Edgar T Westbury was born on December 30th 1896, into a family of humble background, and received only a basic primary school education, though he supplemented this with evening classes. He signed to join the Royal Navy in 1915, until being demobilized in 1922 at the rank of Chief Petty Officer and Engine Room Artificer. After working for two years as a consulting engineer, ETW rejoined the forces with the RAF as a civilian laboratory assistant at Cranwell Training Establishment, during which time he began to publish contributions in Model Engineering magazine.

Initial engineering projects included a model aircraft that was powered by a 52cc Atom engine of his own design, then going on to build and publish reports on over 30 different original designs or derivations of his model internal combustion engines. Designs varied from single-cylinder air-cooled two-strokes to include flat-twins, OHV four-stroke singles, to water-cooled twin or in-line fours with side or overhead valves, and even an OHC in-line four-cylinder motor of 30cc called the ‘Sea Lion’.

ETW was a prolific model engineer, draughtsman, and creator of extensive designs of internal combustion and steam engines, as well as model aircraft and boats that were powered by his own motors. He became known to model engineers worldwide through his many designs and considerable contributions to Model Engineering magazine, becoming technical assistant to Managing Editor Percival Marshall in 1932, and then he was appointed as Technical Editor in 1945.

In the late 1920s ETW claimed to have experimented with one of his 52cc Atom-1 engines attached to the handlebars of a bicycle, and fitted with a 24-inch propeller for a level speed of 10mph, and to assist in climbing moderate gradients. Several early motor cycling pioneers had experimented with this highly dangerous means of propulsion, including Alessandro Anzani, and the Kendrick Aerocycle of 1930, but it was a drive system that clearly held no prospects for very obvious reasons.

Edgar Westbury must have been influenced by the publication news of Dick Ostler’s 25cc Mini Auto roller-drive cyclemotor model engine in the Model Engineer magazine’s 20th January 1949 edition. On 29th March 1951 ETW began publication of a lengthy series of articles up to 20th September, detailing drawings, including photographs and instructions to produce his own design ‘Busy Bee’ cyclemotor engine, including fabrication of the fuel tank, engine mounting plates, lift mechanism, exhaust system and silencer, decompression unit, and drive roller.

On 14th September Model Engineer magazine published a brief description and photograph of a completed Busy Bee engine displayed on the Myford Engineering stand at the Workshop Equipment and Model Engineering Exhibition. Included as a footnote in a further comment under a separate heading, ‘IC engines at the ME Exhibition’, was the report that ‘Busy Bee sets of castings will be available from Messrs Braid Bros of Hackbridge, Surrey’.

Braid Brothers commissioned all the basic castings and advertised the kit to model engineers wanting to make their own Busy Bee cyclemotor, by sending an SAE for a comprehensive catalogue. The components catalogue listed alternatives for the cylinder: BEE-5 cast iron cylinder for 10/- or a BEE-22 De Luxe cast aluminium cylinder with chrome molybdenum steel liner for £1/5/-.

As Braid Bros. sold each casting set, they also supplied an engine number slip, which gave the owner an engine number to stamp on the flange of the cylinder to comply with the Road Traffic Act for road use. Engine serial tickets above number 400 are known to have been issued, which may give some idea of the number of kits sold, though the proportion of these actually completed is likely to be somewhat less.

Our featured Busy Bee came as a long term uncompleted engine kit with no carburettor, no exhaust, no mountings, and no fuel tank. Since customers could chose to take a cheaper option and buy only ‘partial’ kits of components under the premise they might prefer to make their own parts, or buy further production castings later as they progressed their project, many Busy Bee motors could display varying degrees of originality or improvised parts.

Our Busy Bee engine is mounted on a Hercules ‘Sports’ 23-inch Gent’s model-P frame, which is identified by a decal on the down tube. The frame is fitted with a Hercules three-speed rear hub dated 1949 (though this is only a licence-built Sturmey–Archer hub with the shell stamped ‘Hercules’). Sparks come from a Wipac Bantamag. The carburettor is an Amal 308 with 5/16 inch bore, and the inlet manifold extended by a rubber pipe to stop heat transference boiling the float chamber (apparently these engines run so hot that they can do that!)

We’re told the Bee starts easily from cold. Just choke up to start, then open clear when it starts to cough, but it just peters out, so we have to re-choke a couple of times before she continues to run clear. The Busy Bee engine displays good torque right from cold, and paced to a best of 21mph on Sat Nav, its top speed held back by four-stroking preventing further revs, and vibration sets in when the motor starts four-stroking. While the torque proves useful against hills or headwinds, Busy Bees are reportedly prone to overheating and seizing from insufficient cooling, so it’s a delicate balance to get them to work.

An odd ‘deflector’ piston shape employs a deep-ported scavenge top to the transfer and exhaust port, and coupled with quite restrictive drilled holes in the cylinder wall for intake gas and exhaust venting, it’s very difficult to see the bizarre design achieving much efficiency at revs.

The peculiar shaped piston seemed to be an unproven experiment that ETW was simply trying out on this engine, because we can’t think of anything else quite like it. There was quite a fad for original interpretations of two-stroke porting and piston crown design going on through the post-war period, as various designers sought to find the best efficiency. Typically imaginative examples were Honda’s piston crown on the Model-F engine, and Piatti’s deep-ported transfer arrangement of the Mini-Motor, while other Italian makes also employed sculpted crown forms in a bid to direct gas flow. Subsequent two-stoke development however proved they were all dead ends.

The crankcase journal doesn’t have any conventional modern crank sealing, but relies on a phosphor bronze bush, so runs on a heavy 15:1 mineral petroil mix. You can’t run this type of motor on modern semi-synthetic oils.

Because ETW was fiercely insistent on use of Imperial sized specifications, the Busy Bee motor is strictly specified at 1⅝ inch bore by 1½ inch stroke, which actually works out just under 51cc.

Mr Bowers’s Busy Bee

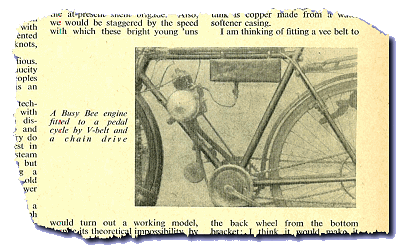

The engine was intended for use in different orientations if required, and so that it might be used in wider applications than just a cyclemotor. It could be built with either a horizontal or vertical cylinder, or mounted for front or rear propulsion on a cyclemotor. Being horizontally mounted over the rear wheel seemed to become adopted as the normal arrangement for a cyclemotor installation, possibly because that was the way that ETW arranged his first demonstration model, however a Mr F Bowers of Manchester alternatively mounted his Busy Bee within the frame diamond of a bicycle, with a V-belt drive to the bottom bracket spindle.

The horizontal and backward facing rear-mounted arrangement was surely the worst possible scenario for this motor, since the airflow was obstructed by the rider, the cylinder fins were inadequate, and orientated in the wrong plane.

Period reports barely even hinted at there being any problems with cooling, but the Busy Bee certainly developed a quietly whispered reputation as a seizure prone engine. Maybe suggesting shortcomings of such a holy design wasn’t permitted?

The Busy Bee would probably have suffered less ‘temperature issues’ if it had been forced air-cooled by a fan through a shroud, or vertically mounted over the front wheel to get a clear airflow. The De Luxe cast aluminium cylinder would probably have proved better at dispersing heat than the basic cast iron cylinder, which was obviously more popularly bought because of its appreciably lower cost.

Considering that Edgar T Westbury was 55 years old at the time he completed his first Busy Bee cyclemotor engine, we do wonder how much serious riding and testing he actually performed on the model. Since the casting kit seemed to go straight on sale as soon as his very first model was completed, he was clearly a man who had the utmost confidence in his own designs.

Along with the published Busy Bee plans and drawings, ETW even designed a temporary mounting for the completed engine, which recommended ‘it should be carefully run-in by means of an electric motor or other source of power, before any attempt is made to run it under its own power’. This might be interpreted that he could have recognised there may be seizure issues with the engine, and was recommending some ‘damage limitation’ by bench bedding-in of the motor.

Along with introduction of the Busy Bee in September 1951, was published a note ‘Coming shortly—forced air-cooled 50cc stationary engine called ‘The Bumble Bee’—but it was 1954 before the ‘stationary’ motor version was actually introduced (primarily intended for motorising a lawnmower), by which time its capacity had been increased to 3.1in³ (approx 66cc) by having a larger bore.

Because of the nature of the Busy Bee being a model engine, there isn’t really any definitive date when the motor was discontinued as such. Braid Brothers would presumably have continued selling castings to enquirers as long as they had them in stock, which may well have been quite some time after they stopped bothering to advertise the kits.

ETW died on Sunday May 3rd 1970, and his obituary appeared in Model Engineer’s 5th June 1970 edition.