changed to Motogac in February 1989, to distinguish the new motorised business from its former production of GAC bicycles.

While production in 1986 had achieved 12,530 units, increased to 16,212 in 1987, 19,000 in 1988 and 25,347 in 1989, this represented insufficient profit to support the business investment costs of some 925 million Pesetas over the restructuring period, and in 1991 Motogac registered a ‘Suspension of Payments’ (which represents an alternative to bankruptcy, enabling the trader to deal with temporary financial difficulties by authorising them to suspend their payments to creditors for a given period of time).

In 1992 Motogac re-launched as a Joint Stock Company by the issue of shares, and presented its return with a restyled Kanowey model with electric-starting at the Valencia Motor Cycle Show, and some other mopeds that were planned to be manufactured under licence from the firm Peterson of Taiwan.

The Taiwanese models, however, failed to materialise and Motogac continued with a more modest plan involving further production of traditional models: Rural AV-90, Campera SP-95R, Cady and Kanowey.

Toward the end of 1993, Motogac’s manufacturing seemed to falter and, after months of inactivity, the El Mundo newspaper reported a return to production in May 1994, then further published articles about the launch of a new GAC scooter in August 1994.

In 1996, GAC presented its new Motorino model as Spain’s simplest and cheapest basic moped.

At the Barcelona Motor Show from 7th–11th February 2001, GAC presented its latest catalogue, which still comprised mainly its traditional models: the Rural, Campera, Motorino, and a new three-wheeled version of the Cady called the Cady-Tri.

It was a last gasp, but too late, as sales in the sector were too depressed.

A general meeting of shareholders of Geacé Ciclos SA was convened for May 22nd–23rd 2001, to present a plan to dissolve the business and, by May 28th, the liquidation notice was posted.

It wasn’t until two years later that the Universal Shareholders Meeting unanimously agreed the final liquidation and dissolution of the business, which was published in the BORME No.98 on May 28th 2003.

The last French Mobylette moped actually made in France was produced in 2002, finally a victim of changing fashions and failure of its two-stroke motor to comply with the demands of increasing emission standards.

Thanks however to some joint venture projects established earlier with the former Motobécane company, versions of the traditional Mobylette moped still continued limited production in Moroccan and Tunisian factories, producing between them a further 4,600 mopeds.

The last production home of the Motobécane moped became the Turkish Beldeyama firm (20% owned by Yamaha), which continued on-going manufacture under the Mobylette name.