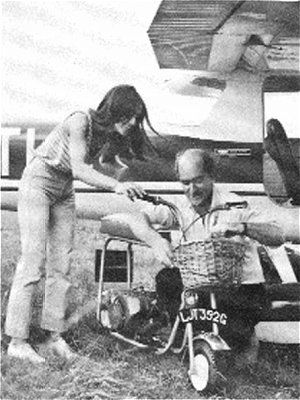

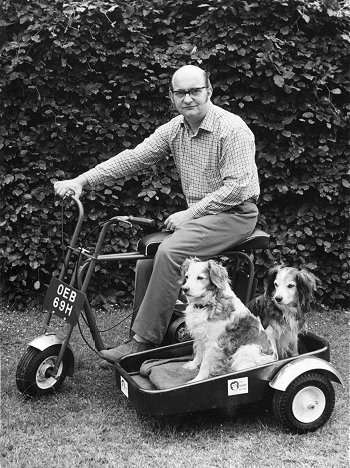

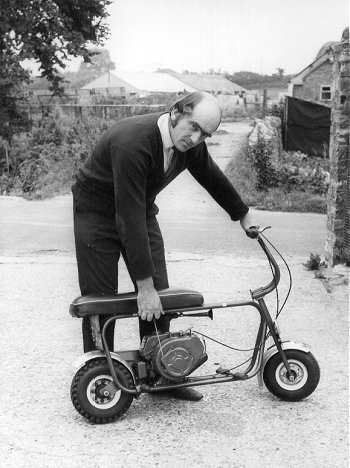

John Aley on a prototype sidecar Chimp

Mike Wood and I were both in our thirties and both coming to the end of our active racing careers. In the true Sixties' spirit we had both acquired light aircraft and both had come up with the problems of local transport at the destination when we flew anywhere. So when we had a long trip across France in a far from reliable Renault 16 we had plenty of discussion time and this subject took pride of place. Mike had a small agricultural engineering business in Dorset and already acted as my subcontractor producing the range of John Aley Rollover Bars which I had recently introduced with success to the market, so we were well equipped to fill this gap in the market.

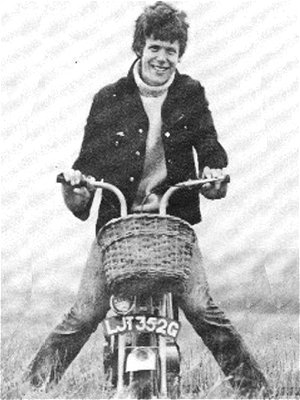

Mike Wood starting a MkII Chimp.

There was a real need, we decided, for a light weight means of transport, cheap for people who were still recovering from post-war austerity and bought everything on price so there was no room for fancy design. It must very simple but reliable as we intended selling to folk who would regard it in same way as their lawnmower rather than a motor cycle to be loved and cherished.

With memories of the wartime folding Corgi designed to be dropped with paratroops but one of which my heavyweight father in law had used for local transport around Silverstone going about his PA duties, we thought at first of something which would fold but rapidly abandoned that in favour of collapsibility so the various sections would be lighter to lift and easier to stow in odd compartments.

Unlike Honda who at that time produced a beautiful little wonder called The Monkey Bike we chose simplicity and reliability in the form of a 98cc Clinton two-stroke industrial power unit designed for chugging away all day on a building site driving a cement mixer.

Of course it had to comply with 'The Vehicle Construction and Use' regulations since it would be used on public roads and these rules required two separate brakes. This taxed us until I came up with the idea of a drum brake on the rear wheel operated by a conventional handlebar lever while a foot pedal brought a block on to the outside of the rear tyre. In practice this meant we could lock the rear wheel in two different ways but anyway the Authority said nothing about braking both wheels.

We discussed this while cruising on open French roads and whenever we stopped for refreshment the French paper table cloths provided me with a sketch pad which I filled with ideas that Mike in a more practical way could turn into metal. On arrival at Dover Mike headed for Dorset complete with the aforementioned table cloths while I hit the Cambridge road. Imagine my surprise when he rang me a few days later saying the prototype Chimp Go Bike (name with echoes of Honda) was not only built but worked and with typical Sixties' optimism, was ready for us to sell by the thousand making our fortune.

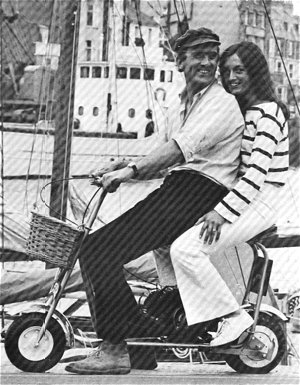

Sales were steady and we produced several hundred some of which still exist today. Many friendly journalists gave us valuable publicity and in fact one evening I was reading a magazine write up over supper in a French hotel and showed it to Le Patron who promptly went mad introducing me to all his staff and guests as the notable English motor cycle manufacturer who was gracing their humble establishment - I cannot recall whether this flattery was echoed in my bill next morning but there was lots of handshaking and free drinks during the evening.

Soon after its introduction we had a stand at the Cranfield Aero Show where we had half a dozen Chimps which we lent to the organisers and the members of a Naval aerobatic team, gaining us good publicity and lots of maintenance work for our newly arrived from New Zealand mechanic who had never seen anything like it in his native country.

Throughout the Chimp's three or four year existence we stuck to the original concept of a simple cord started stationary engine driving through a centrifugal clutch of our own design to the rear wheel which carried both brakes as mentioned above. Not seeking the ultimate in steering we accepted very small wheels for light weight and portability while to avoid the extra burden of Purchase Tax we sold the bike as a kit for £67-10s, with all the ensuing problems!

It was fun. Perhaps in retrospect we should have been more serious and realised that a new era was coming in when the public would pay extra for something less crudely engineered and we should have made more effort to sell into the boat and caravan worlds where the need for local transport also existed but on a greater scale and where despite not trying very hard we made several sales.

Even the end was amusing. We were losing our initial enthusiasm when after a few years someone came along and bought the lot but obviously thought he had good ideas for the bike's future as he wasted no time in telling us how he would not only change the complete design and marketing but the name as well. Without any qualms he paid the asking price, the cheque didn't bounce but in six months he was back asking for our help in selling the project on his behalf.