The Zündapp factory in 1957

We join our tale during the First World War. The year is 1917 and, backed by the giant weapons manufacturer Krupp and machine tool maker Thiel, a new company under the name of Zünder und Apparatebau Gmbh is founded by Fritz Neumeyer at Nuremberg for the purpose of producing detonators. This probably seemed a good business during wartime, but as the conflict soon ended and demand for munitions equipment dramatically declined, then the company would have to find something else to do.

Neumeyer became sole proprietor and launched his first Zündapp Z22 motor cycle model in 1921, under the title of a Motorrad für Jedermann—a ‘motorcycle for everyone’. This 211cc two-stroke was a simple and reliable design that sold widely and assured continuation of the concern. Zündapp began manufacture of heavy motor cycles with the K-series from 1933 and, from 1940, produced more than 18,000 KS750 motor cycle combination units with a locking differential and driven side wheel for the Wehrmacht in World War 2.

With the German economy impoverished following the war, Zündapp returned to building more basic models and scooters that were more suited to the time, building its last large 600cc motor cycle in 1951. From now on the business would concentrate on lightweights. The first Zündapp Combimot KM48 motorised cycle attachment appeared in 1953, as a 48cc, 1.2BHP engine, 38mm bore × 42mm stroke, with belt drive to the rear wheel. The same year also saw a new chain-driven series with 23-inch wheel models: 400 & 402 chain drive and 401 & 403 belt drive powered by the same basic engine, though these were sold as complete machines, and more commonly came to be known as mopeds.

German specifications of the time required these early mopeds to be built within a maximum weight of 33kg, so the light construction would present some engineering challenges and limitations to various manufacturers’ designs. 1954 introduced a developed 255 engine of 49cc; 39mm bore × 41.8mm stroke, and a new series of 26-inch wheel models: 408 & 409 chain drive and 410 & 411 belt drive.

Zündapp moped models are listed as first imported to Britain from December 1954, and our first featured machine genuinely appears to be an early UK market 408 example. The registration serial dates from 1955, the rear mudguard is pinned with an old dealer badge ‘Great Western Motors of Reading’, which ties up with the index letters, and it was previously fitted with an mph speedometer (though currently replaced by a km/h instrument following the failure of the original equipment).

The engine is single-speed with a multi-plate dry clutch worked by a grip-lock lever to enable an effective neutral. The KM50 motor is rated at 1.5BHP @ 4,500rpm and is fed by 10mm Bing carburettor. The exhaust is a chrome expansion barrel under the motor, finishing in tailpipes to each side. The rims are particularly nice quality, being lightweight Magmeg alloys, and are shod with 26×2 tyres to a rigid frame and pivot-sprung front forks, which often provide some unusual technical fascination to people trying to figure out how they work.

The spine frame comprises a single formed tube with petrol tank below the saddle and is sparsely appointed to comply with the German market design weight requirements. Out of curiosity, we roll our machine onto the scales, and 36kg, so considering the bike is fully fuelled and oiled, there’s a rear carrier and prop-stand fitted, and half a ton of glass fibre bonded to the rotted remains of the original steel side panels to hold them together, yes ... the weight limit would seem possible. Because of the standard 26-inch cycle size wheels, the frame appears long and slender, looking gently styled and visually well balanced with its Deco pattern side panels and striking gold paint. It’s certainly an attractive and interesting machine to view—pleasant and graceful to the eye. Controls are simple: a twistgrip throttle and front brake lever that feels very spongy when we easily pull it almost back to the grip, so there’s an expectation that that half-width front hub isn’t going to be offering much braking performance.

There’s a simple lighting off–on switch atop the headlamp shell, clutch grip-lock lever on the left handlebar, then nothing else, except what looks like a small trigger decompresser or choke lever mounted off the clutch lever bracket? Well there’s certainly no decompresser on the cylinder head, and the Bing choke is the usual little push-down pin on the top of the carburetter, so it’s neither of those things ... so, follow its cable into the steering head casing? No, it’s really not obvious what it does, so thumb the trigger ... and a cycle bell rings from within the headstock! So there’s a novelty for you, though not strictly compliant with regulations in this country. Fuel off–on–reserve turns on at the bottom right of the tank, tilt the bike upright and the alloy tube prop-stand springs up on its own. Though the Wittkopp leather saddle is set as low as it will go, the tall frame makes the seat a fairly high perch, then pedal away and drop the clutch. The motor burbles into life almost immediately, so a really easy starter, then trickle along for a few moments on choke before teasing round the twist-grip to test if the motor will take throttle ... yes it does so, tracked by our pace bike, we ease up the lane to get a feel of how our ship sails.

It’s immediately obvious that the performance isn’t going to be setting the road alight today and initially settling down to an indicated 30km/h gentle cruising speed, our escort is already looking a little bored as we check off this first pace at 19mph, so our speedometer seems reasonably representative. Low speed torque proves quite good, so it’s easy enough to pull away from a standstill without any need to pedal assist. Nor does it require excessive revving or slipping in the clutch, so seemingly quite capable at first impression. Four-stroke phasing begins to creep in as the dial goes past 30km/h, so we’ll run the bike along for a few miles to see if this abates as some heat works into the engine.

The general ride seems fairly comfortable and stable enough for us to be unconcerned about the steady pace; our ancient Combinette proves a pleasant mount and is content enough to run along at a brisk cycling pace ... while watching the forks quivering back and forth as they act on the springs. Easing the bike a little faster as the engine gets hotter, we find we can coax the needle up toward the 40km/h marker (25mph), though this speed generally proves difficult to achieve in an upright position without the assistance of a tailwind or favourable light gradient fall. Turning into a good tailwind and tucked into a crouch, our best on flat wavered past the 40km/h marker and was clocked by our pacer at 28mph. Our downhill run briefly saw the needle bouncing vaguely somewhere around the 50km/h+ indication, at which speed the motor was clearly most unhappy, growling angrily, and with lots of vibration. The pace bike reported our peak dive as just touching 33mph, before charging into the climb section with the throttle wide open and all guns blazing.

The earlier torquey impressions gave a suggestion the KM50 was likely to make a reasonable account on the ascent, and it proved quite capable for such an elderly veteran, cresting the rise around an indicated 28–29km/h, which the pace bike returned as 17mph. No pedal assistance required, and not the slightest suggestion that the hill was of any concern.

Now on the return leg and with a thoroughly hot engine, we were pushing the Combi along at a harder pace, and the handling and road-holding proved quite reasonable (within the limitations of the performance). We were now building enough confidence to charge a few corners, but running past the 35km/h line brought back some intrusive vibrations, so it wouldn’t be a pace to maintain for long.

The 408 to 411 models with 1.5BHP KM50 motor were rated around 45km/h (28mph) performance, but we found this quite difficult to achieve under general on-flat riding, the pace bike reporting our machine would rarely exceed 25mph, except under favourable conditions. Whether these vibrations could be attributed to the two-point engine mounting, a slightly tight drive chain, or possibly tired main bearings, we couldn’t really quite say, but some of these factors could probably be improved a little. (Subsequent investigations within the motor did find the inner output shaft bearing to be significantly deteriorated, and its replacement quite transformed smooth running.)

We haven’t mentioned the ‘coaster’ back-pedal cone brake, because it was utterly useless, like these things always are on mopeds. You could lift your whole body off the seat and stand on the back pedal, to practically no effect at all. The only time you could get any rear braking effect, was when wheeling the bike backwards and it might suddenly decide to lock the wheel ... wretched thing!

In the Zündapp factory: setting engine timing

We tried the lights, and they’re comparable with bicycle lamps—just enough to be seen by other motorists, if you’re lucky!

Returning from our run, the engine ticked over steadily, but there’s no obvious way to stop the motor ... so though it might seem an unlikely way for any manufacturer to recommend stopping a machine, we ended up having to stall in gear. With these old model mopeds it was often general practice to set the carburettor adjustment for the motor to fade out on closed throttle.

The old fashioned 408 to 411 models were only listed for 1954–55, when the big 26-inch wheels gave way to the smaller 19/23-inch conventionally adopted moped sizes, and increasingly ‘filled’ frame designs with leading-link forks.

At the same time that Zündapp was producing our previous ‘big-wheel’ Combi, they also presented a completely different range of 404 & 406 pivot-sprung fork models from 1954, and 405 leading-link fork moped models for 1955 based on a two-speed variant of the same KM50 motor. In this case the motor was up-rated to 1.8BHP @ 5,000rpm by the fitment of a larger Bing 12mm carburettor—and by rather good fortune we’ve been lucky enough to happen across one of these 405 models of the same 1955 vintage as our base machine.

This bike also seems to be an official UK market machine, but we’re confused by the registration serial indicating Cardiff 1963, so either they weren’t selling so well, or maybe Zündapp were ‘dumping’ a few old model leftovers on foreign markets—which wasn’t an uncommon ploy. Reference back to the owner about originality of the registration, returned that the bike had previously been subject to some registration transfers, so the number was unlikely to be relevant. It’s a little annoying when a bike’s history becomes lost in this way, but that’s the nature of the game.

The spine frame of our two-speed Combi model appears similar to the base machine, but any similarity pretty much ends there. The 405 forks have leading-link suspension with nice cast alloy link arms. There’s a large, chrome-sided fuel tank mounted atop the frame behind the headset and a toolbox now fills the frame space below the seat. Tyres are 23×2 on 19-inch Magmag alloy rims, with nicely cast and finned full width alloy hubs. Both mudguards are generously valanced with side shields, there’s a centre stand instead of the prop, and a full-length chrome exhaust system.

Once again rolling our machine onto the scales, this moped reads 10kg heavier than our first—46kg! There’s no way this machine was designed and built to any 33kg weight limit.

The cycle imbues a particularly quality presentation due to the number of alloy components, but extensive application of these lightweight materials was probably originally intended more to keep the weight compliant with regulations than presentation of an exotic finish. We note the fuel tap off–on–reserve is on the left with this model, to match the carburettor being mounted on this other side too, so the two-speed is using a different manifold arrangement. Choke pin pushes down on the 12mm Bing in much the same manner, to lift off automatically when the throttle is opened, but we also warily note an adjustable main jet sticking out through a port in the side panel (more about that later).

From just the same simple off–on lighting switch on top of the headlamp, handlebar fittings are still very minimal, just throttle twistgrip and front brake lever to right hand, and clutch twist shift to the left. The little trigger lever cable-operates a decompresser valve in the cylinder head on this model, which we expect will normally be required to enable starting with the two-speed gear arrangement (but have no idea of the puzzlement that lies ahead at this stage). The frame-front bell is replaced by a chrome blanking cover on this model, and a squeezy bulb hooter replaces the bell.

Expecting a conventional starting method of spinning over the pedals in neutral to fire up the motor, we’re somewhat taken aback to find this doesn’t work at all, and the bike simply cycles along the road instead. OK, maybe it’s like the Mercury Mercette or Hercules Her-Cu-Motor and you’re meant to start it in gear, and yes, you might do this—except the dysfunctional decompresser doesn’t actually vent through the valve, so it’s not so easy to get the motor spinning.

After a little trial and investigation with our pace rider, we conclude the intended starting procedure is to engage second gear while still holding in the clutch lever, then you can kick over the motor with the pedals with the drive disconnected. Once started, engage neutral or select first to pull away. The clutch seems to operate after the gearbox, which is a little back-to-front, though we have come across this system occasionally, and it does take a little ‘adaptation’ in riding technique.

The gear-change/starting system is neither a natural or friendly system to use and many riders will probably find it particularly irritating. Many complaining customers found it very annoying at the time, and Zündapp soon progressed to a more conventional motor design.

Having finally figured out the initial quirks and got our motor started, it runs smoothly enough and seems quite crisp on throttle response. Though the clutch/twistgrip takes the usual wrestling around to its gear engagement positions, actual selection proves clean and quiet in operation, so gives maybe a better impression than a clonky Puch or NSU. The motor revs eagerly and clutch feeds in well, so acceleration is smooth and brisk, then a change to second finds the ratios reasonably spaced. This Combinette makes a smart and easy getaway, so initial impressions are that it may be a good and quick little bike.

The gears seem well chosen for the general performance of the motor, though we have been informed by the owner that sprockets have been changed to gear the bike up somewhat and presume the 404–405–406 range was originally sold in a lower ratio configuration. Zündapp rated this model at 50km/h (31mph), so we’re expecting our test machine may possibly prove a little faster. Exchanges with our pace bike established that our 45mph VDO speedometer was reasonably representative, as we cruised easily along in the upper 20s to work the motor temperature up. It wasn’t far down the road before our pace rider pulled alongside to complain about the wailing induction roar and cracking exhaust tone as the motor ran through bouts of four-stroking. The noise mightn’t seem particularly intrusive to the rider, but was certainly enough to quickly irritate our pacer following on the rear quarter.

The good and easy acceleration in gears and smooth running up the range, naturally leads the rider to run this bike along at a quicker pace than our earlier model and, with confident handling and better braking functions, this Combinette will easily out ride the single-speed base model. Our best on flat reading paced at 30mph, though upper rev running felt to be holding back periodically with flat spots and four-stroke phasing, so we pulled up to tweak the adjustable main jet to a weaker setting. This could tune down the four-stroke phasing at top end running and smooth the exhaust tone, but could easily be trimmed too far back to find top end running had now flattened off—then trim too far forward again and you’re back to square one. You can just spend forever fiddling with these wretched jets, and rarely get them right, then if you stop the machine or the temperature changes—you seem to have to start twiddling all over again! These adjustable jets seem less of a tuning boon, and just more of a constant irritation. Our conclusion was that the bike would probably go consistently better with a conventional jet arrangement, so just set the carburetter properly with the correct main jet and chuck the damn thing away!

Downhill run just clipped 35mph according to our pace bike, though the VDO speedometer on our mount only indicated 31–32, so seemed to show slower towards higher speed. The following uphill climb was easily managed in second (top) ratio, dropping back to 25mph to crest the rise easily with no doubt whatsoever that the motor was well up to this easy task. The wholly different characteristics of this two-gear machine easily maintained a higher average pace than the basic model and rarely dropped below 25mph around the course—an interesting contrast to our other machine, which barely managed to reach 25 except under the most favourable conditions.

Once again, this bike ticks over when we return, and this ‘stall-in-gear-to-stop’ thing is beginning to bug us now, so it comes down to the last resort—we’re going to have to read the manual. A quick browse through the booklet finds a page ‘Control Devices’, number 3—light and cut out switch. Back to the bike and, yes, turning to the left puts the lights on, and turning to the right kills the engine ... easy when you know how.

Apart from the difficult starting requirements, the back pedal brake arrangement was particularly irritating on this machine, completely locking the back wheel solid and jamming the pedals if you so much as barely thought of backing the bike—even in neutral! This repeatedly caught everyone out and was a constant frustration to handling the machine that raised more than the occasional abusive remark. The only way to beat the problem was to pull in the clutch every time you wanted to move backward—but it’s not a natural thing to remember and it is going to drive you quite mad if you own one of these models.

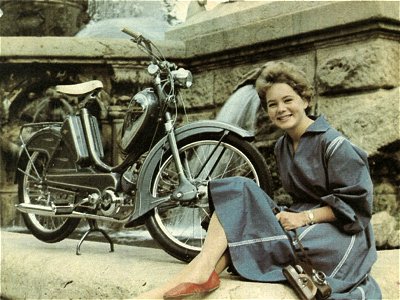

Zündapp certainly received the feedback from its customers to develop and begin introducing more rider-friendly designs in 1956. Zündapp continued developing its moped and mo-kick models, popularly and successfully selling machines into the early 1980s.

Sales into the UK market were distributed by Ambassador, but became somewhat disrupted when Kaye Don retired and sold the business on to DMW. There were a number of unique and special ‘export’ models particularly sold onto the British market, which are very rare across the European continent. The early 1960s’ 70cc Falconette, KS70 and KS75 models are quite unusual and could be most desirable to Zündapp collectors abroad. Faced with a general decline of the motor cycle market and falling sales in the early 1980s, the German Zündapp company fell into bankruptcy and closed in 1984.

The entire production line and intellectual property rights were bought by Xunda Motor Company of Tianjin in China, where production resumed in 1987 until the early 1990s. Oriental manufactured parts are still widely available to maintain many Zündapp machines in use today.

A Zündapp company is still in business, making Honda based four-stroke motor cycles and electric bicycles.

Next—Back to France in time for our summer issue. A lazy afternoon in the sunshine at the bistro, sitting out in the garden, grazing over lunch with a glass of cool wine, just the sound of birdsong … and mopeds buzzing in the distance. Our main feature tests three comparative Mobylette models, and what you get is all in the number—Best of Three.

This article appeared in the

April 2014 Iceni CAM Magazine.

[Text & photographs © 2014

M Daniels.]

The title of our Detonators lead feature related back to Zündapp’s origins, and we’d known of our two Zündapp 408 and 405 models for over a year before the seed of a plan began to germinate with the obvious idea to put the two together for an article. A fine plan, but the bikes were some 60 and 80 miles away in different directions, and to co-ordinate the joint main cover shoot that we desperately wanted would require some special arrangement to get the two bikes together.

The Zündapp feature was created very quickly over just one week towards the end of April 2013, initiated by the gold 408 model coming into the workshops for clutch service. Well, less of a service actually, more a re-assembly, since it actually arrived as a semi-basket-case with the engine out and in pieces, carburetter, electrics and panels all off. Everything was sorted within two days; then the deal left the bike at our disposal until collection by its owner, Bob Castle at Hatfield.

We went to collect the green 405 model from Paul Efreme at Billericay just two days later, and with our pace rider booked for that afternoon, the van arrived and we practically unloaded the bike straight out for the road test.

Both machines were tested in the same afternoon, and both machines were photo shot the following day. The cover sequence came together on a calm, pleasant and sunny afternoon, in tranquil surroundings at the local chapel, the peace of the afternoon only occasionally broken by the piercing cry of pheasants across the churchyard. Both bikes proved very photogenic and, in such a setting, there were plenty of great pictures to make the final editing selection a difficult choice.

Despite the two motors being derivatives of the same basic engine with only a 2mm increase in the carburetter venturi, the two-speed 405 showed a dramatic improvement in ride-ability and performance, though when it came down to choice, we somewhat preferred the stately elegance of the gold 408. Zündapp’s build quality seemed good and consistent throughout, everything exactly and nicely finished outside and in. Even 60 years on, both Zündapp models still proved capable and effective machines to use.

Drafting of the text was largely completed in two marathon overnight writing sessions, then the whole package stowed into its digital time capsule for some distant day when it might be worked toward completion for publication.

Both bikes were collected by Bob the following week, and Paul’s bike returned en route, so our whole production cost involved just one there-and-back trip to Billericay, diesel fuel around £15. Bob Castle also sponsored the article.