Louis M Cazenave was born to a working class family at Belin–Béliet, Gironde province, France, in 1883, and found his first job at 14 years old, labouring in a sawmill. He worked through several other positions, including a locksmith’s assistant and, showing strong mechanical aptitude, progressed to attending the maintenance and repair of steam engines.

In 1901 Louis began renting a small lock-up shop to sell and repair bicycles then, helped by his cousin, soon managed to set up a bigger workshop, hiring 15 workers to start assembly and sales of bicycles.

Painted parts were initially sent out to Bordeaux for coating but, within a few years, Cazenave had managed to establish his own enamelling workshop.

He also bought a house in the town, since the businesses were operating in Belin, running the workshops and a store selling firearms, sewing machines and cookers to mainly local customers in the immediate agricultural region.

In 1905, Louis Cazenave married Fernande Herreyre; they had their first son, Guy, in 1906, at which the home and workshop premises seemed to be becoming too small for the expanding business and family, so Louis decided to buy an old glassworks of around 600m² as a new location for the workshops.

During the First World War, Cazenave’s works were turned over to the making of ammunition, requiring the establishment of a foundry to cast shell casings, and a sawmill for making boxes for the packing and shipping of munitions.

His second son, Frank, was born in 1917 and, following the armistice, Cazenave returned to its core business of building bicycles. The foundry was redirected towards producing iron hardware and engine component castings for contract customers, while the sawmill was turned to the conversion of building timbers, floorboards, agricultural carts, timber wagons, rolling stock trailers and tanker frames.

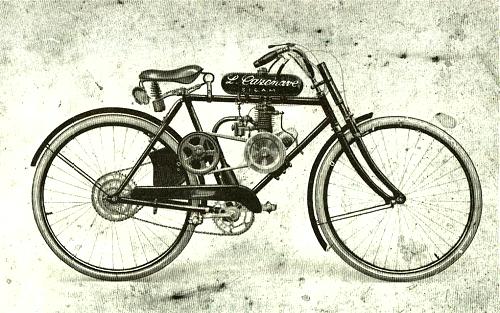

The family business continued expanding and Louis’s sister joined in 1919 to work in the offices and, in 1925, now at the age of 19, his eldest son Guy started work in the company. Around this time Louis was also developing an interest in motorised vehicles, producing his first ‘Cazenavette’ motor cycle around 1925, which seemed to be based on a Motobécane pattern. Probably not unexpectedly, this first primitive Cazenave motor cycle was more akin to a cyclemotor with an engine mounted into the diamond of a bicycle frame.

After completing his education, younger son Frank also joined the business in the later 1930s.

During WWII the Gironde region came under Axis control, and Cazenave agreed to work for the German occupying forces in order to keep the factory running, while Frank left to become an Army pilot, and in 1942 joined the ‘Free France’ movement.

After the war, Cazenave returned to its former businesses and manufacturing bicycles.

Among 24 bicycles displayed on their stand at the Paris Salon in October 1950, Cazenave also presented a cyclemotor with VAP4 engine and side-panel covers.

By 1954 the Cazenave businesses were employing some 700 workers across their much-expanded complex of factories; Booming demand for economical motorised transport over recent years was promising new opportunities, but the company was only just about to enter significant motorised two-wheeler production by introduction of a selection of lightweight models. Cazenave presented three motor cycles, a 200cc two-stroke, 125cc two-stroke and 125cc four-stroke, along with an initial range of seven mopeds.

Two of these mopeds (Model 35 rigid, Model 38 tele-fork) had a mono-tube frame and a roller-drive power unit (allegedly of their own construction), mounted below the pedals. All the others had a tubular frame (of a similar style to the Mobylette AV3). Three were powered by VAP-55 motors: 415 rigid, no clutch; 420 rigid, auto clutch; 421 tele-fork, auto-clutch. The other two were 545 with VAP-B and 546 with VAP-G.

The following year (1955) a 98cc motor cycle and a 98cc large-wheel Belina scooter joined the range, both powered by Mistral two-speed motors.

Within just a couple of years the range of motorised vehicles had increased dramatically, now including motor cycles, scooters, and even small cars using AMC, Peugeot, Ultima, Villiers and Ydral engines, while mopeds were mainly being assembled using VAP and AML–Motul Lavalette engines.

In October 1957 the 61-33 model appeared with a beam frame, VAP-57 engine and rear swinging arm controlled by a single spring concealed in the copious rear mudguard.

By 1958, all the VAP-55 models were now being re-equipped with VAP-57 or Lavalette engines, the VAP-B had gone but the VAP-G continued. The Cazenave range was already becoming a bewildering selection of machines with anonymous model references, and confusion was only further compounded by addition of another five more VAP-57 monotube models. The 48-60 was a new machine, similar to the 61-33 with the same rear suspension but a pressed-steel frame, while the 48-50 seemed the same, but with a rigid rear. 48-76 was like the 48-60 but with a three-speed Sachs engine. The 1958 mono-tube range went from a bottom-of-range model 410, to top-of-range full suspension 311.

Aged 75, Louis M Cazenave died in 1958, leaving his sons to continue running the family business.

With an emerging fashion for sports-styled lightweights, in 1959, a 220 model sports moped was added to the range. Despite its ‘sporty’ looks with twin exhausts, this still used the not-so-sporty VAP-57 engine. A 230 model employed the same cycle frame, except being installed with a Ilo engine. There was also a sports motor cycle with a 112cc Uniméca engine (Uniméca was previously Monet–Goyon and the engine was built under licence from Villiers).

Approaching the end of the decade, increasing social prosperity and the growing popularity of small cars against declining sales of mopeds and scooters was beginning to compromise the whole French motor cycle industry in much the same manner as the in other European countries. The British, German, and Italian motor cycle industries were all experiencing similar declines towards the tail of the 1950s, and the French home market was no different, resulting in close co-operation between a number of these national businesses, and culminating in a series of large-scale mergers and takeovers as the industry frantically re-structured in a desperate effort to survive.

Cazenave & Uniméca had just merged but, in 1960, this union was taken over by Gutbrod–Motostandard and re-formed into Groupe CDGJ, comprising Cazenave, Dilecta, Gitane & Jeunet–Captivante.

Branding rationalisation saw the Dilecta badge disappear after 1961.

French-built Cazenave mopeds were only briefly imported into the UK between December 1959 and August 1962 by UK concessionaires Layford (Automotive) Ltd, of King Street, Hammersmith, London W6. Two models were offered: initially the 411 with a rigid bicycle-type front fork and brakes, and a 421, which featured a telescopic front fork and full width hubs. Both models were powered by 48cc VAP engines and had automatic-clutch transmission, the former selling for under £40.

Two Cazenave mopeds later listed, described both with rigid monotube frames, as model 421 now appearing with a rigid fork, and model 422 with a tele-fork. Cazenave serial designations can sometimes appear contradictory with other specification descriptions, so there might have been some reshuffle of model numbers at some point as 421 had previously been represented as top-of-the-AV3-style-range.

Both the 421 and 422 mounted their fuel tanks beneath the saddle, and were seemingly not the same style of machine originally road-tested by the some of the British motor cycling press.

Positive identification of Cazenave mopeds can be particularly challenging; there is such an extensive range of machines, and so many model serials only appear listed by some vague description—which may not necessarily be accurate anyway. Trying to figure out and identify all the respective models is practically impossible since there doesn’t appear to have been any comprehensive reference compiled.

All of these 411, 421 and 422 models had fuel tanks behind the saddle stem, while our test machine features a fore tank, so doesn’t appear to be any type officially imported to the UK, and because of the difficulty in identification—we really can’t be sure quite what model it may be!

Our mount is an attractive and stylish little machine, arousing some impression of character and quality, appearing slightly less ‘utility’ than Automoto and Auto-VAP powered mopeds we’ve experienced in the past. The rigid-rear frame is sprung up front with telescopic forks, and mounts a cylindrical toolbox beneath the Perjohn sprung single-saddle, while full-width cast aluminium Leleu 80mm hubs are laced into 19-inch AVA Inoxy rims, and shod with 23×2 tyres.

There are some really nice touches adding to the overall impression of better quality fittings on this machine: a SELF alloy shell headlamp with Deco style ornate lens clamp, pierced latticework of the Nervex pressed-steel rear carrier, and elegance of the Saker throttle twist-grip and slender handlebar levers. Having the lever mounting brackets welded to the handlebars really ‘cleans up’ this purpose-made bar assembly from the clutter of having separate fittings with clamps, so looks both smart and tidy.

While studying the bike, there appear lots of obviously genuine detail aspects and original features that just look like nice quality touches, and convince us that this (unknown model) was probably classed above the utility types.

Its frame number of T.5259 doesn’t give us much of a clue either…

The belt flywheel however, doesn’t appear to be what we’d typically expect to find with a late 1950s’/early 1960s’ VAP engine. It has a sliding plastic thumb button to engage–disengage the motor & pedal drive. Tap the belt flywheel and it’s made of plastic! We think the original period VAP flywheel would have been made from cast zinc with a rotary engagement mechanism in the centre, while this flywheel appears to be more like a Peugeot Vogue of the late ’70s or early ’80s, so we feel there’s been some transplanting gone on here, presumably because of ‘issues’ with the original equipment.

The original VAP flywheels were 200mm diameter, but this Peugeot flywheel measures 220mm, which means the drive belt must have also been changed to accommodate the extra length, so this aspect alone will gear down the drive ratio by 10% and will almost certainly influence impressions of the road-test aspect.

The lighting switch is capped with an aluminium SELF closing plate while the headlamp still wears its original fitted SELF speedometer blanking plate and the lens mounting two small 6V, 6W MES beam–dip bulbs that are obviously not going to cast much light in the darkness. The VAP Magnéclair lighting generators were only fitted with low output ‘marker’ coils, with only just enough Watts to be seen by, but not enough Watts to actually see by.

The pedal blocks are marked Éclair, which sounds as if they could be original equipment, but let’s hope they’re not made of chocolate…

Starting a VAP is a familiar procedure to us, turn on the fuel tap at bottom right of the tank, click down the choke latch on the Gurtner D12 carburettor (which will automatically snap-release when the throttle is opened), twist the throttle forward to decompress, off the stand, and pedal up the road with the valve venting to get the engine turning. Because of ratchet drive to the clutch, the VAP motor will turn right away and doesn’t give the rider opportunity to build up any momentum, but blimey—this seems a little harder work than we remember! It appears the reduced drive ratio from the flywheel change is working against us in this phase, so prospects of ‘kick-starting’ this machine on the stand would probably seem to be off the menu!

Now appreciating the extra effort required to start our machine, we’re better prepared this time, and stand firmly on the pedals to spin the motor, which burbles into life. We coast gently along the road to coax the engine into consistent running before opening the throttle to unlatch the choke. The carburetter intake gratefully sucks a rush of air into its venturi with a flat roar as the motor struggles against the initial take-off, so we give a small boost on the pedals to help it along, and ease gently away with the pace vehicle tracking our progress.

Flat cruising builds steadily up to 25mph on full throttle as the engine warms up, and we manage to hit a best on flat of 27mph in a crouch with a tailwind.

Our downhill run peaks at 33, but fades to a miserable 13mph cresting the rise on the following climb, which we thought was a particularly poor showing considering the lower gearing, however the motor began to feel a bit down on power a little further up the road, then shortly petered out with an obstructed fuel supply, so the uphill aspect might not have been wholly representative.

The bike generally handled nicely, rode well, and stopped well. The lights were dull and inadequate, though fairly typical of what we expected from the pitiful Magnéclair ‘marker’ lighting coil, which was only specified to drive a 6V × 1A (3W) headlamp and 12V × 0.5A rear bulb.

The impression was that our Cazenave moped had not been particularly improved by its flywheel/gearing reduction, and would almost certainly have started easier and performed better with the original equipment.

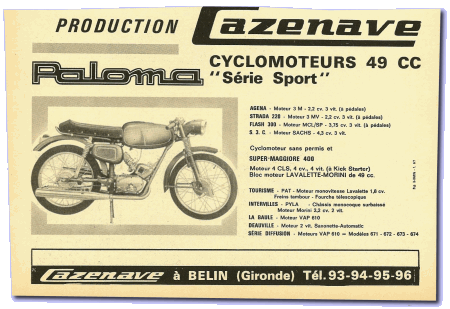

On 6th July 1964, the newspaper l’Avenir d’Arcachon announced the merger of Cazenave with Paloma and VAP (which had recently lost the support of its ABG parent group), and all production subsequently moved to the Cazenave manufacturing site at Belin. Cazenave’s intention was probably to secure ongoing Lavalette and VAP engine supplies for its mopeds, but the Paloma brand was also a well-respected cycling name in the marketplace, and would be maintained on badged products after the business absorption.

VAP motors continued to be produced up until the final VAP engine model was sold in the last VéloVAP cyclomoteur when that machine concluded in 1969.

At the height of its activity in the mid-1950s, the Ets Cazenave plant employed some 750 workers and occupied a site of 35 hectares, even including a small ‘working township’ of 130 homes for employees’ families, a co-operative, cinema, canteen, and mutual aid society. After several years of declining production, the difficulties of 1969 led the company to a state of insolvency before the Commercial Court of Bordeaux in 1970.

Even toward the end of 1970, some last desperate efforts were still being made to assemble a new Cazenave-branded sports 50 from mainly imported Italian parts, and using a Morini Franco engine. The initiative seemed to have failed and it’s not clear if any production machines were built and sold.

In 1971, Frank Cazenave left the management of the factory that still bore his name, and the gradual winding down process began with a series of redundancies. Production of Cazenave bicycles ended as the cycle shop closed on 30th August 1971.

Hopeful plans of restoring cycle production in September 1972 came to nought, and the company continued in its steady downward spiral of decline.

At the death of Frank Cazenave on August 9th 1974, it seemed to be a symbolic end of what remained of the family business. At the announcement of new layoffs toward the end of July 1975, sit-in workers occupied the factory up to the end of the year, when police acting under a court order began evicting them.

The factory formally closed in December 1975—an employment tragedy for Belin–Béliet and the surrounding area.

Proposals were made in February 1976 for the Rauad Company to recover operations in the sawmill, and rolling stock works being adopted by Castera Co. to resume production of trailers and semi-trailers in April, re-employing just 42 of the former Cazenave workers at a lower wage.

On 20th April 1984, Trailers Cazenave SA Castera filed for bankruptcy.

Considering that, in 1964, Cazenave had absorbed VAP, Lavalette and Paloma, as two of the major French moped engine and cycle manufacturers, it might seem almost unimaginable that this large and successful company with such a diverse product range could so quickly decline into collapse within just a few more years, but market forces had moved against its major business and left its position vulnerable.

A mighty oak had fallen in the forest.