When IceniCAM goes to 50cc events in Holland, a Kreidler is usually ‘the weapon of choice’ for the fast boys in the Netherlands. While the main body of the run ambles along about 50km/h, these ‘Flying Dutchmen’ go stonking past in the outside lane at 100km/h, to marshal the forward junctions ahead of the group. Solidly-built chassis with proper suspension, chunky alloy wheels with big tyres, all for great handling, fantastic brakes, four, five, sometimes six-speed competition gearboxes, 16 millimetre, 19 millimetre carburettors, Kreidler Floretts are well and truly among the top-gun jet-fighters of the moped world—so when we’re offered one for a feature, you think wow! A chance to run something quick for a change … but all may not be as it may seem … the bike doesn’t go and the workshops have to get it running first, so beware—The Sheep in Wolf’s Clothing.

Earliest engineering references to Kreidler suggest that it may have evolved from a background of wire making, starting around 1888. The company was formally founded in 1903 as Kreidlers Metall- und Drahtwerke (Kreidlers metal and wire factory) at Kornwestheim near Stuttgart, continuing with this work until towards the end of World War Two when the site was damaged among some of the 53 various Allied air raids directed against Stuttgart area targets. By the time the French 5th Armoured Division swept though Stuttgart on 21st April 1945, Kreidler’s wire factory was already ruined.

In 1950, Anton Kreidler re-started a small factory at the old site to begin building motor cycles, commencing with his own 50cc two-stroke moped engine and constructing an un-stylish and heavy industrial frame to put it in. This initial K50 ‘moped’ became available in 1951, except for the fact that despite being 50cc and having pedals, the Kreidler K50 didn’t technically comply with the German moped specification of its time, since at 45 kilogramme it was too heavy to qualify within the maximum 33 kilogramme moped weight requirement of the day, so was classed as a motor cycle.

Despite the weight/classification issue, the K50 sold surprisingly well, earning a reputation for practical indestructibility and ease of operation, becoming popular with ladies apprehensive about operating motor cycles of the time. As it happened, its stout construction wasn’t a bad thing, as many 33 kilogramme mopeds constructed to meet the specification were often too flimsy, and not uncommonly prone to structural failure. The solidly-built K50 Kreidler didn’t suffer the common cycle frame related failures of other makes and still performed well for its size and time, producing 2.2BHP, and capable of exceeding 30mph.

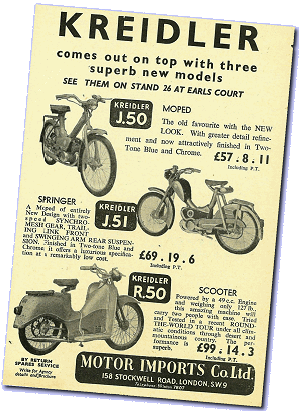

The following Kreidler J50 model of 1953 was more lightly designed to comply as a 33 kilogramme moped, but the on-going weight regulation was proving unpopular with both manufacturers and customers since cycle frame-related failures were common, due to frail construction. There’s going to be some obvious issue when a 20-stone rider thrashes a moped just one quarter of their weight down a pot-holed road … something is going to break, and the inevitable conclusion wasn’t doing the reputation of the German moped manufacturers any good at all. People were getting injured on inadequate machines that couldn’t be improved with solid frames, proper suspension, or good functional brakes because the German moped weight regulation prevented any German-built mopeds from being soundly engineered.

Common sense finally prevailed and the weight specification was withdrawn by 1955, finally allowing all manufacturers to start engineering better constructed mopeds.

In 1956, Kreidler presented the first of its sensational Florett (Foil) model ‘sports’ mopeds with motor cycle style ‘top tank’ and rated 3BHP @ 6,000rpm. It was an immediate success, and Kreidler was looking well poised to be securing future sales at a time when the market conditions were just starting to become difficult.

By the late 1950s, improvements in the standard of living and people’s disposable income led to increasing car sales, but much to the cost of motor cycle sales, which slumped dramatically. While a lot of the smaller German motor cycle and moped manufacturers were going to the wall, Kreidler’s quality reputation and popular styled designs seemed to maintain its sales at a time when even many well-known and long established names were going through very tough times. DKW, the German Hercules brand, Rabenieck, Rixe, Victoria and Zündapp were all resorting to moped manufacture to try and weather the slump but, by 1959, Kreidler was accounting for a third of all German motor cycle sales! Its reputation was soundly based on solid construction, good handling, stylish looks, reliability, and high performance—Kreidler was the German pocket-rocket and, to underline the point, became active in motor sport and Grand Prix racing, scoring eight world championship titles in the 50cc class.

UK specification Kreidler Sports 50s between 1974 and 1977 generally came with a four-speed gearbox, Bing 14 millimetre carburetter, 4BHP @ 7,500rpm, a well designed, soundly built, and high quality machine finished to a high standard—giving 48mph, fast and strong. Kreidler sales in the UK though were never particularly good because of the machine’s high price tag, and that mopeds generally failed to ingrain into British motor cycling culture in quite the same way as they did on the continent. The final straw came with moped re-definition in the UK, implemented from August 1977, limiting the maximum performance to 30mph. That effectively concluded all prospects of selling any more fast and expensive Kreidler mopeds in Britain.

European specification models with five-speed boxes, bigger carburettors and higher power offered even greater performance: 55mph! Kreidlers really are right among the top rated road-going sports 50s and, while the Italian 50s developed a reputation for going fast—then blowing up, the Kreidlers developed a reputation for going fast—and keeping going!

Our Kreidler Florett certainly looks a solidly built 50cc MoKick motor cycle, nice and smart, with a massively finned cylinder and head poking out from the ‘easy-clean’ engine cowlings. There’s not really much else to see on a Kreidler engine since everything else is panelled over, but it does look powerful and purposeful. The side panels proudly proclaim ‘RMC Elektronik’ on one side and ‘Grand Prix - Super’ on the other.

We check the weight, 13 stone 5 pounds or 85 kilogramme; that’s a lot of metal there, and it’ll probably want a powerful engine to move that around. Try it for size, a comfortable dual seat, firm suspension, all very solidly built; look at the instrument panel: a speedometer up to 120km/h and a tachometer up to 12,000rpm … we are now entering the jet age! Trouble is, it doesn’t actually go, and the workshops have to get it running first.

The main problem appears to be that, despite a full tank of petrol, there’s no fuel getting though the tap on either main or reserve. The workshops have a ‘quick fix’ for this sort of problem in the form of an air-line, an unsubtle blast up the pipe in both positions instantly returns the flow, but there’s a feeling that the carburetter condition should also be checked out … hold on? What’s going on here? That looks like the expected Bing carburettor, but it’s only got a tiny little hole up the middle! Blimey, yeah, it’s only 10 millimetre bore, and so is the inlet manifold! Even a Puch Maxi moped has a 14 millimetre Bing—this Kreidler looks like a restricted model. Right, no kidding!

Let’s have a look round the bike while the workshop deals with the carburetter… The chunky cast alloy wheels are very solid construction, with 2.75×17 tyres, so this is a machine that is going to be well planted on the road. Telescopic forks, swing-arm rear suspension, nice big drum brakes, there’s no questioning the obvious quality of the engineering. We fail to find any UK ‘rating plate’, which probably isn’t surprising since the bike is believed to be a Danish market import, which might tie up with the km/h speedometer.

There’s a small lockable toolbox neatly tucked into the back of the seat, and a plate under the saddle identifies the model as a K54/312, but we have no specs for these machines, so we’ll just have to press on without.

After cleaning out the carburetter, fuel runs through OK, so put on the choke, push the ignition key down to turn on, a couple of jabs on the kick-start and it soon fires up. The exhaust tone sounds nice and crisp, but we’re not now expecting anything spectacular with knowledge of its limited condition. The speedometer indicates nearly 36,000 kilometres, so surely it can’t be that restricted?

Throttle response seems rather ponderous, probably an effect of the carburettor size. Clutch action is good, down for first gear, initial pull away is confident enough, but the rising revs readily break into a bout of four-stroking at little more than jogging pace—this is not a good sign.

Into second, and the same four-stroking combustion breakdown soon occurs, so into third, but it’s becoming pretty obvious that acceleration, as such, is sadly lacking. Wind it open, crawl up the gear for a change into fourth … into fourth … where is fourth? The gear-change just seems to bottom out with nothing happening! We click back down the box, then up again, counting the gears: first, neutral, second, third … no, that’s definitely it, there’s nothing beyond third but the end of the gearbox. Not only is the engine severely restricted, but so is the selection of ratios! Presumably the stifled motor wouldn’t be able to pull anything more? We know the tuned Dutch Kreidlers will rev right off the tachometer, so what will the restricted motor actually rev to? Even full throttle in neutral will barely get this motor to 8,000rpm so you couldn’t rev it out whatever you tried!

A plastic moulded blanking plate on the steering headstock proudly proclaims ‘World Champion’—but this bike obviously isn’t! If the motor was tuned to go how a Kreidler normally should, then it wouldn’t be any use because there aren’t enough gears in the box. It’s a dead loss!

Mustering our pace bike to continue with the test: best indicated on flat 40km/h or 24mph on the pace bike. Downhill, full crouch, indicated less than 50km/h, and just 27mph on pace bike. Our following pace rider reported the exhaust tone as a complete mess of four-stroking rev break-up and bluster from limited porting, carburetion and restricted gas transfer. There’s nothing actually wrong with the way the motor runs, it simply complies with its market design specification and, basically, there’s no way this bike is ever going to go any faster in its standard state of tune. Our conclusion is that this Danish market 50cc MoKick is probably restricted to 40km/h, so there you are—nothing limits the performance of your bike like government legislation.

It’s a sad to see a quality-built sports Kreidler reduced to a whimpering, muzzled poodle by government regulation. Our K54 was a thoroughly miserable machine to ride, absolutely no enjoyment at all.

The Kreidler company went out of business in 1982, its trademark rights being sold to businessman Rudolf Scheidt, who contracted the Italian Garelli company to build mopeds with the Kreidler brand until 1988. The Kreidler brand rights were subsequently purchased by bicycle manufacturer Prophet, who continues factoring Asian-built scooters and light motor cycles to sell under the Kreidler logo—an unfortunate end for any classic marque!

Next—We last left this manufacturer around 1939, just about when they finished producing vélomotors due to unfolding European events at the end of that decade. Time ticks on, and twenty years later we pick up our thread as this French Lion has moved on, and is now making mopeds … and another 40 years after the moped? Then what?

This article appeared in the

April 2014 Iceni CAM Magazine.

[Text & photographs © 2014

M Daniels.]

A great double-take title for our second feature, Sheep in Wolf’s Clothing, but how apt!

Many sport Kreidlers have a powerful performance reputation for 50cc, but our Danish market feature machine was a real letdown. Even owner Harry Sylvester didn’t know the extent of its limitations since he’d never actually run the bike, though suspected it to be of quite a limited specification.

As if the restricted motor performance wasn’t bad enough, to discover it only had three gears was the final straw. The bike was terribly slow, seemingly restricted to 40km/h and a total misery to ride, but would probably keep running for ever since it would seem practically impossible ever to wear its motor out.

The Kreidler was collected from Harry at Leicester in August 2012, along with the Casalini David PT trade carrier moped featured in our previous edition. The two-times run to Leicester and back to collect and return the two bikes burnt around £50 in diesel fuel on each run. Taking two bikes at a time helps to spread the cost, though the Casalini was always the main focus and the Kreidler was only ever a sideshow extra to make the trip more worthwhile and economic.

Was the restricted Kreidler worth our trouble? No it wasn’t. What a disappointment!

The last time we rode another such handicapped ‘sports’ moped was the Spanish market specification Douglas Vespino Rally Tourist back in October 2008—that was another miserable machine too.

The extent of the performance and gearing restrictions would render any attempts to improve this Kriedler motor practically pointless, it’d just be easier (and probably cheaper) to replace the whole engine.

Somewhat aptly, the feature was sponsored by Les Gobbett of the Leicester Enthusiasts.