Sponsored by Denis Bishop,

IceniCAM reader and AV78 owner,

County Down, Northern Ireland.

Our continental language lessons continue with a little French mathematics, and the solution to last issue’s technical puzzle, ‘The answer is 234—now what adds up to the question?’

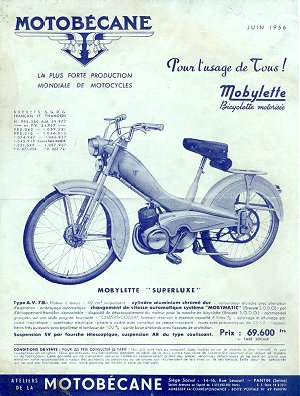

Early Mobylette mopeds were originally based on traditional tubular cycle frame brazed lug construction, which was succeeded by the first pressed-steel, welded chassis assemblies for the AV76 from 1957.

By mid-1958 the new ‘Dimoby’ double clutch completely replaced the earlier so-called ‘automatic’ clutch that actually required the rider to ‘pedal-off’ to engage the drive. Now the operation was genuinely automatic.

AV77 & 78 models also introduced a variator system, where the motor swings against a spring as the engine revs increase, pushed back by a centrifugally driven pulley, and raising the driving ratio by 39%. There was a lot of rider appeal in such a simple-to-operate, fully automatic, and effectively geared clutch and drive system—unfortunately it proved pretty disappointing to ride mopeds with these early arrangements.

Letting this physical package down was that all these recent developments were still centred upon the basic AV7 motor. With small transfer and exhaust ports, lowly 6.5:1 compression ratio, tiny 10mm Gurtner carburettor, and rated at just 1.4bhp it simply didn’t have the strength to make anything of the new drive gear.

Riding a standard AV78 can certainly provide an appreciation of these limitations. The first variator systems were six-ball operated, pretty much kicked up into high ratio almost as soon as you took off, gradually laboured up to pace, and failed to effect any ratio change when you encountered an incline. The only way you could get them to change back down at all, was to actually stop! The feeble motor really struggled to build up any speed against headwinds or any incline, and generally offered little practical performance improvement over its un-variated siblings. It could often prove that the rider of a fixed drive Mobylette model could make better headway against adverse conditions, simply because the lower ratio might allow the rider to enable better revs. The only small benefit of the vario-motor constantly labouring against the high drive ratio was that it was much less afflicted with the irritating bouts of 4-stroking that plagued the fixed-drive models toward higher revs.

Motobécane attempted to address the ineffective variator by reducing the cast aluminium centrifugal cone to a 5-ball set on the later AV78s, but it made no difference, the variator still wasn’t variating, and the AV7 motor still wasn’t up to the job.

To give some impression of how bad the Mobymatic speed-change variator was, you have to appreciate that by the time Motobécane finally got it working properly and effectively in the late ’60s, the centrifugal cone was reduced to just 3-balls in a plastic moulded cage.

While the introduction may appear somewhat critical, what needs to be appreciated is that we’re not just looking at any old Mobylette. At the time the AV78 was being built, they represented the very top model in the manufacturer’s range.

These, now rusty, old veterans were actually Motobécane’s cutting-edge flagships of their day.

The first of our trio of old battleships is Mobylette AV78, Frame number 2187666, Engine number 2004669 registered 31st October 1958, and issued serial 187 ENK by Hertfordshire authority.

It seems that many people very much appreciate machines preserved in their original condition, rather than pretty and shiny examples that have had their soul restored out. Anyone looking for a bike with character can certainly find it here—by the rusty bucketful! Where do you start? It’s like opening an ancient tomb and finding this bike mummified inside!

Right on the leading tip of the front mudguard, and undisturbed for 52 years, is riveted an old pressed brass dealer plate, reading ‘George Wilks, Radlett. Tel. 5772’, now that’s a nice touch! From thereon back, there’s no questioning that this bike retains its original Bleu Clair (light blue) finish—that’s if you can find traces of it beneath the practically all-covering surface rust! Though many observers might perceive this machine being in danger of crumbling into a pile of dust at the mere prod of a finger, not so—the oxide patina is purely surface, and the actual metalwork remains remarkably solid, which is probably some tribute to the quality of the materials.

Much of the styling is easy on the eye, in an old-fashioned, arty kind of way, quaint sweeping curves that all flow together, very much a product from a bygone age. The teardrop shaped toolbox below the saddle is a classic example. It doesn’t need to be like that, round would do—but wouldn’t look so elegant. Then the toolbox ends, round formed in pressed alloy, and emblazoned with the ‘M’ symbol, they don’t have to be like that, but they are. So deco period, so old French! Despite its aged corrosion, the artistic style still shines through.

Starting old Mobys is pretty straightforward. Thinking of its tired old legs, we nudge the bike off the stand, push down the petrol tap for on, twist the throttle forward for decompress, pedal down the road, the engine spins and twist back the throttle with a flick on the choke trigger ... and the engine gently putters into life.

Except for conversion to three-ball clutch for better operation, the original variator engine has been refurbished to standard specification, so we have a rare opportunity to experience the performance of one example pretty much as-built. Still equipped with the original internal HT-coil Novi magneto-set, the motor has the small-ported, continuous-fin cylinder barrel, with 6½:1 compression head, and BA10mm Gurtner carb, so still barely nudging out its factory rating of just 1.4bhp.

Opening the throttle from standstill raises the revs to a gentle Hooverish hum, as low gearing from the variator aids take-off without much real need to pedal assist, though a little kick on the pedals might feel to be rather kinder to the automatic clutch. The engine swings back as the variator changes up through its range, pulling gently but steadily with some impression that the bike could build up to a reasonable performance—but as the ratio increases, optimism is replaced by an appreciation that our standard mount is hopelessly underpowered. The variator changes up to a gear that the motor can barely pull, and with a flat exhaust tone, just constantly labours against this overdrive.

It quickly establishes as the norm to ride with the throttle wide open practically all the time, in a constant effort to maintain any reasonable pace against the prevailing conditions. Fading against marginal inclines and subject to wind direction, the rider may sometimes feel a little redundant, barely influencing the way the bike might respond (or not) to throttle against natural geography and whims of the wind.

The quaint Veglia milometer with its numbers presented in individual windows, remained frozen in time at 4,039 miles, as the white dial of the speedo failed to indicate any motion at all. The pace bike however was tracking our run, to a best of 25 on the flat, then peaking at 34 on the downhill section, though inevitably fading on the climb up the other side as the incline took its toll against the low compression ratio. Our speed from the bottom of the dip falls away ... slower and slower ... will we make it up hill without resorting to pedal assistance? Keeping the throttle on load, the variator fails to change down despite its three-ball conversion, but feel the euphoria of achievement as we do succeed in crawling to the summit at 15mph on engine power alone.

The elegant aluminium rear plunger suspension units work every bit as well as they look, smoothing out the ride, yet keeping the tail-end on track through the bends without any weave or wallow that can afflict many lightly engineered swing-arm mopeds of the following decades. The telescopic forks also effectively soaked up the surface from the front, so, completely unchallenged by the feeble output from the motor, the bike handled and rode really well.

Still retaining its original saddle, the seat proved rather saggy and unsupporting. Looking under the cover reveals not springs, but rubber bands, a bit like miniature bungee cords for strapping items to your carrier. In 50+ years, their elastic properties appear to have rather perished.

Both brakes prove very good, and far outperform the engine. The well-engineered Prior full-width hubs would still prove quite capable for a machine producing twice the power—and in just two years time they would be doing exactly that on the new AV89, but such moped performance was just a distant dream back in 1958.

The light switch clicks round to ‘On’, but nothing happens. The rear lamp seems to have no bulb, and presumably the resultant rush of power might have accounted for the headlamp bulb, but the horn also fails to respond to its button, so we decide to look no further.

One year on, and number two in the line of battle comes Mobylette AV78, Frame no. 2194892 registered July 1959, and issued serial OCT 893 by Lincolnshire authority.

Again, this bike is very largely in original condition, but differs rather from the first machine in that it’s finished in paint rather than corrosion. Though ostensibly identical to the ’58 machine, one obvious change has occurred to the toolbox beneath the seat, which has reverted to a plain cylinder with steel ends. This second machine also demonstrates the original internal HT-coil Novi mag-set, and has also experienced a three-ball clutch conversion for better variator operation.

The motor, however, despite its same physical appearance, has received some tuning modifications to improve the performance. While the cylinder head wears exactly the same finning pattern as the original 6.5:1 item, the little serial disc riveted to its right side fin tells us this head has come from an AV89. Inside this the combustion chamber looks quite different. Instead of the concavity of a plain hemisphere with 7½cc, the AV89 head has two side-squish bands that close its internal capacity to 5½cc, and raises the compression ratio to 9:1.

Looking along the head joint, we can also see that there’s no gasket fitted, the joint being sealed with silicone instead. The effect of removing the 0.63mm aluminium head gasket for a 9:1 head bumps it up another point, so this engine is running at 10:1, which should give a better edge to acceleration, hill climbing abilities, and pulling against a head wind.

The original small-ported, continuous-fin cylinder barrel is still fitted, but the exhaust port size has been extended from 20 × 7mm to 20 × 10mm, so the spent gas clears better at speed, and running doesn’t become afflicted by the bouts of four-stroking that invariably affect small transfer cylinders at revs.

The original Gurtner BA10mm carb still graces the inlet manifold, so that seems to pretty much cover the extent of the modifications. Without actually running the bike on a dyno, from 1.4bhp, the motor output has probably increased up to around 2bhp.

Response to the throttle is immediately obvious, this bike is rather more enthusiastic in pulling away from a standstill, and climbs up to speed much more willingly.

This same quaint Veglia instrument also proved unwilling to share its indications, apparently suffering the not unusual problem of a broken drive cable. The bike’s performance, however, would not remain any secret, as the pace bike was there again, tracking our run to a best of 28 on the flat in still air, and even gracing 30 with the aid of a light tailwind.

The downhill run clocked 37mph, and charging the incline in the same manner as its older brother, this younger sibling gave a better account on the incline, only dropping to 19mph as it crested the rise.

The engine modifications really do appear to deliver performance improvements in all areas, and certainly make the bike feel less susceptible to the elements and geography.

The same original saddle on this bike proved more supporting as the miniature bungee cords appeared in better condition, though still failed to deliver any real appreciation of improved comfort.

Both brakes proved very good, and still easily outperformed the uprated engine.

The lights switch clicks round to on, and yes, the lights work—the headlamp glows away like a dull yellow moon, and doesn’t look as if it’ll be generating many light pollution complaints from the local astronomical society.

The electric horn makes only a feeble croaking noise when provoked by the push of its button, so probably explains why a bulb hooter complements it on the handlebar.

Another year on and number three in our fleet sails into view with Frame number 230982, Engine number 233623, registered on 20th February 1960 and issued serial KPV 684 by Ipswich authority. The bike was supplied by the local Mobylette main dealer Jacobi’s of Norwich Road, Ipswich, and over half a century later it’s still in the town, only a few miles from where it originally came. Jacobi’s agency is sadly long gone, but the bike remains, and it probably doesn’t take a lot of working out why this local legend has famously long been known as "Old Rusty".

We feel it may be reasonable to describe this machine as ‘preserved in original condition’, since its corrosive decay has been suspended by liberal doses of penetrating lubricant and wax/oil treatment that has effectively halted any further decomposition. Maybe the oxide and greasy finish isn’t quite everyone’s interpretation of ‘preservation’, but when Old Rusty attends any local events it invariably encourages more admiration and wonderment than any pretty and shiny restored machines. 53 years of history and character have grown into the way the bike looks today, and we can only hope that it stays that way.

Original accessory carrier frames adorn both sides of the back rack, and they’re not just for show since the bike also has some tasteful period Midland tartan panniers which can be readily clipped-on for functional service. The saddle is also tastefully clothed in a matching Midland tartan saddle cover—yes, even Old Rusty might have been considered a fashion icon ... back in the early 1960s! The under seat webbing still comprises miniature bungee cords instead of springs, still feels rather saggy, and not particularly comfortable to ride.

The under saddle toolbox is the same round pattern as our second 1959 model, but the 1960 model sports another notable dating feature—Old Rusty mounts a white external HT coil beneath the petrol tank, bolted through a mounting boss that had been added to the frame half pressings. Many riders of old internal-HT coil Mobylette models will very probably be quite familiar with the associated difficulties of the much-cursed early ignition systems cutting out when they get hot, then steadfastly refusing to restart until have cooled right down.

The Motobécane factory switched over to the external HT coil arrangement to address this perennial problem, and it was certainly a considerable improvement, though sometimes not a total fix as poor performance of the Novi ignition capacitor could also simulate exactly the same effect. Retro-fitment of an external HT system to early internal HT models is probably the best recommended method to attend the traditional ignition maladies, but the earlier frames were not equipped with an HT mounting bracket, so how and where to site the external coil can present some difficulties.

Old Rusty may look rather as if it’s never had any attention for donkey’s years, but that’s all part of the clever disguise—it’s a Q-bike (called after the principle of World War 2 Q-ships that appeared like humble merchant vessels to lure unsuspecting enemy submarines and surface raiders within range, then dropped their disguise to reveal they were bristling with weaponry). Rusty has received a similar motor uprate to our second test machine, 20 × 11mm exhaust port modification, an AV89 cylinder head, again running without gasket for 10:1 ratio, but this time the original AV78 badge plate has been returned to the right-side head fin complete with the original rusty rivets, so it looks completely authentic, even under close scrutiny. Once again the more reactive three-ball variator replaces the original 1960 five-ball set.

Carburetion remains the original fitment remote float AR10-501E carburettor, but modern fuel mixing has progressed beyond the days of smoky old mineral oil 20:1 mix—Rusty now clean-burns on 33:1 semi-synthetic. You wouldn’t really imagine that anything might have been done to the cycle chassis, but the original spokes were corroded down to little more than rusty needles, so have been re-laced with new galvanized spokes without disturbing the original weathered aspect of the hubs or rims. A little white oxidation of the plating and settling of surface grime soon cover any tale of the work, so no one would manage to spot the wheel rebuilds—you really wouldn’t know, but they’re a lot sturdier and safer now.

The rims are both shod with the now obsolete Cheng–Shin 2.00×19 rubber boots and new tubes. The Cheng–Shin was a hard compound and hard wearing moped tyre of firm construction, and quite suited to hard inflation for fast running.

Rusty’s motor is well bedded-in and nicely free-spinning from regular use under constant full-throttle running, which certainly doesn’t represent any stress for these models since the final drive ratio is so high—you’ll rarely encounter conditions to make the motor rev out.

The same Deco dial 40mph Veglia speedometer looks like another set that isn’t going to be reporting any readings, since there’s clearly no cable connecting it to the Graisser drive down at the front axle, so once again we’ll be relying on our pace bike.

Petrol tap down for on, and the lower petroil mix means Rusty runs strong and rich, and rarely requires choke. Just walk along beside the bike with decompresser engaged until the engine spins, turn back the throttle and the motor fires up with a clear and crisp popping note from the tailpipe that strongly suggests a bit of ‘baffle clearing’ has also taken place—then hop on and away! Rusty’s acceleration is surprisingly nippy and quite unexpected for the way the bike looks. The plunger rear suspension arrangement results in particularly good handling on corners and you can soon adopt a fast riding technique to maintain a pressing pace, which really wouldn’t work quite so easily on the later swing-arm models, which comparatively wallow through bends and feel nowhere so confident. Plunger systems can provide an effective suspension without the flexi-feel of the swing-arm on bumpy cornering, so the riding method is to charge into a corner, brake down to the speed you want to take the bend, wind open the throttle on full as you enter the turn, pick and follow a clean line through as you lean into the turn, and power through manoeuvre. There’re no wobbly surprises from the rear plunger set, and you soon develop a confidence for maintaining a consistent pace that many contemporary mopeds may struggle to match. Only Rusty’s uprated motor makes this possible. You couldn’t match the ride with any standard example, but the combination of better engine power and technique do go to make the old rust bucket a brisk little riding machine through twisty sections.

Braking performance from the nice quality Prior full width hubs proved well up to the demands of hard riding.

Our outward course found us pulling into a strong headwind, but still generally maintaining up to 29mph despite the adverse conditions. Having to work hard against the wind got the motor nicely hot for our turn into a crosswind for the second leg where Rusty worked up to 33, then return leg with a tailwind and crouched position 36mph best on flat. The tailwind flat section at full speed ran us straight into the downhill run, where the pace bike clocked our fast run through the dip at 46mph—a most commendable result, and Rusty handled it smoothly and easily! The following uphill dropped to 20mph before cresting the rise at 26, but the climb was handled confidently with never any thought that pedal assistance may become required.

Turn the dainty switch through 90° on the Luxor headlamp, and yes, we do have lights, and surprisingly they’re not too bad either! The Miller red lens glows like an angry ember from the searing power of the 6 Volt, 1 Amp (6 Watt) MES bulb. Headlamp bulb is 6 Volt, 15 Watt but actually reflects more white light from the aluminised reflector than the usual yellow, so the consumption must be fairly well balanced to the generator output on this occasion. One might even stand some chance of seeing where you were going at night, provided you didn’t try going too fast!

A stab at the decrepit looking horn button on the left bar surprisingly produces an intermittent and rasping ‘raspberry blower’ note, which somehow sounds very apt for the machine.

The AV78’s brief reign as top model came to an end in October 1960 as Motobécane delivered their new ‘Bronze Age’ at the Paris Salon in October 1960—the fantastic new ‘Grand Tourisme’ AV89!

This machine was a whole fresh package, new engine, band suspended leading-link forks with swing arm rear suspension pressed-steel frame, dual seat, and finished in awesome ‘Chaudron’ metallic bronze paint that glistened in the lights as if cast by the Gods from a boiling cauldron of gold!

The light Bleu Clair finish of the AV78 looked positively drab by comparison, and the writing was on the wall.

Accompanied by the launch of this new flagship, the tele-forked Spéciale 50 model sport version was an artistic styling stunner—so now Mobylette was really ready to bring on the ’60s! After the gutless old AV7 engine, it might have seemed pretty brave for these machines to be equipped with a dual seat and footrests, fully intended for carrying two people, but the AV89 motor would prove everything it needed to be.

Restricted porting within the AV7 cylinder was 20×7mm exhaust, with 18×6mm transfers.

Developed porting of the AV89 cylinder was 20×11mm exhaust, with 18×8mm transfers.

From 6.5:1 compression, the AV89 head bumped this up to 9:1, and an H14mm Gurtner now replaced the BA10mm carb.

Up from just 1.4bhp at 4,500rpm, the dyno read out 2.66bhp, so enough power to overcome the performance issues, and a plastic centrifugal cone, four-ball variator now allowed this system to operate appreciably better (though often still required a jolt from snapping on the back brake to induce the gearing to change down in preparation for a hill climb).

The old AV7 motor would probably barely rev much beyond its 4,500 rating, before restrictive gas transfer limited its rev ceiling. With the AV89 motor, the bigger ports let this engine rev beyond and away into the clear blue. It wasn’t just about more power to forge against headwinds, up an incline, or pull with a pillion passenger aboard, but the ability to rev so freely also offered the potential of being able to build up to a good speed under favourable conditions.

AV89 Luxamatic imports into the UK are listed from December 1960, joined by the Raleigh branded RM5 Supermatic version from February 1961, Norman Lido Mark 3 and Phillips Gadabout Mark 4 variants from September 1961.

Introduction of the AV89 series killed the old AV78 stone dead in its tracks. The model was discontinued immediately.

The AV78 had its good points, it was nice quality and rode well, but too old fashioned for the expectations of the new 1960s decade, and terribly handicapped by inadequate power output.

Next—From a relatively ‘modern’ AV78 French moped (only just over half a century old—a mere babe!), our coming feature brings us back across the Channel for a special encounter with a rare and unusual pre-war English autocycle.

Now if anyone might be thinking "Another generic Villiers-engined bicycle that looks much the same as every other first generation autocycle", suffice to say that not all pre-war autocycles had Villiers engines. There were some exceptions, though admittedly these were only built in quite small numbers and, over 70 years on, really are quite rare indeed ... surely IceniCAM hasn’t managed to bag something so exceptional for road test?

Look back at our track record for securing remarkably rare bikes, and you just know that we’re going to pull this off OK, but this is a very extraordinary autocycle that really ran Against the Grain.

This article appeared in the

January 2013 Iceni CAM Magazine.

[Text and photos © 2012, 2013

M Daniels.]

AV78 × 3 = 234. Seemingly an odd mathematical title for the second feature of our French sequence, but it does add up, so that’s OK!

The first and oldest AV78 was a machine ‘bought in’ by the workshops to start the article. This was actually a ‘second time around’ machine for the workshops, having previously been through before as part of a job lot of bikes. On the first occasion the input only comprised a registration recovery before being cheaply sold on as an original/unrestored project with documents.

The engine subsequently returned to the workshops for overhaul, but the owner’s project went no further and the bike remained dismantled for several years, before the workshops bought it back in again as a basket case. Since the engine was now a known quantity (as the workshops had earlier rebuilt it), it was just a matter of reassembling the machine, getting it operational and roadworthy—from zero to running order in just three days!

Completing this road test and photoshoot to initiate the AV78 article in February 2010, the bike was sold on again, to another owner, who promptly dismantled it again, for another restoration that never happened, losing and breaking some parts in the process, before being further sold on as a basket case again, to another new owner who has resumed the restoration project. Yet again, further parts of 187 ENK have subsequently been back through the workshops, so progress is seemingly on-going.

This typically illustrates what can seem to happen with a number of bikes, which for many years may go through a tragic series of non-restorations that often seem to leave them in a worse state than they arrived. In the case of this bike, IceniCAM workshops has played an on-going contribution towards this particular machine for quite a number of years now, and we can only hope that it successfully emerges from the ‘restoration tunnel’ again someday.

Probably a nice thing about ENK is that it has now returned to ownership just a few miles from where its 54 year journey started at Radlett—local bike returns home!

OCT 893 was another AV78 that came through the workshops among the same ‘job lot’ as ENK. Again, this also went through registration recovery, returned to running order and shortly sold on. The motor subsequently returned to the workshops for service and tuning work, ever since which the bike has remained in fairly consistent use by owner Lindsey Neill at Hatfield, attending occasional EACC rallies. The road test and photoshoot on OCT were completed in March 2010, so gives some idea how long this feature has been marinating in the can, waiting for the final piece of the jigsaw...

Old Rusty, KPV 684 only completed rt & ps in August 2012. The original intention being to do all three bikes together, and probably present the article sometime back in 2010, but ‘we missed the bus’ so to speak, when this final machine disappeared into ‘deep storage’, so we just had to play the waiting game ... for 2½ years!

By this time, the idea of presenting a ‘French’ edition had hatched ... we obviously wanted to include some iconic Mobylette feature, and the AV78 sequence seemed to fit the bill.

KPV was another ‘local bike returns home’ when owner Laurence Coates brought it back to Ipswich from Norwich some 10 years ago. Once again, all engine modifications were completed through the workshops, and illustrates just how durable these tuned motors can be, since the bike has remained operational for the following decade without requiring any further work.

Once again, though the workshops variously invested a significant amount of time into all three machines presented in the feature, actual production cost of the AV78 article was quite negligible since all bikes were incidentally tested and photoshot as they passed through. Sponsorship became aptly credited to fellow AV78 owner Denis Bishop at County Down in Northern Ireland, and shows just a small contribution goes a long way at IceniCAM.