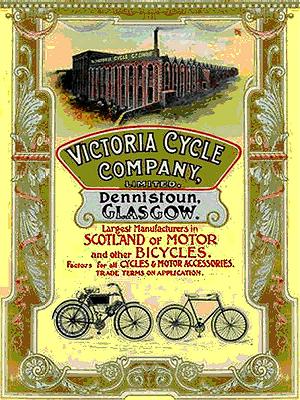

Completely unrelated to the UK’s Victoria Cycle

Company Ltd. of Dennistoun at Glasgow, circa 1897–1926, the

German Victoria Company founded its business in 1886 as a bicycle

builder in the medieval city of Nürnberg, and completing its

1,000th cycle within two years of production.

Completely unrelated to the UK’s Victoria Cycle

Company Ltd. of Dennistoun at Glasgow, circa 1897–1926, the

German Victoria Company founded its business in 1886 as a bicycle

builder in the medieval city of Nürnberg, and completing its

1,000th cycle within two years of production.

Victoria began to expand into the field of motorised bicycles and motor cycles around 1900, fitting a variety of different power units from various sources, including Cudel motors, Belgian FN, German Columbus and Fafnir engines. During the Great War, Victoria is vaguely reported as turning to the production of ‘defence materials’, and as soon as was possible following the armistice, returning to the manufacture of civilian motor cycles in 1919 and resuming sales to the public in 1920 with the fitment of BMW M2-B15, 494cc side-valve engines in the new KR1 model.

In 1923, Martin Stolle came from BMW to develop an OHV ‘boxer’ engine for Victoria’s next KR-II motor cycle, which was introduced a year before BMW’s equivalent ‘boxer’ model appeared. The first German supercharged motors were built at Victoria by engineer Steinlein in 1925, and the company went racing, with Adolf Brudes setting a new German speed record of 166km/h on a 497cc supercharged Victoria in 1926. In 1928, 200cc SV and 350cc OHV engines were imported to establish a selection of smaller Victoria machines and, from 1930 on, 500cc OHV and SV English-built Sturmey–Archer engines were brought in to extend the middle capacity range. 1931–32 Victoria won the European Mountain ‘Bergmeisterschaft’ Championship in the 600cc class, following which the new boxer model was immediately named the ‘Bergmeister’ Mountain Champion.

In 1934 the recently elected National Socialist government forbade the import of foreign components, which concluded Victoria’s use of Sturmey–Archer engines, requiring Victoria to develop a new selection of models using their own motor designs and some proprietary Columbus engines. Richard Küchen designed a new motor cycle range for Victoria in 1937, with Aero, Lux, Fix, and Pionier models. Production of civilian vehicles practically ended in 1939 when the German army placed an order for 4,000 Pionier models with special military equipment fittings specified. By the time World War II ended, Victoria’s factory buildings lay in ruins, a bombed out shell among a sea of wreckage.

After 60 years climbing the ladder of progress, everything had been lost in the legacy of fascism, and now the company would have to start from the bottom rung again.

Victoria reportedly resumed production in 1946 with the FM38cc 1bhp auxiliary engine for bicycles. This little attachment motor was probably based on an earlier pre-war design that became a more practical proposition in the days of post-war austerity with a demand for cheap and economical transport. The engine however, must have been produced from some other adopted location, since the devastated hulk of the Victoria factory laid among a pile of rubble, remaining derelict until 1948, when operations began to clear the site and recover whatever might be salvaged.

In 1949 Victoria resumed manufacture of the pre-war KR25 Aero motor cycle model, which was up-rated to a new telescopic front fork in 1950, joined by Vicky-I + Vicky-II lightweights using the FM38 bicycle engine, and a new V99cc BL-Fix model. By the end of the year it looked as if Victoria was on the road to recovery from its wartime setbacks as production of the KR25 Aero was reported at 14,000 a year, and the model was further equipped with Jurisch plunger rear suspension from 1951.

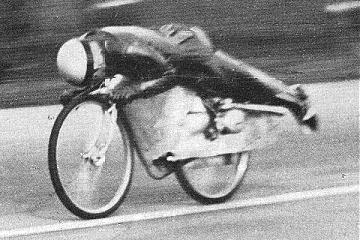

In 1951 Georg Dotterweich set a new world speed record with

a streamlined 38cc Vicky

along the Munich–Ingolstadt Autobahn at a speed of

79km/h (49mph). While the cycle frame was

clad with streamlined lightweight alloy fairings, the motor was

claimed to be of ‘standard specification’ (which

might seem highly unlikely for such a small and low compression

engine to pull the required drive ratio and revs along the flat

to attain that kind of speed). Richard Küchen

subsequently reappeared in later despatches in connection with

the Küchen 38S cyclemotor engine, which Gerd Siefert design

was also adopted by Lettington Eng/Cyc-Auto as the Bantamoto

cyclemotor, and sold by A. Gatto 206–212 Garratt Lane,

Earlsfield, London SW18.

In 1951 Georg Dotterweich set a new world speed record with

a streamlined 38cc Vicky

along the Munich–Ingolstadt Autobahn at a speed of

79km/h (49mph). While the cycle frame was

clad with streamlined lightweight alloy fairings, the motor was

claimed to be of ‘standard specification’ (which

might seem highly unlikely for such a small and low compression

engine to pull the required drive ratio and revs along the flat

to attain that kind of speed). Richard Küchen

subsequently reappeared in later despatches in connection with

the Küchen 38S cyclemotor engine, which Gerd Siefert design

was also adopted by Lettington Eng/Cyc-Auto as the Bantamoto

cyclemotor, and sold by A. Gatto 206–212 Garratt Lane,

Earlsfield, London SW18.

In 1953 Victoria developed its popular models further with the latest KR26 Aero, and expanded its range with the new Küchen designed V35 Bergmeister, being a 350cc OHV transverse V-twin producing 21bhp, and having shaft-drive to the rear wheel.

In 1954 Victoria introduced the Vicky moped, designated

model III and employing a new model M50 48cc two-stroke engine. The Vicky

III was imported into Great Britain from January 1956, and also

marketed across Scandinavia as the MS50.

In 1954 Victoria introduced the Vicky moped, designated

model III and employing a new model M50 48cc two-stroke engine. The Vicky

III was imported into Great Britain from January 1956, and also

marketed across Scandinavia as the MS50.

1955 brought the new Victoria Peggy motor scooter with a fan-cooled, 200cc two-stroke engine and electric starting. The same year, Victoria also presented the over-complicated and consequently expensive KR21 ‘Swing’ motor cycle. It was a bloated and overpriced technological indulgence with a ridiculous electric push-button gear selection system that found little more than novelty appeal. Neither vehicle was commercially viable for the business, requiring significant development and investment to produce, while being the wrong products at the wrong time, just when the market was starting to contract.

1957 saw a new Vicky IV moped with model M51 engine employing the same top-end, barrel, piston and 8:1 compression cylinder head as the preceding M50 motor, still rated at the same 1.75ps (bhp) output, but fitted to a redesigned motor bottom-end. In defiance of the new M51 engine type, the M50 motor remained in production in the continuing Vicky III model to offer a low-cost moped option. The Victoria Vicky models are characterised by quite individual Teutonic styling. They manage to achieve a very ‘distinctive’ look about them, which is somewhat different and interesting, and many people find strangely appealing in an eccentric and unique way.

Our feature machine is one of the first season

Vicky IV models, dated 1957, with two-speed hand change

gears.

Our feature machine is one of the first season

Vicky IV models, dated 1957, with two-speed hand change

gears.

Wheels and tyres are 2.00–19 (23") Veith Extra Prima (original German rubber) on Schurman alloy rims, and Victoria’s own finely cast full-width alloy hubs. There’s quite an alloy theme going on with the Vicky, since it has a cast alloy silencer ending in a quaint chrome plated tail-piece with a peashooter pipe outlet. The fuel tank is seemingly ‘bumpered’ with formed alloy badge pressings, however these actually function as tidy cable guides, so they have a practical use as well as giving the frame a stylish look.

You can’t see Vicky’s carburettor or fuel tap at all, there’s only a rotary tap lever poking through a small hole on the right hand side of the frame just behind the cylinder. Turn 90° for on, and 180° for reserve. With the carburettor completely obscured within the frame, there’s probably going to be some remote means of either choke control or flooding to start. A small trigger under the twist-grip obviously works the decompresser, so nothing else on the handlebar set … Ah! Crouching down to look around the frame by the motor, there seems to be a small lever underneath the lifting handle in the crook of the frame? With only a single screw seemingly holding this casting on, we muster a driver to investigate. Removing the handle plate, the rocking lever inside simply presses down the choke shutter, which will lift off automatically once the throttle is opened. Within the cavity is a 14mm Bing carburetter (quite a large size for a moped of this period), air filter, a completely inaccessible fuel tap up inside a pocket within the frame, and a few wires connecting to the engine.

Grip the lifting handle and your forward finger triggers on

the choke. Decompress (or the clutch may slip), then press

on a pedal to get the motor spinning, and drop the decompresser

trigger to get the motor to fire. It takes a few attempts

to get the timing right for releasing the decompresser trigger at

the optimum moment, then the motor fires right up, so it was

probably us getting the technique wrong rather than the motor

failing to start. We run the engine a little to clear the

choke, and then nudge off the stand to prepare to set off …

but the stand scrapes along the ground as we wheel out of the

workshop. What now? Isn’t the stand spring

working? No, it doesn’t seem to have one, and the

stand just dangles limply beneath. Have a closer look, and

there’s a clip beneath the frame, so this is intentionally

one of those stands that have to clip up into place by lifting

the stand on your foot. It takes quite a firm push to get

the stand to lock in its latch. Once up in place, the catch

is quite secure, but it’s easy to see why this idea

subsequently failed in favour of the sprung stand.

Grip the lifting handle and your forward finger triggers on

the choke. Decompress (or the clutch may slip), then press

on a pedal to get the motor spinning, and drop the decompresser

trigger to get the motor to fire. It takes a few attempts

to get the timing right for releasing the decompresser trigger at

the optimum moment, then the motor fires right up, so it was

probably us getting the technique wrong rather than the motor

failing to start. We run the engine a little to clear the

choke, and then nudge off the stand to prepare to set off …

but the stand scrapes along the ground as we wheel out of the

workshop. What now? Isn’t the stand spring

working? No, it doesn’t seem to have one, and the

stand just dangles limply beneath. Have a closer look, and

there’s a clip beneath the frame, so this is intentionally

one of those stands that have to clip up into place by lifting

the stand on your foot. It takes quite a firm push to get

the stand to lock in its latch. Once up in place, the catch

is quite secure, but it’s easy to see why this idea

subsequently failed in favour of the sprung stand.

Pull in the clutch lever, and twist the hand-shift back for first, which engages with a bit of a clunk because the clutch feels to drag a little, so we feed in some throttle and pull smartly away. Initial take-off is strong and easy since the M51 engine delivers surprisingly good torque from quite low revs. Clutch back in, twist forward into second, and the torque still pulls the bike on well in its higher gear … and there’s not even the faintest flicker of life from the 45mph VDO speedometer, which clearly doesn’t work at all, so we’re reliant on our pacer again. 30mph is generally attainable along the flat in an upright position in still air, though you can coax it up to 32 by adopting a crouch, or sometimes a little more if aided by a tailwind. The downhill run clocked off at 38mph by the pace vehicle, with the engine handling these heady revs well enough, though it didn’t feel in naturally happy territory. Our Vicky tackled the following uphill most enthusiastically, showing good torque against the ascent, confidently conquering the crest at 25mph, and strongly pulling back up to pace again once over the crest. A really good uphill account for a moped of this age!

Both the front, and cable operated back-pedal rear brake

proved very good, and delivered effective stopping power beyond

the bike’s performance. General handling was good,

the suspension proving firm at both ends. Springing in the

rear units seemed fairly strong, and they didn’t surrender

much movement on the swing-arm. The leading-link front

‘suspension’ was more of a term than a reality,

comprised of Metalastic torsion bushes, which actually proved

more like vibration damping than actual movement. The

rubber covered Wittkop saddle was getting tired and perished

because of its age, so the seat was getting quite sad and saggy,

and wasn’t too good in the comfort stakes. New

Wittkop covers are still available (at extortionate cost), and

this original seat could certainly be revived.

Both the front, and cable operated back-pedal rear brake

proved very good, and delivered effective stopping power beyond

the bike’s performance. General handling was good,

the suspension proving firm at both ends. Springing in the

rear units seemed fairly strong, and they didn’t surrender

much movement on the swing-arm. The leading-link front

‘suspension’ was more of a term than a reality,

comprised of Metalastic torsion bushes, which actually proved

more like vibration damping than actual movement. The

rubber covered Wittkop saddle was getting tired and perished

because of its age, so the seat was getting quite sad and saggy,

and wasn’t too good in the comfort stakes. New

Wittkop covers are still available (at extortionate cost), and

this original seat could certainly be revived.

Following our ride, we thought we’d try the lights … turn the lighting switch clockwise … and the engine stopped! ’Ello, ’ello—what’s going on ’ere? Restart the bike, turn the switch to the right, and sure enough the engine cuts out … but turn it to the left, and the lights come on! Right position is obviously wired as a cut-out, which seems a little unusual for a bike equipped with a decompresser, as every manufacturer we can recall has never equipped an electrical cut-out when a decompresser is fitted, you always stop on the decompresser—but not it seems, for Victoria!

The Hella headlamp actually seemed to deliver a reasonable light in both beam and dip, though the Hella tail lamp was little more than a dull glowing red ember from some miserable festoon bulb hiding toward the bottom of its casing. The Noris horn is fixed off the right-hand rear spring unit top mounting almost like an afterthought! This appears to be the correct factory position, but seems to be strangely at odds with Victoria’s tidy design. The horn croaks like an old frog at tick-over, rising to an irritated buzz as the revs are tweaked up. Continuing the proprietary fittings theme, the controls are all Magura, and a Niemann steering lock is fitted into the headstock. There’s a pressed-steel rear carrier with toolbox at the back, and the contained toolkit rattled annoyingly throughout the test ride at every ripple in the road.

The Vicky steering headset looks like some culinary implement from a Gothic horror story! It’s difficult to understand what may have inspired the brassiere shaped inverted chrome ashtrays that fill sockets for an optional clock to the left, and optional something-else to the right, with the speedometer above and in the middle. Every time you look down to check the speed, you wonder, what was Victoria thinking when it came up with this arrangement? Vicky is odd, interesting, quirky … you may like it, but Teutonic opera may not be quite to everyone’s taste.

The year 1957 had also found Victoria presenting a new KR17 motor cycle model with a 175cc OHV four-stroke engine, but practically the whole bike was imported from Parilla in Italy. For Victoria to be resorting to factoring was a sign that things weren’t going so well in their motor cycle business. This became the last Victoria-branded motor cycle, and was quickly de-listed during the same year, after which the company remained exclusively with moped and lightweight scooter production.

In 1958, Victoria merged with DKW and Express Werke AG, forming the Zweirad Union, which maintained the Victoria name on its continued Vicky mopeds and small motor scooters. The Express brand was discontinued in 1959, while introduction of the Victoria Vicky Luxus model in 1959 rationalised all earlier versions thereafter, so Vicky III-N, IV two-speed & IV three-speed were de-listed from August. The Victoria Luxus continued to December 1962, when replaced by other standard Zweirad Union—branded products with proprietary Sachs engines, which were also sold with DKW badges. The Fichtel & Sachs company bought out the German Hercules company in 1963, and further took control of the Zweirad Union in 1966. The DKW brand was merged with Hercules, while Victoria-badged products disappeared within the rationalisation.