Sometimes stories don’t so much start from a fixed point, but may develop from a chain of events.

Before the autocycle in Britain, there was the autocycle in France—but over the Channel the equivalent machine came to be called the Vélomoteur. You may recognise a number of similarities, and a number of distinctive differences too.

The French Circulaire 32, Série B of May 1926 introduced the Bicyclette à Moteur Auxilaire (BMA) specification: under 30kg, less than 30km/h performance, below 100cc capacity and fitted with pedals, to qualify for exemption from registration. Effective from the age of 14, the classification neither required a driving licence nor testing or tax, and the order became effective on 12th September 1926.

In the ‘roaring twenties’ though, there wasn’t really enough significant uptake to produce machines compliant to this new specification. Small capacity engines of the time were fairly ineffective and not particularly commonplace, and people who could afford to buy motorised vehicles would invariably invest in a more capable motor cycle or car.

Towards the end of the ’20s however, circumstances would bring dramatic change to the world economy.

A fall in American share prices began around 4th September 1929, and hit worldwide news with the US stock market crash of 29th October 1929, infamously coming to be known as Black Tuesday. This became the origin of the most severe commercial downturn of the 20th Century, subsequently adopting the title of The Great Depression. The timing of its impact varied, and affected different nations to a greater or lesser degree, but most countries started to experience the ripples in 1930.

The Great Depression had devastating global effects, compromising both the rich and poor alike. Business profits plummeted, commodity prices dropped, personal income and national tax receipts fell dramatically, and international trade was more than halved. Unemployment in the US increased by 25%, and even up to 33% in some other affected countries.

Economies based on heavy industry were particularly hard hit and construction practically halted in many countries, while communities in rural areas also suffered as crop prices fell by over 50%. Plummeting demand for practically all products decimated many primary sector industries, particularly mining, logging, and cash-crop farming, which all shed labour at a crucial time when there were few alternative jobs.

By 1931, France was gripped by the fist of economic depression but the country’s high degree of self sufficiency somewhat cushioned the effects that were having a far greater impact on its European neighbours.

Looking at the changing situation, Peugeot designed and launched its first Bicyclette à Moteur Auxilaire in 1931, to better suit market demands of the time for small capacity economic transport.

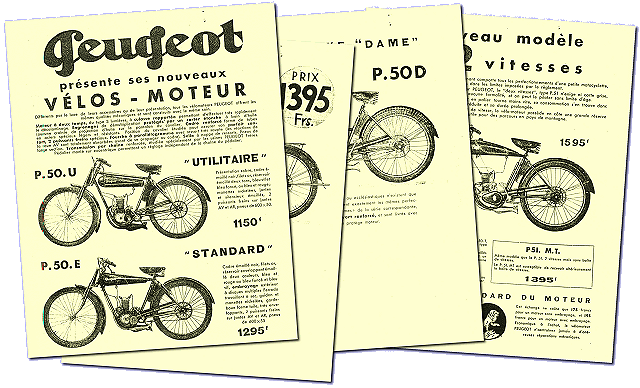

The first 98cc BMAs appeared as two introductory models with stirrup brake sets to comply with the specification on 30kg weight and 30km/h performance, the Utilitaire P50U with 600×50 tyres, and Standard P50E with 600×55 tyres. There were further minor differences between the types in fuel tanks and finish detail, but were clearly derivatives of the same base machine. Period adverts starkly illustrate how minimalist these machines really were, with no electrical generator and no lighting set.

Peugeot presented their new BMA specification motorised cycles, calling them Vélos-Moteur, which translates as ‘Moped’, later destined to become adopted as the generic name for small pedal assisted machines.

Our first vélomoteur seems to be a Modèle Luxe P50T, though the model stamping suffix is difficult to make out on the frame plate. Utilitaire ‘U’ (1,150 francs) and Standard ‘E’ (1,275/1,375 francs) versions were only fitted with basic stirrup brakes at both front and rear, where the Luxe ‘T’ (1,475 francs) offered the relative excellence of two hub brakes, and this example can be dated as 1932 from the size of its brake drums and distinctively rounded pattern of fuel tank.

Frame serial is 15128, with matching serial on the engine plate, and motor indication as P50 type, since at this time the same engine was fitted in all three models.

We think Peugeot probably continued the frame serialisation across all their vélomoteur models, so the progressive numeration should give some relative indication of the dating and the total quantity made.

Just handling our machine would appear a little heavier than expected, so we put it on the scales, and ... 5 stone 4 pound or 34 kilogrammes, so it seems to have put on a few pounds over the years! Even allowing for addition of the rear stand, carrier, number plate and some fuel in the tank—we wonder if the Luxe might barely have met the 30 kikogramme specification? Perhaps only the original stripped down basic models did, and the additional heavyweight brake hubs may never have been accounted over and above the lightweight stirrup brake sets?

The motor certainly looks very ‘old school’, with a large cast iron external flywheel and ignition provided by a gear driven Sociètè des Magnètos RB magneto (Robert Bosch–Paris). The top of the magneto drive casing is topped with a prominently placed grease nipple, which appears to be the intended means of lubrication for the gear train, and suggests this section of the engine being isolated from the crank chamber.

Cooling fins on the iron cylinder and aluminium head are both pretty minimal, but presumably adequate at the expected low operating revs of a plodding deflector-top design with single transfer port.

The carburettor is a 16mm Gurtner, but the intake is restricted to 10.6mm diameter by a control plate. It’s obviously meant to be like this since the choke shutter wouldn’t be at all functional if the plate were removed. There is no air filter, just an intake cover plate since the carburettor is forward facing and you’d probably want to deter at least the worst objects from being sucked into the motor.

Single speed drive from the motor transmits through a small dry-plate clutch on the output shaft, with final transmission by chain.

There’s little in the way of any excessive engineering to the rigid cycle chassis, the girder front fork set is dainty and lightweight, but the brake hubs may appear larger than might be expected for a machine of such limited performance—the efficiency of these vintage hub brakes could often prove disappointing in operation, so maybe Peugeot decided their new Luxe customers needed to see they were getting something significant for the extra cost above the stirrup braked base models, or maybe they just built them with some existing light motor cycle brake hub?

As early vélomoteurs didn’t come with the addition of a fitted stand, for practicality our example has been retro-fitted with a later sprung type cycle stand mounting off the rear axle, though this isn’t particularly recommended for starting since the bike tends to roll off it quite readily, so we’re going to opt for the original style starting method by pedalling down the road.

Having no neutral gear, navigating the bike requires either the clutch holding in (there is no griplock latch on these machines), or the decompresser lever pulling in to enable the motor to turn. Neither proves particularly effective for wheeling the bike about since the clutch tends to drag, and the decompresser doesn’t freely vent enough capacity, so both methods probably involve more pushing encouragement than you may like. It’s easy to become impatient with such relatively slow progress, and we invariably lift up the back wheel by the rear carrier to whisk the bike around instead.

The petrol tap is located toward front left of the tank, push for on, latch across the delicate little choke lever to strangle ... are we tempted by the flood button on the top of the float chamber? It’s a cold day so, yes, just a little tickle for good measure.

You need to hold in the decompresser lever to get the engine spinning, though it also helps to pedal away with the clutch in to build up initial momentum, but both these levers are on the same bar and will require a bit of multi-tasking from your left hand. Three levers are disposed around the left grip, with the (reversed) front brake ahead and clutch lever underneath so you can operate either of these with your grip, and decompresser lever behind, which can be held by your thumb.

The right bar mounts the lever throttle control and rear brake.

Pedal away, once you’re moving, drop the clutch and the engine turns, release the decompresser and keep pedalling ... tweak a little throttle on ... the motor chugs readily into life ... ease on a little more throttle and trundle slowly down the road at a moderate walking pace before pulling in the clutch lever and easing to a stop on the front brake.

Now we need to open the choke lever down on front left side of the motor, while still holding in the clutch with our left hand ... ah! There’s only so much one-handed multi-tasking that’s possible, and you can’t reach the choke lever with your right hand. Yeah, how does that work?

You can’t release the clutch lever or the engine will stall, so we end up leaning across the bike to transfer the clutch hold to our right hand, so we can now reach down to latch off the choke lever ... which instantly clears the motor and the revs run away, so quickly sit up and transfer the clutch back to your left hand so you can reach back to ease the throttle lever down with your right. Interesting piece of design that control arrangement! Perhaps there’s some easier way, but it’s not obvious! (Maybe step off the left of the bike while still holding the clutch lever in with your left hand and steadying the bike, then your right hand remains free to work the choke and throttle control ... though there may be other hazards in that method if you accidentally release the clutch lever—the bike could leave without you!)

Anyway, here we are, in the road with the engine running off choke, holding in the clutch and ready to go, with our pace bike rider nodding slightly and glancing encouraging looks through his visor slot, so pedal assisting away while feeding out the clutch and easing on the throttle, we get underway.

Very typically of deflector-top scavenging, there’s adequate torque from low revs and our vélomoteur pulls steadily with a plodding acceleration along the road to the first junction, where we tentatively feel the brakes to gently ease down the initial pace, almost to a rolling stop—all clear, then throttle away again up the lane.

The exhaust produces a firm barking note under load, loud but not overly intrusive for such an old machine. We’re very doubtful this is the original exhaust system, but the bike gets away with the noise because of its age.

You don’t get very far before realising there isn’t going to be much prospect of achieving any real speed, as the build up of revs quickly flatten out to a staccato firing sequence, and that pretty much seems to be it! The throttle fails to achieve any more response other than regulating noise from the exhaust, and very much feels that the motor is running out of carburetion from the control plate regulating the intake. The motor would probably run quicker if the intake were modified, but at least it stops risk of the engine being over-revved and probably serves well to avert mechanical disaster.

Glancing back to our pace rider, the eyes through the visor are saying "come on then", but that’s all we’ve got for now ... maybe pressing on to get the engine hot will enable a little more? By the time of turning onto the main road, we’ve got to be well up to temperature now, so open up the throttle out of the corner, crouch down as much as we’re safely able and give it the beans up the straight ... there’s lots of noise, and vibration ... it seems as if the revs are slowly creeping up ... going through the vibration, still lots of noise from the exhaust ... we’re giving this everything now, nearly maxing out—then our pace rider pulls up alongside "OK, it does 17mph, that’s it, let’s go home".

Well it felt faster, and we were really trying!

Handling wasn’t anything we felt particularly inclined to exploit considering the limited performance, so the short ride is probably best described as cautious and unsteady. The front suspension seemed to have little discernable effective operation, and most of what cushion effects there were would probably be more attributed to the saddle springing and tyres. The brakes proved adequate for the performance, though that wasn’t much of any challenge at such lowly speed, and on any normal scale we would probably be deriding their poor operation.

We probably expected worse from the dry clutch, since these primitive mechanisms can often drag when pulled in and slip under load, but it actually worked quite well once the engine was running (though our workshop had just overhauled the unit prior to the trial run).

The worst aspects were undoubtedly difficulty of the control arrangement, and suffering the restricted performance (30km/h = 18.6mph), where it would be tortuous even thinking of travelling much distance at such a miserable pace—though it may seem an improvement to the physical effort of cycling?

From the initial two vélomoteurs in 1931, then three models in 1932, the success of Peugeots BMAs was becoming quite apparent, as the advertised range doubled in 1933!

The Utilitaire, Standard & Luxe were now joined by a step-through frame model with engine guarding, Modèle Luxe “Dame” ou “Ecclésiastique” P50D (1,425 francs), for ‘ladies’ and ‘gentlemen of the cloth’, a nouveau modèle à 2 vitesses P51 (1,595 francs) two-gear model, and P51MT. In a strange quirk of French marketing, the P51MT ‘Monovitesse’ modèle was offered for 200 francs less, and listed as a single-speed clutched version with the option of conversion to two-speed by fitment of a gearbox, presumably when the owner might afford one later!

The two-speed P51 was formally presented in 1933 with a new ‘flat-bottom’ tank, which was also fitted to the Luxe P50T of that year, but ‘early production P51 models’ seem to have been developed and introduced during later ’32/early ’33, which is what we appear to have as our second feature machine.

This early P51 model is characterised by the same distinctively rounded pattern of fuel tank as fitted on our earlier 1932 Luxe P50T, and there’s a brass plate displaying 1932 on the left hand chain guard, so somebody else has obviously thought it’s from around this date too.

The frame plate identifies our model as P51T, and serial 40249, so appears that Peugeot had produced some 25,000 vélomoteurs within the year since our first featured machine—which is a pretty staggering achievement when you consider they managed to accomplish this right in the middle of the world’s worst recession!

Though the P51 seems to be based around the same BMA chassis and general cycle components, its two-speed transmission rather suggests it might be expected to perform a little better than the P50, otherwise why have two gears for a machine that would only need one gear to do just 30km/h? One may conclude that the two-speed P51 might be unlikely to comply with the restricted performance BMA specification, but Peugeot’s period literature states "This new machine, which now includes all the improvements of a small motor cycle, remains within the limits imposed by the regulations … and like all other Peugeot vélos-moteur, does not require registration card or driver’s licence, or any formality and can be ridden without any age limitation".

Peugeot’s literature went on to particularly emphasise advantages of the two-gear transmission for hilly conditions, without any hint that it might go faster than the 30km/h BMA specification ... so it’s going to be intriguing to see quite how this works out.

After our first P50T test, we’re also becoming slightly sceptical about the 30kg weight compliance anomaly, so sticking our two-speeder on our imperial scales—it weighs in at 6 stone or 38kg! Another vélomoteur that seems to have put on a few pounds over the years! OK, there are a few litres of fuel in the tank, maybe if you took off the rear carrier and stand; and does the front lighting set count? No, let’s face it; you’re still not going to lose 8kg are you?

Compared to our previous P50 Luxe, it’s particularly noticeable how small the front brake hub has suddenly become: just a tiny little brake plate that looks like some miniature shoe polish tin rather than anything convincing to actually stop with!

Everyone calling by the workshop seemed to look at this machines and go ‘Oh, that’s nice’, well, you can see the appeal maybe? The bike looks almost as though it’s grown naturally into itself.

Over a period of some 80 years this machine has developed the striking character of a diminutive vintage flat-track racer, but as we know from our first vélomoteur to BMA 30km/h specification, the impression can be deceiving, and these things may be nowhere near as fast as someone may presume.

With a bike this old, that has presumably had significant use over the decades, there’s going to be a lot of things worn out, rusted away, fallen off, been bodged and changed, until you really have to wonder how much of the original machine remains.

Both chain-guards are home fabrications, the petrol tank seems to have more fibreglass in it than a kit car, front mudguard is made out of bits, the rear stand is a crude improvisation, we presume the leather saddle to be a replacement, the exhaust pipe seems to have been welded from odd bits of tube, and though the silencer appears much the same as on our previous machine, we’re fairly doubtful of it being the original system.

The carrier is a retro fitted cycle rack, and none of the brackets seem to close their clamps properly so the gaps have been made up with various leather/rubber/fabric packers ... it’s like a something that has been cobbled up for all its life by people who seemingly knew little about motor cycles or engineering.

Some might call this ‘character’, but we’d probably call it ... a death trap!

We’re presuming the frame and engine to still be original, and it’s probably nothing short of a miracle they might have survived this long against all odds of the various owners and bodgers that have left their marks over the decades.

The motor on our P51 is markedly changed from the P50. The crankcases are different, and mount a dainty two-speed gearbox on a little platform behind. Primary drive is by exposed chain, with a heavier gauge dry clutch, and the P51 introduced Novi mag flywheel ignition to replace the magneto. At first glance, it appears that it has the same skinny-fin top end, but no—the carburettor is rear facing so it’s a different cylinder casting, and the carburettor too is changed to an Amal, which does seem to be original fitment!

The Amal appears to be a similar bore to the Gurtner on our Luxe, except that the intake on our two-speed P51 doesn’t have a restrictor plate, and the choke shutter is fully sized to strangle the bore, so certainly doesn’t appear to have ever been governed down to BMA specification.

The gear-change lever conventionally mounts on the right hand side of the fuel tank, so you have to take your hand off the tiller to shift ratios. A rod linkage connects down to the tiny two-speed grease lubricated gearbox, click forward for first back for second, and neutral between. Selection is surprisingly delicate and lightly engaged by simple external indexing, though it does seem possible to overrun the selector plate since it appears to have no positive end-stops, which apparently results in further false neutrals at both ends of the box.

Also on the right bar, the throttle is lever controlled, and again reversed braking, so the right lever operates the rear brake.

The theory in reversed braking is that your right hand is going to be more free for brake operation, and that you’d rather be stopping with the rear brake than the front if conditions might be poor (wet or slippery). Once you’d managed to pull in the clutch, change out of gear and into neutral, and released the clutch, you could then start using the awesome power of the ‘shoe-polish-tin’ front brake in a fully controlled manner.

This front brake is simply amazing in that you wouldn’t believe that such a miniature drum could function at all! We give it a try, and no—it doesn’t really! You can pull on the lever and still push the bike forward with relative ease, so laying a calliper against the brake plate we figured the drum would probably be less than 70mm maximum.

The rear drum looks a little larger, and the calliper test suggests this might even be as big as 90mm, but the same push test with the rear brake lever pulled hard up to the handlebar fails to observe any effect at all, so the front brake is by far the better of the two—which is probably going to make the test ride interesting...

The left handlebar cluster mounts a similar lever arrangement to the P50 Luxe, with (reversed) front brake ahead, clutch underneath at 45°, and decompresser below at 90° which works an open-venting valve in the alloy head.

Where all P50 controls were awkward to use because they were widely spaced over 180°, the P51 controls are awkward to use because they are too crowded together over 90°, and particularly difficult for a rider wearing gloves—so cramped in fact, that we consciously chose to perform a bare-knuckle test run to enable better management of the controls.

To suit the P51’s rear mounted carburettor, the fuel tap position is relocated under left side rear of the tank, push on/push off, though which way it requires to be isn’t too clear until we notice the carb has started dripping—so that’ll be the right way then!

Choke is a shutter that flips across the air intake, and there’s a flood button to the float chamber. Though we figure the drippy Amal has probably got enough fuel already, we give the button a little dabble in the hope it might settle the needle valve and clear the flooding problem.

The engine has a deflector top piston with just a single transfer port, but in the lower part of the motor the primitive and basic design really begins to tell its age.

This far back, there are no crank seals as we know them today! These old motors normally relied on a copious dosage of heavy mineral oil to gummy-seal gaps between the main journals and their casings, so they aren’t usually particularly suited for running on thin and modern low-dosage semi-synthetic oils which would invariably fail to maintain the crank sealing. This example however, has received a motor conversion to fit modern crank seals, so is capable to run modern fuel/low-oil mixtures, which may provide some improvement upon the original expected performance.

As few of the P51 controls seem conveniently placed for effective operation, our unfamiliarity with the arrangement can be reduced by accepting that it’s going to be practically pointless even pulling the completely ineffective brake levers at all, consequently we decide to ignore the brakes completely and reduce complication to just managing the ride. It’s merely a matter of being prepared to slow down gradually by closing the throttle and engaging the lower gear.

Ordinarily a rider might pedal one of these to start, but the rear stand is a wobbly useless prop that can barely even hold the bike up, so we probably wouldn’t want to try it on the stand. It might come down to pedalling up the road ... except that the weedy pedal arms have been brazed with replacement eyes when the threads have presumably gone, so a stem of celery probably has more structural strength—pedal this hard, and they’ll just bend like liquorice sticks!

It also proves very easy to foul the mag flywheel with your right foot when trying to pedal, and the only real way to prevent this is not to pedal with your instep, but the ball of your foot instead, so your toes don’t stick out and hit the flywheel—it’s really not very well arranged.

The motor would probably have originally worn a magneto flywheel cover (probably spun aluminium), and it’s very likely these covers must have frequently suffered boot damage when pedalling, and the open clutch, primary drive chain and sprockets on the left side would be something you might not want your trouser leg getting caught in either.

Since it’s so easy to foul the magneto flywheel with your foot when rotating the pedals, the rider may shortly adopt a riding stance with the right pedal back, however there seems to be another inbuilt solution ... the left hand pedal disengages against a spring and can be rotated 180° so both pedals dangle down together like swinging footrests—so this wasn’t any idea invented in the 1970s on sports mopeds!

Realistically, these two-speed vélomoteurs would seem more likely to have been push started in gear. The switchable swinging pedals are probably a clue as to how the model was intended to be ridden in ‘footrest mode’, otherwise why have the feature at all?

In the same manner as some sports mopeds would be designed with switchable pedal/footrests in another 40 years time—the P51 used exactly the same means of getting round the BMA specification/regulation of its own day! Since P51’s pedal set is a clumsy and difficult thing to operate and not easily practical to switch back from dangling footrests to pedal, and because the two-speed gearbox meant the bike wouldn’t generally be requiring much pedal assistance, it’s most likely these two-speed vélomoteurs were normally permanently left in ‘dangle footrest mode’ and the bike simply push started.

We could pull in the decompresser, shove the bike down the road, hop on, drop the clutch and paddle along with the motor turning over, but there’s a fair chance we could be playing that game all day trying to get it to start ... so let’s cheat, with our very own Peugeot patent electric starter kit!

No, this isn’t quite one of the official period accessories … what we need is an extension lead, electric drill, 21mm flank-drive socket and driving spindle, then plug this onto the magneto centre nut, pull in the decompresser and press go. The drill cranks the motor over, drop the decompresser and keep the power on ... there’s lots of occasional coughing and banging, intermittent firing attempts, try it with choke, without choke, there’s a real trick to getting the engine to catch, keep the power on and open the throttle, and finally the motor picks up— and there you are, electric starting for a reluctant vélomoteur, no physical effort involved!

If you might have been expecting something pleasant and docile, it’s surprising how aggressive this vélomoteur engine sounds, not at all what you may expect from some docile antique autocycle, the exhaust has a sharp barking crack to it, and that silencer really doesn’t sound as if it has any baffling material inside it at all!

The dry clutch works OK, but changing gear requires taking your hand away from controlling the lever throttle and there’s quite a tendency for the motor to die out if you shut it right down, or rev up when you pull in the clutch if you haven’t shut it down enough. Since we know the shift can overrun its gear gates, we expect it’ll be quite rare to manage any competent changes, so our best policy is to try and maintain whatever speed we might controllably manage within second range, endeavouring to anticipate and judge the pace to minimise any down changes as much as possible.

With difficult controls and no brakes, our P51 certainly isn’t going to make a practical town bike!

The gears click daintily into first, neutral, second, or false neutrals at either end of the box, so it really proves quite easy to make a blundering incompetent mess of the seemingly simple task of selecting the two drive ratios, while our pace rider looks scornfully upon our difficulty.

The control operation and acceleration performance are nothing like the angry sounding impression of the exhaust tone, and gradually working up the pace in second (top) to acclimatise a feel for the rickety and vibrating cycle frame, we progressively build toward cruising speed at full throttle. On the flat, in still air and sitting upright, 23 to 24mph, at which the motor pulls along with a loud drone interspersed with crackling phases of staccato four-stroke firing.

With a thoroughly hot engine, best on flat in full crouch, 28mph.

The ride was done without gloves to ease access to the control levers, and it has to be said that vibration was quite evident. Now we can figure how many of the original parts probably went missing from this bike—they shook off down the road!

This Peugeot has no lighting generator coil in its mag-set, but it does have a cycle headlamp ... powered from a tyre driven dynamo! There is no rear lamp connected to this set.

If you we’re going to ride one of these in the evening, we guess you’d be hoping for a night with clear skies and a good moon!

The horn is a squeezy bulb hooter that doesn’t have much hoot.

The rigid rear frame, and tired girder fork pivots gave a hard and unsteady ride, making the bike pretty difficult to manage controllably. It handles like a crate, and doesn’t stop in any way. Basically it’s an accident looking for somewhere to happen, and hardly seems fit for use on public roads in its present condition—though UK law now says that any vehicle made before 1960 doesn’t require MoT test! Maybe, 80 years ago when the bike was in better order, and in the empty French countryside you might generally have got away with riding one, but if you were thinking of relying on one of these for transport today—you’d be better taking the bus!

Most of the general world economy had pretty much bottomed-out in the recession by 1933.

The two-speed P51T was formally presented in 1933, with a new ‘flat-bottom’ tank, and continued in the same format for 1934, with the same range of models.

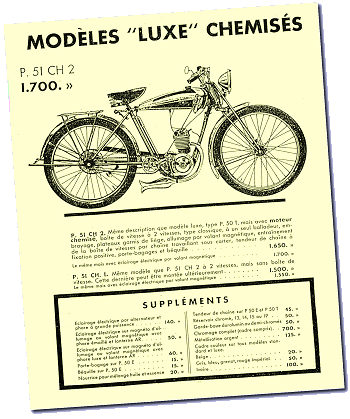

1935 introduced a revision of the two-speed version as a new Modèle “Luxe” Chemisé P51CH2 (1,650 francs base model), with larger finned head and barrel, where the capacity was now advised as 100cc, and carburettor remounted off left of the cylinder.

Both P50 and P51 Luxe models now came equipped with rear carrier and stand, and presentation of the Modèles Chemisés was accompanied by an extensive list of suppléments, including lighting equipment, chrome plated parts, Duralumin chain guard and paint finish options ... sure signs that an aspirational French society was emerging from its depression years.

We also have one of these 1935 P51CH2 models available for comparative examination, but it’s a non-running machine, so we are mercifully spared the opportunity to ride this example.

The BMA vélomoteur proved to be the right product at exactly the right moment, and pretty much saved Peugeot’s engine equipped cycle sales at a time when general motor cycle sales were badly compromised by the economic climate.

The original Utilitaire P50U model was dropped from the range in 1936, and the Standard P50 delisted in 1937, as Peugeot’s whole vélomoteur range received an upgrade to reflect the recovering economic climate.

With the original external flywheel BMA engine now gone, the new Modèle Chemisé “Standard” became the base machine, with Modèle Monovitesse Luxe P51CL1 next up the range. The step-through Modèle Dame Chemisé “Standard” P51CD1 was now joined by a new Modèle Dame Luxe 2 Vitesses P51CD2 (two-speed model for ‘faster’ ladies), and Modèle 2 Vitesses Luxe P51CL2 (for more luxurious gents).

Dropping the utility base models and upgrade of the range was really underlining the fact that France was now well through the depression.

1938 found P52CHL and P52CLK2 models with a new ‘motor cycle style’ rigid frame, kick-starting, and footrests instead of pedals. Peugeot’s old vélomoteur looked to be evolving into a more modern 100cc, two-speed motor cycle.

While some economies started to recover from The Great Depression by 1935, for many countries its effects typically lingered toward the later 1930s and even into the early years of World War 2. Then everybody had other problems.

On 10th May 1940, German forces began their invasion of Holland, Belgium, Luxembourg and France, sweeping south across the country. On 10th June, Italy invaded France from the south east and, twelve days later, France surrendered, subsequently becoming divided into German and Italian occupied zones, and the Vichy state.

As with autocycle production in Britain, the transition to war compromised manufacture of Peugeot’s remaining vélomoteurs and motor cycles.

A French Vichy government decree of 5th June 1943 technically re-defined the original Bicyclette à Moteur Auxilaire (BMA) specification into three newly qualified motor cycle categories as Motorcyclette over 125cc, vélomoteur between 125cc and 50cc, and Bicyclette à moteur de secours (later called Cyclomoteur), under 50cc.

Defining the new 50cc category for even smaller motor assisted cycle engines had probably been initiated by improvements in the efficiency of engines making even smaller capacities more capable for economic transport.

Like the introduction of the earlier British ‘low taxation–under 150cc’ class in 1931 to promote economy vehicles during the depression years, there wasn’t really anyone particularly manufacturing sub-50cc motors in France during the war years, but once occupation ended and the country began to resume business, then the category would be set for adoption.

France’s liberation would not even begin till D-Day on 6th June 1944, by which time Aldo Farinelli was already into developing his 48cc ‘little pup’ Cucciolo prototype, which was yapping around the streets of Turin later in the year. Italy’s liberation came ahead of France with the technical ending of hostilities dating from signing of the Allied Armistice on September 3rd 1943, though parts of Italy were still not freed from German control until April 1945.

Even before the end of World War 2 it was becoming evident the new European ‘economy capacity’ was going to be within the Bicyclette à moteur de secours category, and sure enough, following the war and driven by the urgent demand for economic transport, sub 50cc motors began popularly appearing across Europe in pedal assisted cyclemotors and mopeds.

Having been in the motor vehicles business since the very dawn of the petrol engine, Peugeot experience appears to have placed it as one of the ‘smart manufacturers’ who always seemed to instinctively know when to get into something new, and the right time to get out again when the moment is passed. While a number of other French manufacturers presented various post-war vélomoteurs within the new specification, Peugeot never resumed any of their pre-war vélomoteur models.

They already knew the future was moving on to the moped.

The BMA vélomoteur had its brief day in the climate of The Great Depression, and while the initial Utilitaire and Standard P50 basic models with lightweight calliper brakes were undoubtedly built to comply with the original weight and performance restrictions, we think the later Luxe and two-gear P51 probably started ‘pushing the boundaries’ of the BMA technical limitations, subsequently resulting in the redefinition of the categories by 1943, since developing vélomoteur performance had already left the obsolete BMA specification back in the days of The Depression.

All the BMA specification seemed to establish was a free-for-all unregulated motor vehicle category, which many of the vélomoteurs subsequently failed to technically comply with, but was completely impractical to officially manage or police.

French decree 1189 of December 11th 2003 introduced registration effective on all new mopeds, and stated that all old and mopeds would need to be registered by June 30th 2009. This deadline was later extended to December 31st 2010.

In France, young persons can still ride a moped from the age of 14, but are required to complete a BSR course (Brevet de Sécurité Routière), which consists of a theory paper ASSR1 (Attestation Scolaire de Sécurité Routière) taken at school, and five hours of practical training, 4½ of which must be on public roads with a driving school (at a cost of around €75).

French motor cycle licences will be changing from 19 January 2013 and a licence will be required to ride a moped. The old BSR will be superceded by licence category AM. Obtaining an AM licence won’t be much different from the BSR—the duration of the practical training increases to seven hours.

Third party insurance is now required, and the insurance certificate is required to be displayed on the moped in a similar manner to a UK tax disc.

There are currently no equivalent MoT tests (CT– Contrôle Technique) for any two-wheelers in France, but it is planned to introduce a requirement for CT tests on mopeds in 2013, though not extending this to other motor cycles—which might seem rather puzzling, but primarily seems intended as a check to confirm mopeds will not be modified to exceed the specified limit.

French mopeds are still currently exempted from road taxation.

Next—Back across the English Channel, excavations in old Coventry unearth a strange and prehistoric industrial fossil.

Alerted by the government, IceniCAM engineers are called upon to assess the ancient relic, but to exhume this mechanical dinosaur may go beyond normal experience, and require the special skills of our extraordinary museum curator, Indiana Bones–Autocycle Archaeologist!

Could this be the missing link to all that we know today?

Our next main feature looks back to an ancient time, well before the first English autocycle in 1934, before the French vélomoteur of 1931, and even pre-dating when the French politicians thought to dabble with their BMA specification in 1926 ... to something dark, and long extinct ... lost and forgotten in barely recorded history, this is truly—a Living Fossil.

This article appeared in the

January 2013 Iceni CAM Magazine.

[Text and photos © 2012, 2013

M Daniels.]

All three of our featured ‘Vélos-moteur’

were on show at Copdock Show

this year.

For this article, the BMA P50T road test and photoshoot was only completed in early November, and text development on all articles barely even started until after the Kneel’s Wheels event in mid-November, when the last of a whole crowd of other road t & ps machines for future articles had finally cleared.

With publication timed to coincide with the Mince Pie Run, the 30th December date was slightly earlier this year since David Evans had mysteriously brought the event forward a week. This required all our printing completing over the Christmas break to enable magazines to go in the post for 27th/28th December, and working back required the magazine editing and laying up over the previous week, so the editorial deadline was set for 15th December—leaving just four weeks to finish all three articles from little more than test notes ... time to press the panic button!

Well, as you see, we made it ... but only just!

Vélomoteurs—The 1932, two-speed Peugeot P51 was actually the first vélomoteur we became involved with, when the wretched thing turned up at the workshops for ‘just getting running’—yeah right! If only life was really that easy!

Some aspects of these Peugeot motors were quite cheaply engineered, for instance there’s no bronze bushes for the case journals to run in, they just revolve in the plain aluminium—which is OK until things go wrong and people continue to run them ... like the main bearings go and the crank journals wear the cases, like the main journals run slack in the bearing cores and wear into the cases, like the main bearings turn loose in their housings and the journals wear the cases—or in this case, all of these things.

When they’re this old and had this much use—there really isn’t any crank sealing left anymore! The motor’s about as drafty as a string vest in a gale, and air seems to waft through practically every warped joint in the engine casing.

These old motors often get so bad that they require pushing at increasingly greater speeds simply to start, and just won’t run slow at all. Carburetion is ruined as air gets sucked in everywhere, and in this state they’ll require serious re-engineering to recover any prospect of future operation.

Our workshops built up a housing on the left-hand crankcase boss behind the front sprocket, to enable machining for fitting a crankseal, and the inside of the tight-hand crankcase was bored out to fit another journal seal on the inside. The motor can therefore now run on modern semi-synthetic oils—but this conversion probably isn’t the sort of work that many aspiring owners are going to be up to undertaking. Following what seemed an interminable period haunting the workshops, the two-speed P51 completed re-engineering, then rt & ps in July 2012, before finally returning to Suffolk owner Martin ‘Cally’ Callomon.

1932 BMA P50T from Luke Booth in Hastings only came in after the Copdock Show in October 2012, and yet another bike requiring more technical attention (ignition timing & carburetion) in the workshops to return to running order for the road test. Needs must, but we generally don’t like doing machine photoshoots this late in the year as photography gets rather difficult due to poor light, low sun angles, and long shadows.

Final vélomoteur in our set was 1935 P52 ‘Chemisé’ (a non-runner for illustrative purposes only), which has subsequently departed via Transglobal Shipping to new owner Geoffrey Clark in New Zealand. We just received news the container arrived at Auckland port over the Christmas period, so this bike is just about to start its new life on the other side of the world.

Despite a most considerable log of many difficult workshop hours to return these vélomoteurs to serviceable order for road test, the actual accounting cost for presenting the ‘French Lessons’ article was virtually nothing since all machines came and went via owners, transport. Sponsorship became credited to Mick Cousins, Suffolk Section EACC.