If you’re not familiar with this brand of machine, then it would not be surprising to presume the name came from Italy, but Berini originated in the Netherlands.

The name came about in 1948, as the blueprints for a

pre-war design of DKW cyclemotor engine were carried by DKW

designer Bernhard Neumann, along with a group of German engineers

sent to work at Den Haag in Holland for HNG (Hart, Nibbrig &

Greeve NV—importers of cars and

motor cycles), where they were helping with development of a

two-stroke car that had been designed by DKW at Chemnitze.

The name came about in 1948, as the blueprints for a

pre-war design of DKW cyclemotor engine were carried by DKW

designer Bernhard Neumann, along with a group of German engineers

sent to work at Den Haag in Holland for HNG (Hart, Nibbrig &

Greeve NV—importers of cars and

motor cycles), where they were helping with development of a

two-stroke car that had been designed by DKW at Chemnitze.

Neumann teamed up with Dutch designers Rinus Bruynzeel and Nico Groenerdijke to explore the DKW motor-wheel drawings and produce a prototype, but due to difficulty in working on the engine from its rear-mounted arrangement, the design was adapted to a simpler and more accessible roller driven derivative installed above the front wheel.

The engineers made up the name for their new motor unit from the first two letters of each of their Christian names, Bernard, Rinus, and Nico: Berini.

The original DKW cyclemotor blueprints were placed with Interpro Buro: an Anglo–American–French organisation formed to help re-establish industry in the Netherlands after the war—which is why ‘Interpro Pats. Pend.’ may be indicated on some engine components (eg: the magneto flywheel cover.

Interpro then sent the DKW blueprints on to England, titled in German as ‘Radmeister’, which maybe not un-coincidentally translates as Cyclemaster.

HNG established a new factory called Pluvier Motorenfabriek to assemble the 25.7cc roller-driven cyclemotor, and in November 1949, began production of the Berini M13, though initially, many of its components were made in England.

HNG also presented a pre-production M14 Radmeister motor-wheel in the 26cc size from 1949, though the motor unit for this machine was believed to have been made by Cyclemaster in the UK, then built up with imported wheels and assembled into a Dutch frame, where the Berini M14 was sold in the Netherlands as a complete machine. Radmeister/Cyclemaster motor-wheels never quite caught on in the Netherlands the same as they did in Britain, and the M14 was discontinued in 1953.

Cyclemaster Ltd was established as a new company at 26 Old Brompton Road, South Kensington, London, to market the new motor-wheel cyclemotor units, which were manufactured by EMI Factories in Hayes, Middlesex.

By June 1950, the 25.7cc British version of the DKW Radmeister design had been launched, and found itself competing for popular cyclemotor unit sales with another nine attachment motors on the British market at the time.

In 1951, Cyclemaster Ltd relocated its address to 38a St George’s Drive, Victoria, London, and began importation and distribution of the Berini M13 cyclemotor kit, while back in Holland, HNG increased its Berini M13 engine capacity to 32cc during the year.

The British Cyclemaster followed suit, and increased

engine capacity to 32cc in

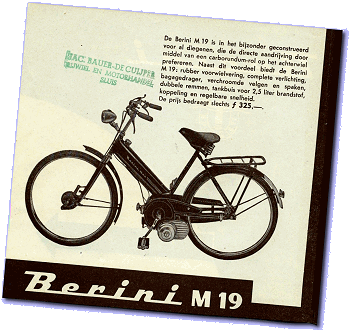

1952, while Berini now presented an M19 ‘Cyclestar’

as an under-bottom-bracket roller-drive machine. Later M19s

evolved a study ‘tank-frame’ design, which further

developed to a central engine mounting arrangement for the new

50cc Pluvier moped engine,

which was launched in Holland as the original Berini Model 21 in

1954.

The British Cyclemaster followed suit, and increased

engine capacity to 32cc in

1952, while Berini now presented an M19 ‘Cyclestar’

as an under-bottom-bracket roller-drive machine. Later M19s

evolved a study ‘tank-frame’ design, which further

developed to a central engine mounting arrangement for the new

50cc Pluvier moped engine,

which was launched in Holland as the original Berini Model 21 in

1954.

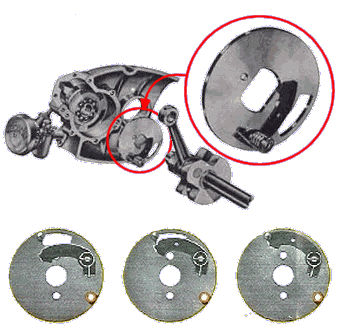

The M21 Pluvier engine was clearly a larger derivation of the original DKW concept, complete with rotary inlet disc-valve, manual clutch, and single-speed drive.

By 1954 however, the British cyclemotor boom was proving to be on the decline—sales were already being lost to the growing popularity of new mopeds, and a greater disposable income meant the customers could afford more than a humble cyclemotor.

Cyclemaster delisted the Berini M13 cyclemotor kit in the UK during 1954, deciding upon an ‘If you can’t beat them, join them’ approach, and adopted a new plan to recycle their cyclemotor into a moped!

Norman at Ashford in Kent was contracted to design and manufacture a frame, and the new Norman Cyclemate moped was launched on the Cyclemaster stand 126 at the 1954 Earls Court Motor Cycle Show. Cyclemaster Ltd separated from EMI during 1955, relocating both its manufacturing operation and offices to Tudor Works in Chertsey Road, Byfleet, Weybridge, Surrey, and in the spring decided to further explore the moped market by buying in trial examples of the early tubular, 5-pint tank-in-frame Berini M21 moped, quoted at a rating of 1.8bhp @ 4,500rpm, which reportedly tested at 35mph on the flat and up to 40mph downhill.

Though samples of this early M21 model were presented in motor cycling press releases of the time, there is no evidence that any examples were actually released onto the UK market before the original Berini M21 tubular frame 5-pint tank model was developed into a press-formed frame version with larger 1½ gallon tank.

Cyclemaster Ltd formally

listed the new M21 De Luxe model as available for UK sales in October 1955, while back in

the Netherlands, new legislation was on the move to regulate the

speed of mopeds to 40km/h from 1956 onwards. Since

Dutch mopeds carried no registration marking, this speed

restriction had to be enforced by imposing technical restraints

upon the moped manufacturers, most of which throttled down

cylinder porting and carburettors. Pluvier however devised

its own ‘Speed-O-Matic’ trick for limiting M21

performance, where a spring-loaded shutter on the rotary valve

closed the inlet port at exactly 40km/h, while still allowing full

engine power to remain available below 38km/h. Because the system

reduced the rev limit of the engine to some 4,000rpm, the given power of

Speed-O-Matic restricted motors was quoted down to

1.7bhp.

Cyclemaster Ltd formally

listed the new M21 De Luxe model as available for UK sales in October 1955, while back in

the Netherlands, new legislation was on the move to regulate the

speed of mopeds to 40km/h from 1956 onwards. Since

Dutch mopeds carried no registration marking, this speed

restriction had to be enforced by imposing technical restraints

upon the moped manufacturers, most of which throttled down

cylinder porting and carburettors. Pluvier however devised

its own ‘Speed-O-Matic’ trick for limiting M21

performance, where a spring-loaded shutter on the rotary valve

closed the inlet port at exactly 40km/h, while still allowing full

engine power to remain available below 38km/h. Because the system

reduced the rev limit of the engine to some 4,000rpm, the given power of

Speed-O-Matic restricted motors was quoted down to

1.7bhp.

There don’t appear to be any references regarding Speed-O-Matic restricted M21 models being sold into the British market, but quoted power ratings seemed to vary from 1957 onwards, some stating 1.7bhp @ 4,800rpm, while others printed 1.8bhp @ 4,800rpm, but UK road-testers now didn’t seem to report over 29mph (compared with 34mph in previous road tests)—so form your own conclusion.

Our featured Berini M21 De Luxe confusingly wears a

re-issued 1964 B-registration plate as a result of some early

number transfer, though its dating is estimated as circa

1957. Might this be a Speed-O-Matic restricted model?

We don’t really know…

Our featured Berini M21 De Luxe confusingly wears a

re-issued 1964 B-registration plate as a result of some early

number transfer, though its dating is estimated as circa

1957. Might this be a Speed-O-Matic restricted model?

We don’t really know…

The Pluvier engine features a horizontal cast iron cylinder and alloy head, with single-speed drive and a manual grip-lock clutch.

The rigid frame has a telescopic fork set, with the stylish 1½ gallon pressed-steel fuel tank sculpted into the lower frame & engine mounting bracket. A Denfeld rubber saddle tops the seat post, and the tubular rear carrier with parcel clip was fitted as standard equipment.

The wheels would have originally carried 2.25 × 20 tyres on Westwood pattern rims, but these tyres are not so easy to get now, so the wheels are now re-laced with new rims to fit 600 × 50B whitewall tyres instead.

Both drive and pedal chains are unusually arranged on the same right-hand side (like the Raleigh RM1, except that the Berini was built first).

The lever fuel tap switches down for on, and might have a reserve, but is fitted in the wrong orientation to be able to turn the lever round any further as it fouls the crankcase.

The disc-valve induction is fed from a 12mm Encarwi carburettor, forward facing with a

‘shield’ over the intake. For starting,

there’s a trigger latch on the throttle, and the twist-grip

clicks forward to ‘choke’ position, raising the

needle within the air slide to enrich the air/fuel mixture.

The disc-valve induction is fed from a 12mm Encarwi carburettor, forward facing with a

‘shield’ over the intake. For starting,

there’s a trigger latch on the throttle, and the twist-grip

clicks forward to ‘choke’ position, raising the

needle within the air slide to enrich the air/fuel mixture.

The motor fires up within a couple of spins of the pedals, then nudge off the rear stand which swings up behind the rear mudguard with a spring-back action as you roll the bike forward, but best to just give that a little secure nudge with your foot to make sure it’s fully up, since we really don’t need the added excitement of that grounding on a corner.

With M21 having a back pedal brake, the simple Magura controls comprise just throttle & front brake and grip-lock clutch lever, presenting a tidy and uncluttered handlebar set with no wiring and only three control cables—less is more. You can then ride along and admire the purity of the curvaceous handlebar form, while the chrome plated short-barrel silencer produces a crisp popping note at low revs that evens out to a mellow drone under load.

This is all very pleasant and civilised!

The benefit of disc-valve induction demonstrated itself capably against inclines, despatching inclines with capable torque and giving little suggestion that the engine would be likely to need any assistance.

Exchanges with our pacer quickly established that our M21 had a slow VDO speedometer set … our on-flat speed paced at 30mph, but the speedo only indicated 25.

The old-fashioned ‘North Road’ pull-back style handlebars presented a naturally upright riding posture, which meant it wasn’t so easy to adopt a crouch position, though this didn’t appear necessary because the motor seemed to get up to top revs easily enough on the downhill run, which paced at 35mph, though the speedo again indicated 5mph slower.

Speed-O-Matic mechanism

There didn’t feel to be any definable ‘speed clipping’ effect to the performance, so we presumed our test bike might have been a 1956 produced machine, and maybe a pre-Speed-O-Matic limited model, but without experience in feel of how smoothly the restrictor might work, it’s difficult to be sure without taking the engine apart.

The back-pedal coaster type hub brake worked surprisingly well. We’ve often criticised the dismal performance of Perry coaster brakes on mopeds in the past, but this continental equivalent proved appreciably better.

The continental Radrone headlamp with a simple off–on switch on top of the shell, produced only a dim light, though we suspect the bulb wattages are probably not correctly rated. The Lucas rear lamp unit would have been the correct fitment for the British market due to the legal requirement to illuminate the back number plate.

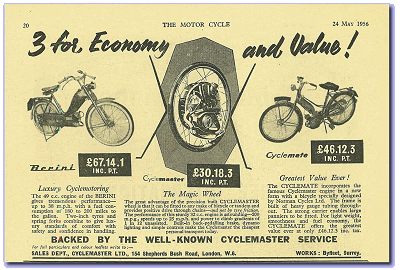

Early in 1956 the Cyclemaster sales office moved back to London, at 154 Shepherds Bush Road, as the dwindling cyclemotor market continued to ebb away, and by 1957 the Cyclemaster had only another five makes of cyclemotors to compete with on the British market.

While the Cyclemate certainly remained among the most price-competitive machines available in the day, at just 32cc it was technically the smallest example in the moped category, and certainly among the lowest powered and slowest of 32 different makes of moped on sale at the time—and pure cost alone was not necessarily the main factor on which many customers were basing their choice.

Cyclemaster Ltd was now desperately spreading its business to include factored sales of the Berini M21 and M22 mopeds and Piatti scooter in its range of machines.

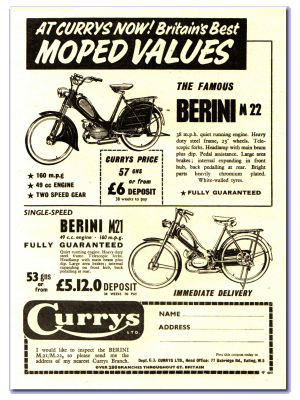

Cyclemaster had been acting as agents selling Berini

into the UK up to 1957, but by June the Berini licence was taken

over by Curry’s.

Cyclemaster had been acting as agents selling Berini

into the UK up to 1957, but by June the Berini licence was taken

over by Curry’s.

In August 1957, the Shepherds Bush offices closed, and functions consolidated back to the Tudor Works address in a belated attempt to reduce costs.

Tough times got tougher for Cyclemaster as a creditors meeting was called in December 1957, so it’s a possibility that with bankruptcy looming, Cyclemaster might have sold off its stock and the Berini licence to Curry’s in an attempt to raise cash. Cyclemaster had done deals with Curry’s before, since Cyclemates were sold through Curry’s.

A rescue package was proposed, but by January 1958, the business had entered into voluntary liquidation.

A new company called Planloc Engineering was formed in March 1958 to purchase the remains of the Cyclemaster business and resume production of the Cyclemaster, Cyclemate, and Piatti scooter from Tudor Works.

Manufacture of the Piatti scooter effectively concluded toward the end of 1958 as the remaining stock of assembly components were built out, though poor sales of this machine meant that these last completed scooters would still be trickling out of the factory for some while after production actually ended.

Curry’s reintroduced the Berini M13

cyclemotor to the UK in 1958

though this time it was sold as a complete machine ready-attached

to a cycle.

Curry’s reintroduced the Berini M13

cyclemotor to the UK in 1958

though this time it was sold as a complete machine ready-attached

to a cycle.

The business structures of Berini and Pluvier seemed intertwined, which led to some ‘complications’ further down the line. While Pluvier was established as a manufacturing concern by HNG to produce engines for Bernhard Neumann, Rinus Bruynzeel and Nico Groenerdijke, Berini developed more as marketing organisation selling complete machines under its brand.

Due to disagreement between former shareholders Hart, Nibbrig & Greeve, and Pluvier Motorenfabriek, the Berini mopeds in 1956 also became marketed under the Pluvier name, and Pluvier also sold their motors to other moped builders.

Despite the popularity of its products into the early 1960s, poor marketing and mismanagement took Berini’s business and Pluvier Motorenfabriek to bankruptcy in 1964.

The Berini name was purchased by the Anker mining company who resumed manufacture with Gazelle frames using mainly Anker–Laura motors with some Tomos and revived Pluvier engines.

In 1981, Berini was sold on to South Korean ownership, who used the brand for Berini mopeds in the Korean home market for 15 years. The Berini name returned to Europe again in 1998 under the ownership of the Alblas company of Rotterdam, who sticker-branded batches of imported Indian-built mopeds fitted with Anker M-48 engines, since which time it markets a new generation of Chinese-built Berini branded scooters.