Queen Margherita’s crown tops Bianchi’s eagle

Born on 17th July 1865, Edoardo Bianchi was brought up in a Milanese orphanage and, at just 8 years old, started work at an iron foundry where he quickly began to display a remarkable aptitude for mechanical engineering. Edoardo trained as a coach builder (or fitter and turner in later engineering terms) and set up in a two-room workshop of his own, producing all manner of items from surgical instruments to electric doorbells. He started in the bicycle business by trading in penny-farthings, and then started a bicycle manufacturing business from a small shop at 7 Via Nirone, Milan, in 1885. At 21, Edoardo began to experiment with less unwieldy cycle designs than the early penny-farthings and tricycles and decided to concentrate on developing ‘safety’ bicycles by pioneering the use of equal-sized wheels.

The business moved to larger premises in 1888, where he produced the first Italian vehicle (a bicycle) with pneumatic rubber tyres, and subsequently fitted a front-wheel calliper brake.

Bianchi’s first pivotal opportunity came in the early 1890s when he was asked to teach Queen Margherita how to ride a bicycle, which in turn helped him to attract the business of Italian gentry (the only class that could generally afford to own bicycles at that time), and he was eventually given a royal appointment, allowing Edoardo to incorporate the royal crown on the Bianchi badge on every frame he made.

The business continued to expand apace during the 1890s as cycling became fashionable in Italy and further across Europe. In addition to bicycles, Edoardo tested a French De Dion single-cylinder engine mounted on a tricycle in 1897 and although it caught fire, Bianchi did become recognised as the first engineer to produce a motorised vehicle in Italy.

Bianchi’s cycling reputation was further enhanced when the company sponsored Giovanni Tommasello and he won the Grand Prix de Paris sprint competition in 1899. In the same year, Bianchi produced its first motorcar.

In 1901 Bianchi showed its first prototype motor cycle, which went on sale the following year. The production motor cycle was Bianchi’s first motor vehicle to be constructed entirely out of components manufactured within its own Milanese factory, including the 2hp engine, which was built under licence from De Dion–Bouton.

Technical developments and an increase in business resulted in the opening of a vast new plant in 1902, at Via Nino Bixio, Milan, which would now produce new motor cycle models, including a much improved single-cylinder model with magneto ignition, a leading-link front fork, and belt drive. In 1903 the factory was producing further engines mounted in the centre of strengthened bicycle frames, and by 1905 was offering other models fitted with a new Truffault design of sprung front forks. 1905 was also when the business was incorporated as Edoardo Bianchi & Co and, thereafter, turnover dramatically multiplied year by year as the company produced ever-increasing numbers of cycles, motor cycles and automobiles.

1910 introduced a brand new 498cc inlet-over-exhaust motor cycle model that was reportedly the envy of every other manufacturer in Italy and sold very successfully, firmly establishing Bianchi as one of the country’s leading motor cycle producers.

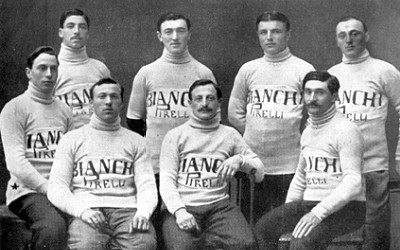

The 1911 Bianchi cycling team

It is claimed that Bianchi was making around 45,000 bicycles, 1,500 motorcycles, and 1,000 cars a year by 1914, but the First World War intervened and Italy was drawn into conflict against the Austro-Hungarian Empire. During the war years, Bianchi mainly concentrated on building aero engines, but also produced a 649cc V-twin engine in 1916 for a purpose-built C75 model motor cycle for the military. After hostilities ended, the V-twin engine was increased to 741cc and was also sold in a civilian machine. It was not until 1920 that Bianchi began to take an interest in competition events, when Carlo Maffeis, riding a 500cc OHV V-twin model, established a new flying kilometre world record of 124.9km/h (77.6mph) on a stretch of road near Gallarate. This attempt, however, was only partly funded by Bianchi, as the engine was prepared by Carlo himself at the workshop of his brothers: Miro and Nando.

For 1921 a smaller 598cc V-twin was released, along with a new 498cc single with all chain drive.

Il Campionissimo Primo

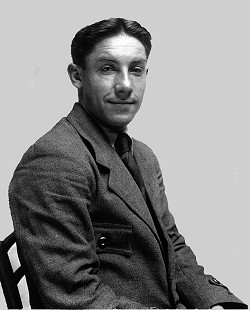

Campionissimo—oftem translated as ‘great champion’ or ‘champion of champions’—is the accolade the Italian cycling press and fans bestow upon the very best road racers. Constante Girardengo was the first to earn this title.

Constante Girardengo

Girardengo rode for Bianchi 1915–18 & 1922 and was ranked number one in the World in 1919, 1922, 1923, 1925, & 1926. His victories when riding for Bianchi were:

1915 Milano–Torino

1918 Milano–Sanremo

Serravalle–Arquata

Giro dell’Emilia

1922 Giro della Romagna

2nd stage of Giro d’Italia (Milano—Padova)

Giro dei Due Golfi

Tour du Lac Léman

Italian road race Champion

Giro dell’Emilia

Corsa del XX Settembre

Giro di Lombardia

In 1922 Bianchi sponsored Costante Girardengo, the first Italian cycle campionissimo, while at the height of his popularity, which is said to have strongly revived the company’s cycle sales.

There was a 348cc side-valve single for 1923, and another V-twin of 498cc. In 1924 a 173cc overhead-valve single was added to the range but, by the mid 1920s, it was becoming obvious that Bianchi’s motor cycle sales were being challenged by the likes of Moto Guzzi, and former employee Adalberto Garelli who had left in 1915 to go to Stucchi, before finally setting up his own motor cycle factory in 1919, at nearby Sesto San Giovanni.

In 1925, while a road-going 348cc OHV single was introduced, Edoardo decided he should promote Bianchi by going racing, for which chief engineer Mario Baldi designed a works racing 348cc single with DOHC driven by a bevel shaft and spur gears. The camshafts and coil valve springs were completely enclosed in sealed rocker-boxes, which was a rare feature in those early days, and it would become the most successful Italian racing bike in its class for the next five years. Named the Freccia Celeste (Blue Arrow), it was both fast and reliable, winning the long-distance Milano–Taranto, the Lario race, and the Italian Grand Prix at Monza. During this time these races were ridden by such riders as Tazio Nuvolari (who had started racing with Garelli), Amilcare Moretti, Mario Ghersi, Karl Kodric, Gino Zanchetta, Luigi Arcangeli, and Varzi.

Bianchi motor cycle team

including Moretti, Varzi & Nuvolari

Nuvolari first rode the Bianchi in the 1925 Italian GP, and won at a record speed, despite having started from last place on the grid with a push start and having his leg in plaster!

The 350cc double overhead cam Bianchi dominated Italian racing until the end of 1930, after which Baldi designed another 498cc OHC single-cylinder racing bike, which was successfully raced by further riders like Giordano Aldrighetti, Aldo Pigarini, Terzo Bandini, Dorino Serafini, Guido Cerato and Alberto Ascari.

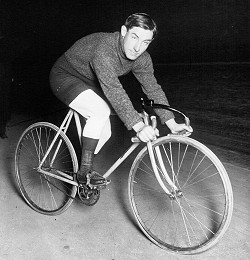

Nuvolari and his Bianchi 350

Bianchi bicycles were reportedly achieving sales of around 70,000 a year by the early 1930s.

In 1938 Baldi began design and development of a fabulous supercharged four-cylinder 493cc DOHC Grand Prix racer, to debut in 1939, but which would never reach its full potential because of the intervention of World War 2, and the FIM’s subsequent ban on supercharging.

Edoardo’s second great pivotal moment also came in 1939, when Bianchi adopted Tullio Campagnolo’s new gearing system, the Corsa derailleur, on its Folgore model. Operated with a rod, it enabled cyclists to change gears while in motion—much preferable to the previous system, which required riders to dismount and flip the wheel around. The Cambio Corsa meant its sales of racing cycles boomed in 1939—but only briefly, before political events brought about a close of play.

The Bianchi Company had begun building trucks in the 1930s and supplied the Italian army with vehicles during World War 2. Production was ended during the allied bombings of August 1943, when the Bianchi Motor works, its truck factories and warehouse buildings in the triangle zone between Viale Abruzzi, Via Plinio and Via Pascoli of Milan were practically all destroyed. Because the whole factory had been so extensively damaged, Bianchi was faced with the prospect of having to completely rebuild, but was then hit by a second tragedy on 3rd July 1946, when Edoardo died at 81. Control of the firm passed to Edoardo’s son Giuseppe.

By 1950 the bombed out Bianchi plant was rebuilt, modernized, and initially returned to production making bicycles. The new works occupied the same triangular site along Viale Abruzzi, with its office building on the corner to Via Plinio, just opposite the Basso bar. Bianchi’s cycle racing department was in Piazza Ascoli, and comprised just a small workshop, on the right being a simple workbench, and in the middle, two chains with hooks hung from the ceiling to keep the bicycles suspended while working.

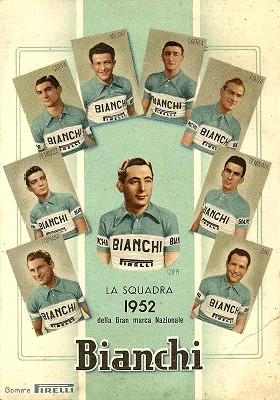

The 1952 Bianchi team

with Coppi in the centre

To re-establish its position in cycle racing after the war, Bianchi sponsored Fausto Coppi, who won the Paris–Roubaix road race in 1950 by a clear 2½ minutes on a bike equipped with the Campagnolo derailleur gear.

Bianchi’s post-war return to motorised vehicles in 1950 focussed on selling economic commuter machines for a transport-starved Italian domestic market, beginning with a basic 125cc Bianchina motor cycle, and that great budget mainstay of those austere times, a roller-drive cyclemotor that Bianchi called the Aquilotto.

A brief spotter’s guide of notes may help identify the different Aquilotto variants:

Initial models had 26-inch wheels, were finished all in black, and a chrome tank with a central wing of cream; then moved to the black chassis with optionally coloured fittings, but retained the chromed tank with cream wing centre; the engine was 45cc, and fitted with a 9mm carburetter. Next came the Aquilotto Sport, with a 12mm carburetter to make it slightly faster. Later ones were fitted with a different style of tank from the first version, which could be either two-tone finished or chrome plated. From 1954 came the Oropa models, where the displacement remained at 45cc, but with a two-speed gear and chain final drive; the Azalea model, also 45cc with roller transmission and a curved top-tube; and the Rapallo model with smaller and lighter frame without seat stays, 24-inch wheels, and engine size increased to 48cc (47.8cc). Next came the Amalfi, where the wheels return to 26-inch and the engine is 48cc (47.8cc). Rapallo and Amalfi models have no clutch; Oropa models have a clutch.

The Amalfi and Oropa models shared the same larger style of frame. The final Aquilotto version, sometimes called the Avanti, was a small-wheel folding moped. And further, the Bianchi Aquilmotor was the roller-drive engine unit that could be bolted to a pedal cycle.

OK, it looks as if we have three little Rapallo Eaglets in the nest then, and in case you might be wondering, Aquilotto is Italian for Eaglet…

Bianchi Aquilotto 179078

As of the last (April 2018) edition, we knew the Eaglets were coming, but didn’t know quite when they might be landing, or what condition they might be in when they finally arrived. This presentation was always going to be something of a gamble, but a gamble worth taking because Aquilottos weren’t formally imported to the UK, so represent quite an infrequent cyclemotor over here. With three bikes arriving together, there shouldn’t be any problem getting a runner to test, except that we didn’t get access to them until June, time was already running out to the editorial deadline, and we hadn’t even started the article yet.

The cycle frames appear quite small, so we break out the tape to measure just 64 inches from beak to tail … only 5' 4", that’s quite compact …

Aquilotto engine engagement

All three bikes are appointed with centre stands and wire rear carriers as standard.

Our first bike is frame number 179078 and matching engine number 48☆179078☆. This obviously original machine, however, looks a little too derelict with flat tyres, broken throttle and rear brake cables, so there seems little chance of actually getting this machine going in the very limited time we have available. It also has no engine or carburettor covers, though does at least give us a ready access to photograph the motor. The shape of the crankcase cover tells us straightaway that the motor is a simple overhung crank design with cast iron cylinder and alloy head.

Location of the engine is most unusual for a roller-drive cyclemotor, we can’t readily think of many other comparable units that mount halfway up the saddle stem? Maybe the Alpino cyclemotor?

The engine swings forwards out of engagement, and backwards onto the tyre on pivots and links from lugs beneath the ‘mixte’ style top frame tubes, to forward and rear of the saddle stem tube. The operation of this is from a chrome lever on the left hand side, which pulls up to latch on top of a round chrome ‘button’ for disengage, then lift and pull the lever out slightly, push down and past the button to relocate underneath for engage. This gives a neat change, with no springs involved, which can be easily operated from the saddle and can effectively function as a clutch if required.

Apart from a visual inspection, there’s little more we can do with this first bike, so moving along to our second machine…

Bianchi Aquilotto TF201928

Our nicest looking second example has black frame with the same slim and curvaceous red tank sexily finished in sweeping lines across a lower chrome section. Frame number is marked at the top of the saddle stem, ☆TF201928☆1F, and matching engine number 201928. This machine looks well appointed, with a cylindrical toolbox clamped onto the stem below the saddle, electric horn, and both right-hand covers present over the engine and carburetter, so there’s actually little to see of the motor from that side.

Wheels & tyres on this one are marked 1¾ × 19¾ on the rear, and 24 × 1¾ / 600 × 45 on the front.

The rims are laced onto half-width hub brakes, which look to be a fairly generous size, maybe 100mm diameter, so we figure the Aquilotto might find these useful for pulling out of a high-speed dive.

The Bianchi logo appears liberally on parts all over the bike: in the centre of the handlebars, on the grips, embossed in the back of the levers, the petrol cap, with ‘B’ headed nuts, stamped into the girder fork links, in the pedal rubbers, on and on … this can be a long game …

The girder forks have pressed steel blades, while the rear frame is rigid.

Front and rear lamps are CEV, switchgear is CEV, and the spun aluminium magneto cover has ‘Bianchi Milano’ pressed in its face, so do you think it might be their own magneto set? We don’t reckon, so let’s have a look, prise off the clip, and inside the magneto set is a CEV Modello 6029.

Sitting aboard, the nicely curved handlebars are low, and set forward of the stem, which feels quite a purposeful and sporty riding position, and rather unusual for a cyclemotor? The engine however doesn’t seem to be a particularly sporty design, of 47.8cc, with its overhung crankshaft to the right, having the drive roller disposed in the middle, and magneto set to the left. The tap turns on below right on the fuel tank; there’s an additional flood-button option on the Dell’orto T1-12-DA carburetter with the usual confusing choke control marked Avv.to→ / ←Marcia which we never fully understand, but interpret as Marcia = ‘confine’, so presume this is the choke position? Press the flood button, try the choke in any position, its all guesswork, and then maybe fiddle with the shutter lever until you find a happy position to run.

Bianchi Aquilotto TF201928

We’re told this number two bike does run, so engage the engine, pull in the decompresser lever under the left handlebar grip, pedal down the road, drop the decompresser lever and keep pedalling. Up and down, but just pops and coughs, so change the choke position and try again, up and down, but just more pops and coughs, but no real indication that our Eaglet is ready to fly.

We decide to check it out, clean the carburetter, change to fresh fuel, clean the plug and check the spark, and then give our bird another chance to fledge. This time we opt for the lower effort method of pedalling on the stand, and the motor bursts into life, so we disengage the drive and run the motor a little to warm.

The tin-cylinder exhaust seems to noisily leak smoke from the ineffective joints that typically plague these economy screw-together systems. While the motor sounds as if it might be more ready to rev, it behaves as if it’s running rich, and still doesn’t feel strong or responsive enough. Trying different choke positions doesn’t really find any happy medium, and after a little while it seems like time to try and give it another go, so we nudge off the stand and pedal away to gain a little momentum before feeding in the drive. The engine just splutters out, and no amount of pedalling effort achieves any more than the occasional cough.

We leave Chris making efforts to get it to go, but to little better result, until the final decision that it feels to be running rich, and won’t pull under load—so there’s something wrong, which seems pretty conclusive.

Bianchi Aquilotto 186533

Meanwhile we’ve moved on to assess our third Aquilotto. This bike is finished differently, with a plain red tank and dark olive green cycle frame, but all obviously the original paint. Its frame number is 186533, and engine 183823, but appears a little derelict with flat tyres, rusty chain, and a dry tank with no tap or fuel line.

Two Eaglets down, and we now need to get one to go or we won’t get a road test!

We set to work, with James pumping up the tyres and oiling the chain, while I check through the carburetter and sort out a tap with some pipe. After a short time we can remove the plug, then spin the motor over—and yes it sparks, so there’s still a hope…

We fuel up, to pedal it up on the stand, and … Ahhh? … Where’s the decompresser lever? It’s supposed to be below the left handlebar. There’s just the valve in the head with no operating mechanism, and looking underneath the handlebar reveals that the lever bracket has been sawn off the handlebar! How smart is that? OK, revised starting procedure required because it’s going to be rather difficult to start on the stand without a decompresser, so we’ll have to pedal it up the road to get a bit of momentum, and then bang it into drive. Fortunately the motor fires up right away, so it goes, but sounds very noisy as this tin exhaust also leaks and smokes from every joint. We disengage the drive to free-rev the motor a little and blow the cobwebs out, and it soon seems to settle to more regular firing as it warms up, so we pedal away, and re-engage the drive. This bike initially manages to pull under its own steam, but quickly weakens, and subsequently struggles to return the 300-yards back to the workshop without pedal assistance.

Suspecting weak compression, we pop off the magneto cover to spin the flywheel, and fail to even feel the compression point at all.

Bianchi Aquilotto 186533

Chris gambles his diagnosis on stuck piston rings, but we think maybe head gasket? We now desperately need one bike to go, so take off the cylinder head (it’s only four nuts), and there it is, a well-blown head gasket! Chuck that away, a little clean up, and then seal the joint with high temperature RTV silicone.

Considering the age of these motors, we were wondering if they might be a deflector top design, but found an alloy flat-topped piston with Schnurle loop scavenging in the iron cylinder through two conventionally placed side transfer ports, though the alloy head does look to be fairly low compression with a large hemispherical combustion chamber which we’d guess around 6:1 ratio.

Leaving the joint to cure overnight, we return in the morning for the moment of truth. Start her up, then a short run down the lane and back tells us we seem to be good to go, so James flies as wing-man to pace the run as we have no speedo. Considering how little pre-running our third Eaglet has done, the motor seems very settled and quite docile at low revs with little snatch, but begs a little pedalling assistance to pick up initial speed; an expected effect of the obviously low compression ratio.

Throttling on (with the exhaust noisily blowing from all its joints again), we readily pick up to a contented cruising speed around 20mph. The riding position feels quite comfortable considering the small stature of the frame, and the low-forward handlebar position means the rider naturally assumes a sporty stance, which feels rather unusual for a cyclemotor.

The bars convey an impression of firmer control than the usual sit-up-and-beg position of a North Road bar-set, so it’s very easy to settle quickly into the riding position of our Rapallo Aquilotto. Turning onto the straight with our motor up to temperature, we decide to try for our first fast run, but this is blighted by a top-end misfire along the whole mile, which still hasn’t cleared by the time we get to the end.

Bianchi Orsetto

Backing off the throttle and disengaging the drive lever to turn in the road for the return run, we try one last trick and briefly rev the engine off drive until the misfire seems to clear, pedal up to speed then re-engage drive, throttle-up, and go for broke. James peels in behind to clock the pace, as we tuck down and hope for the best.

This time the motor runs clear right up its range, so we nestle in tight and low to wring the absolute best we can from our mount as we roar back down the one-mile straight. This time our efforts are encouraged as we seem to hear the revs creeping slightly higher, until the exhaust note peaks out in a flat drone as we thunder the final stretch at a paced 26mph.

Great, that’s all we needed, just a decent test result from one bike will do, and our gamble paid off. We’re happy that we got everything we could out of the motor along the on-flat return run, and its low compression ratio certainly wasn’t capable of pulling any more pace.

The brakes proved generally capable, despite the front drum creaking at any application. The sprung pressed-blade girder forks took out some road feedback, which was about as much as you might hope for in the early 1950s, and was probably presumed at that time to be an improvement upon the hammering you’d get from a rigid fork.

And in all the excitement, we just plain forgot to even try the electrics.

1962 Autobianchi Berlina

Into the early 1950s Bianchi’s basic production Aquilotto and Bianchina 125 were joined by a further 175cc two-stroke motor cycle. The four-stroke Bianchi Tonale 69mph roadster was introduced in 1954, an impressive 175cc chain driven overhead camshaft single-cylinder sports bike designed by Sandro Colombo, that was also developed into a racer and was joined by a 220cc 100mph competition version, plus 175cc and 200cc motocross models.

Bianchi subsequently took on Lino Tonti as its research engineer in 1959, to produce a new range of 250 and 350cc DOHC twins to compete in the motor cycle Grand Prix series of 1960, along with a few over-bored 498cc works versions for the 500 cc class races.

After a number of racing and competition successes, the racing team was dissolved in 1965.

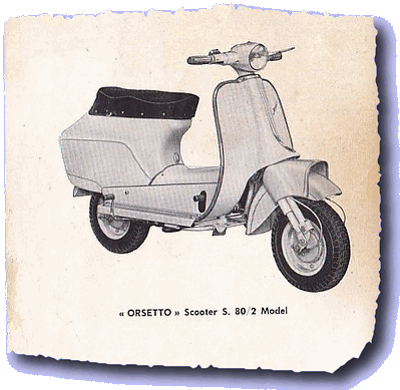

The company continued its production motor cycles with a further 350cc model for the Italian Army, and the Orsetto 80 civilian scooter, which was also licensed by Raleigh to sell in the UK as the Roma scooter. Bianchi produced motor cycles up to 1967, when it sold out the motor cycle production license to Piaggio, but retained its bicycle manufacture, and remarkably continued producing Aquilotto models until 1969, when Autobianchi car division was sold to Fiat, leaving Bianchi to concentrate only producing pedal cycles.

Since May 1997, the remaining Bianchi Cycles Company has been part of Cycleurope Group, which is owned by the Swedish company Grimaldi Industri AB.

In July 2017, Bianchi and Ferrari announced a partnership to develop and produce a new range of ‘high-end’ branded cycle models.

FIV Edoardo Bianchi SpA is now famously known as the world’s oldest bicycle manufacturing company that is still in existence.