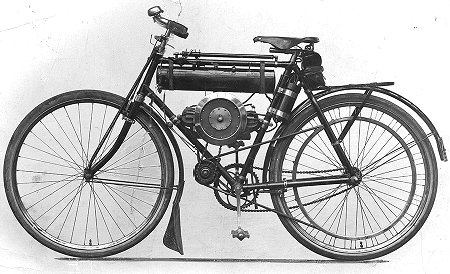

1905 Fée motor cycle

Fairy story is not a totally accurate title as the first horizontally-opposed twin-cylinder Barter engine motor cycles of any number did not appear until 1906 and were then called the ‘Fairy’. However, 1905 is the year under the spotlight when Joseph John Barter built his first twin-cylinder prototype horizontally-opposed engine and called it the ‘Fée’, which is French for fairy.

Joseph Barter’s main obstacle was finance as his first working single-cylinder engine designed to be attached to a bicycle had to be produced by a company and was short lived. He obviously had the creative ability and some knowledge of the internal combustion engine, as his second effort, again to be mounted in a bicycle had to rely on others and where he worked for machinery.

1905 Fée motor cycle

My findings lead me to the guess that the bicycle chosen to house his engine was French with its Latin named saddle. Joe possibly intended the 16 inch long engine to be sold to fit in existing bicycle frames but, at the running stage, had to admit that the building of motor cycles proper had overtaken his intentions.

We know that the engine worked alright after some adjustments to the distributor but the use of a round leather drive belt was not the right choice.

When I first decided to have a go at this replica I had some experience having constructed the CL38 two-stroke, but now I had to delve into the world of bicycles, of which I had little knowledge. A period of six months was taken up with the Internet, bicycle experts in the UK and America, eBay, and some knowledgeable members of the London Douglas MCC.

‘I then designed another motorcycle, a light machine weighing 60 lbs. The engine was twin opposed and weighed only 13½lbs. The flywheel weighed 6lb, leaving 7½lbs for the remainder of the engine. The cylinders were 2 3/16" bore and stroke and attained a speed of 20mph. This was the first time to my knowledge that a vibrationless twin opposed engine was used on a motor cycle. The drive was by a small chain from the engine to the counter shaft through a clutch enabling a large pulley to be used.’

‘As a result of a comment made on this model by a leading American manufacturer in 1906, I designed a more powerful engine which I called the Fairy. A company of Bristol men was formed and a large number of these machines were sold before the business was acquired by a London firm.’

‘I joined Messrs Douglas Brothers of Kingswood and was Works Manager for many years and consulting engineer until Douglas Motors 1932 was wound up. In 1910 the late Mr Ely Clark rode from John O’Groats to Land’s End and set up a new reliability trial record on a Douglas machine that I had designed. He was presented with a gold watch by Mr W Douglas Senior. And Mr Clark gave his helpers—Messrs Ball, Phillips, Haslam, Grout, Thornhill, and W W Douglas—silver cigarette cases to commemorate the event.’

Mr Barter who lives at Downend Road, Downend, Bristol confessed that his first attempt to design a motor car followed a visit to London when he saw one being driven in the grounds of the Crystal Palace.

‘At that time motor cars were not allowed on the roads. I said to myself: “I could make one like that” and I came back home and built an engine in my bedroom.’

Joseph John Barter

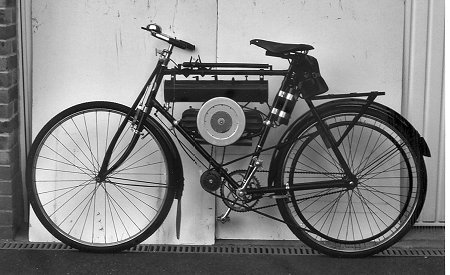

The first step was to construct the bicycle to resemble the one and only very sharp photograph that exists; at least for the CL38 two-stroke I’d had several photos and an article in The Motor Cycle magazine. Using the pump length and the wheel radius I was able to put together a list of approximate measurements to get a usable frame that would look one hundred years old. Time was taken up studying the photo for details as the make of bicycle became an obsession.

Distinguishing features were the chain wheel, pedals, saddle and the single brake lever working both brakes which none of the experts consulted recognised.

An enlargement on the scanner had to be used to try and read the saddle wording which turned out to be SIDURUM Latin for Star; there was a bicycle and parts manufacturer at the time called Star in Wolverhampton.

Experts ruled out BSA as they only produced parts at that time, although the machine was considered to be British by one observer and possibly French by another expert. So we have a bicycle possibly of singular manufacture or assembled using assorted parts, which was a common practice at that time with this new-fangled mode of transport.

The set up used stirrup brakes with plain handlebars, possibly of an older design.

Bicycle for the Fée project

So I offer this observation: Joe had a second-hand bicycle with rod brakes of the type that went on for many decades or a machine that had a front brake that stopped the bike by pressure on the front tyre, but stopping the machine needed both hands, so what did he do about the clutch and throttle? The handlebars were removed and replaced by a plain nickel plated older bar with no attachments and he obtained a single lever for both brakes which had to be clamped onto the handlebar stem. Being right handed the brakes were operated by his right hand, leaving the left hand for the throttle and clutch working on the crossbar. The chain wheel was so distinctive, which again nobody recognised, and was so like later American Schwinn designs but Internet enquiries led nowhere. At least the rat trap pedals seemed to be similar to the ones in a Star bicycle Internet site along with the carrier. A standard 24-inch diamond framed safety bicycle was found on eBay with forks for 28-inch wheels and was 70% complete. That suited me as I knew that there were parts needed of a special appearance. The wheels were rebuilt with new Westwood rims and all the bright work replaced for looks. To cover the distinctive parts, the next item was the chainwheel, which had to be created using a Raleigh centre with a special chain ring bolted to the outside.

The drawing I sent to Stenor Engineering in Shropshire was faithfully reproduced and went straight on the bike, having been nickel plated by Phil Jenkins. Brake parts were replaced with the same type still available as were the tyres, tubes and chain.

I could have had all the frame parts blasted but I was aiming for the look of a hundred-year-old bicycle that had been renovated and not straight out of the packet. Some small shallow knocks were left in and the mudguards left slightly stressed to try and give an air of age and the look of a prototype with odd paint chips touched in.

Pedals had to be reworked from Humber rubber block units which were stripped and the new metal parts added as an enlarged scan was reasonably clear. This showed that the pedals had a one sided centre plate and did not appear to have any pierced design work.

The handlebars, made by Ken Blake, were nickel plated and the Bluemel celluloid grips made by Vintage Grips went on with the period bell which is loud enough and the sort of thing missing on many modern machines.

The last item to complete the bicycle stage was the saddle, which was the traditional shape but had the unknown name to emboss, all very easy if you have done it before, whereas I had not!

200cc four stroke, horizontally opposed. Cam operated exhaust side valve, automatic inlet valve. Bore and stroke 2.3/16 inches. Cast iron barrels with no liners. Total loss oil lubrication from hand pump, 18mm spark plugs powered by twin ended trembler coil and wipe contact breaker. Battery re-charged off the machine. Surface carburetion, single speed, registration, AE 692.

The first item was the belt rim which, after some enquiries, was beautifully made by Dutchman Willem Pol, and then, after drilling, powder coated.

Barter had used a round section belt and found it a bad choice; even so, that was the shape used and made to fit straight onto the bicycle. At first I used a Singer sewing machine belt and, as the original was twisted leather, the size was increased to 10mm by a strip of chamois leather twisted on, glued and stained.

The pulley clutch would have been a problem if it were not for the help of Australian Graeme Gullick, who had an original pulley with his Fairy engine and had engineering drawings available.

I searched the Internet and decided on a small rope pulley in cast iron, which was bolted to a scratch-built clamp bracket made up from thirteen pieces to Graeme Gullick’s drawings. This is a Fairy period bracket with four bolts as the Fée item was a two bolt unit, which was obviously updated.

It was decided that the item under the saddle, strapped to the saddle stem, was the accumulator in a leather pouch, so a neat cover was constructed, then with the assistance of a local shoe repairer stitched to house the mahogany dummy battery.

The scratch-built clutch and throttle controls were mounted on the crossbar either side of the hand pump and resembled the type of lever found in a steam era railway signal box. The design was, for the period, very imaginative but again no one had seen that type of fitting before. ‘Joe’ Barter must have bought in many of the components as there appear to have been many parts manufacturers providing items ‘off the shelf’ at that time. Such items as the crossbar clutch and throttle levers, single brake lever, coil, oil pump, and clutch pulley which may have been intended for an industrial machine.

With one very good sharp photo of the near side I was mystified for a time by the existence of two cylindrical objects fixed somehow to the frame under the saddle, on the off side. I could only deduce that the front one, being one inch in diameter, was the oil pump, and the other. which was larger and seemed to have a cap, could be an oil reservoir. This proved to be true as the handle on the oil tap at the bottom of the pump was just visible past the coil.

Another mystery was the three possible filler caps on the fuel tank which we had assumed held petrol in the front and oil in the back. Eddie Turner came up with the observation that the fuel system was a surface carburetion tank, which was a system new to me, and all the odd control items on the tank, including the drain tap, turned out to fit diagrams found on the Internet.

It seems strange that a surface carburettor system had been chosen as it was considered by 1904 that this was too crude and a poor delivery method, followed by what we know as a spray system, the new and much more efficient method. Perhaps Joe had some parts from previous assemblies that helped cost saving.

Studying the photo on one occasion, I realised that there was a reflection on the tank which showed that the picture was taken outdoors and there where small trees in the background with no leaves and a bleak sky in early or late 1905, making Bedminster the likely place that the Fée was constructed and photographed. The houses in Luckwell Road (Lane) with ‘Braemere’ at number eleven were on the Eastern side of the road and the Western side was farmland, to become a school.

The barrels on the Fée were ‘one-offs’ in shape and the two plug locations are at different angles.

Fuel induction was by the familiar tubes with the mixing chamber of the surface vapour system in the middle, feeding from above as everything is out of sight on the near side photograph. Having looked closely at the ex-Kevin Hellowell Fairy in the National Motorcycle Museum in Birmingham I was able to identify that the Fée engine was supported by a curved pipe or rod running under the crankcase.

Taken late in 1905, the two machine photos we know of may have been taken when the project was finished with, and Joe Barter had realised by what he had learned, that the motor cycle proper was the next step.

I can only assume that the bike was black generally as, at prototype stage, the cosmetic angle would be left until a production project might be a possibility. The bicycle bright parts in the wheel rims, pedals and handlebar area would have been supplied plated. Noticeable, are the bright straps holding on the trembler coil which we can only assume were purchased along with the coil for fixing to tube work. The machine was legal having a registration number AE 692; the national system started in 1904.

The two main photos show a back number plate and the third photo with Joe Barter on board, which appeared in the November/December ’09 issue of New Con-Rod carries a front number plate as well.

With what I have learned in a two year period, I got the impression that, once the idea of a flat twin was decided on, Joe was in a hurry because he had to make use of where he worked and the various local establishments for castings and machining. Between 1904 and 1905 was the formative construction period and quite an expensive time for the build up of debts!

So here it is after two years, a copy of a prototype machine where an imaginative engineer learnt as he went along knowing what not to do for the time when he could make his efforts count to produce ... the Douglas.

The completed replica Fée

[Text and photos of replica Fée © 2010 Doug Frost.]