Our original Fifty Quid feature kicked off with a trip down memory lane, harking back to the ‘good old days’ of the 1970s when you used to be able to pick up old mopeds for next to nothing, and the question was: what might you be able to get within £50 today?

With old mopeds lately becoming retro-collectibles, it might not seem so easy to do that anymore, but the Mopedland and Moped Doctor workshops readily demonstrated a number of Fifty Quid examples—provided someone was prepared to do a bit (or more usually a lot) of work.

The original Fifty Quid article certainly generated quite a bit of enthusiastic feedback from our readers, who seemed captivated and inspired by the concept of almost zero budget re-cycling—so could the workshops do it again?

Of course they could, and surprisingly easily as it happened. The Mopedland workshops quickly produced twice as many interesting micro-budget machines as we could get into our second Fifty Quid–2 article, so several of these bikes are being carried over into other features.

It must be said that the three examples selected for our feature were either totally disassembled basket cases with missing parts, or utterly ruinous wrecks. All generated much the same comment from visitors to the workshops: ‘You’re surely never going to make a bike out of that again, that’s just scrap!’ … that’s how bad they were!

These machines all arrived in extremely distressed condition, which is exactly why they came in for less than £50.

Starting with our oldest bike first, this is one of the great classic mopeds: a Raleigh RM6 Runabout.

We don’t like to think of any Runabout going for scrap just because it’s in pieces, because it’s now nearly 50 years since Raleigh built the last of these models, and any that have lasted this long must surely deserve to survive by now?

This bike was bought-in by the workshops, completely dismantled, along with a sizeable quantity of unrelated spares for £80 the lot. Since the parts were valued as much as the disassembled remains of the bike, it’s probably fair to say the bike came in at £40, which qualifies for our feature.

What a mess! A total jumbled basket case, missing carburettor and number plates, but it did have an accompanying V5c document that correctly identified the frame number, so at least there was a registration number with it.

The frame had been completely stripped by the previous owner, with some parts left in primer, and that’s as far as its restoration had got in fifteen years.

The engine required a complete strip and rebuild with new main bearings and crank seals.

Cycle parts were repainted back to white & green colours as they appeared in the registration document.

Wheel hubs serviced, tank cleaned out, lots of component repairs, replacement carburetter … basically a complete reconstruction, but costs kept to a minimum because it was a commercial project. While the bike took a lot of work, paint and parts barely came to £39, and though it might require a new pair of tyres for MoT, that still represents a pretty economical project.

Raleigh launched the RM6 Runabout at the Blackpool Winter Gardens Show, which was officially opened by pop singer Craig Douglas at 11am on 15th May 1963. Power and Pedal magazine subsequently described the Runabout as ‘Probably the most practical, the simplest, and even the prettiest utility moped ever to appear in Britain’. The public unanimously agreed, and bought the bike on a staggering scale. Colour scheme of the first models was described as pearl grey & green (pearl grey actually being a cream or off-white), and our bike dates from 1963, so was one of the original machines.

Many early bikes were cursed with internal HT Novi ignition sets, which in later years tend to develop a complaint of cutting out when they get hot, but our bike already displays an internal low-tension generator with external HT coil, so it’s certainly been converted somewhere along the way.

It’s also clearly no longer equipped with its original engine, because the engine serial number has changed from the registration document. This replacement motor is otherwise the same specification, with continuous-fin cylinder and 6.5:1 compression head for 1.4bhp, so it’s not going to be a rocket ship.

Employing the standard and simple starting procedure, fuel tap turns down for on, 9 o’clock for reserve, at the bottom right of the tank. Decompress with a forward twist of the Amal throttle grip, thumb on the choke trigger under the left-hand brake lever, spin the motor, twist the throttle back … and she burbles into life first time! Runabouts do often show nice easy starting provided they’re set up properly.

Power up the road from a standing start … OK, that was a slight exaggeration. There’s a bit of revving and rattling as the clutch pads scrabble at the drum, then the drive shoes lock in and the motor labours away as it tries to build up momentum. The single-speed drive ratio is hard work for these low power motors at the bottom end of the rev scale, so they will appreciate a little pedal assistance. Fine for an assisted take-off on the straight, but if you try pedal assisting from a junction, then you have to watch out for grounding a pedal or it could have you off.

Along the flat in still air we only manage 22mph before combustion breaks down into bluster of four-stroking due to either the small exhaust port or over-rich fuelling. There seems no way through the condition even when we get the motor hot, which is particularly irritating. The four-stroking only abates under the load of an uphill climb, when firing clears to pull normal two-stroke running and we steadily ascend the slope at 18mph.

Aided by gravity, a downhill run overcomes the four-stroking barrier and our pacer clocks us off at a best of 28mph.

We decide to give the Runabout another chance, returning to base to see if we can find a smaller main jet. The correctly fitted standard jet for its Gurtner BA10 is 20.5, but we fail to find any smaller jets in the stores, so instead, there’s Plan-B … out with the engine and resize the exhaust port!

The original exhaust port is dimensioned 20mm×7mm high, but the later split-fin cylinder re-sized the exhaust port up to 20mm×9mm, so we just raise the port to the later spec. By skimming the face of the cylinder head and removing the 0.63mm head gasket, the compression ratio is raised to 7.5:1 (same as the later split-fin motor), so within four hours it’s all back together and we’ve basically up-rated the motor to 1.7bhp spec, so let’s see how she goes now.

Starting is just the same: pull away seems a little stronger, but this time the four-stoking problem is completely eliminated!

Now we can achieve around 25mph in an upright stance on the flat, but it’s a blustery day and the Runabout is still quite susceptible to being blown down by a strong headwind. It’s now quite easy to build up to 28mph on the flat by catching a bit of tailwind or adopting a crouch, and the downhill re-run now clocks off by our pacer at 31mph. The same uphill climb is now taken at 20mph, so there’s quite an all-round improvement that has cost nothing to do and required no parts.

Lights are switched by an almost hidden toggle underneath the headlamp, with just a basic 15W single filament front bulb and 3W taillight, and seem to work OK. Mounted in the middle of the handlebars from a bracket fixed by the stem bolt, the Miller electric horn was offered as an accessory kit extra for the early RM6 Runabouts, and simply connected with a wire across to the Miller horn button on the left-hand bar. Early Runabouts would have been supplied with an economy bulb hooter as standard, and only when the Royal Carmine Red Super De Luxe RM6 came along in July 1965 did the electric horn start to become fitted as standard equipment.

With calliper front brake, unsprung fork, and rigid frame, the RM6 was the cheapest and most basic Runabout model, but sold very well and achieved huge popularity. It became Raleigh’s last model when the motorised range finally de-listed in February 1971.

Our second Fifty-Quider is a KTM Hobby with Sachs 502/1A engine and, since we’ve never covered this manufacturer in an article before, there’s a bit of a story to tell…

In 1934, engineer Johann Hans Trunkenpolz established a metalworking and locksmiths business at Mattighofen in Austria, the shop becoming known as Kraftfahzeug Trunkenpolz Mattinghofen, though the name was unregistered at this time. In 1937 he started selling DKW motor cycles, then Opel cars in 1938.

During World War 2, his wife maintained the business, which mainly involved diesel engine works, but demand fell sharply after the war, and Johann decided he would produce his own motor cycle.

The first R100 motor cycle prototype was completed in 1951 with a home-built frame, and fitted with a proprietary Rotax/Fichtel & Sachs engine.

In 1953 the business was joined by Ernst Kronreif as a significant shareholder in the new company, which was renamed and formally registered as Kronreif & Trunkenpolz Mattinghofen.

KTM started serialised production of its R100 model in 1954, with just 20 employees, and building motor cycles at the rate of three per day. Later the same year, the company won its first competition title at the 1954 Austrian 125 National Championship, and thereafter continued to use sports competition and racing as a testing and development ground for its production technology.

A new ‘Tourist 125’ model motor cycle was introduced in 1955, and Egon Dornauer secured a gold medal at KTM’s first appearance in the International Six Days Trials Enduro event of 1956.

KTM presented its first ‘Mirabell’ scooter, a ‘Trophy 125’ sports motor cycle, and its first ‘Mecky’ moped in 1957.

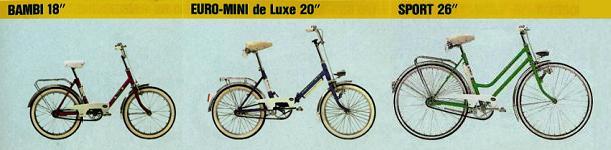

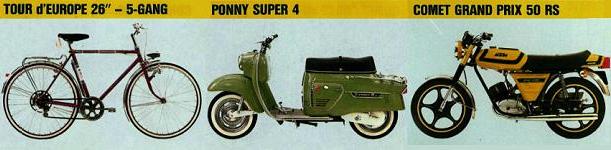

KTM began production of bicycles in 1960, followed by further scooters: the ‘Ponny-I’ in 1960, and ‘Ponny-II’ in 1962.

UK imports of Ponny 50cc scooters began in July 1961 through Cabin Scooter (Assemblies) Ltd, 11 Wharf Road, London W2, and continued up to 1964.

A factory team was established for competition in International Six Day Events in 1964.

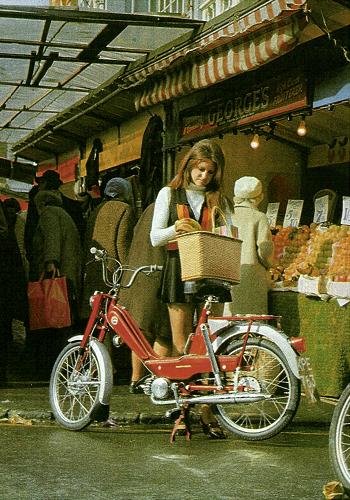

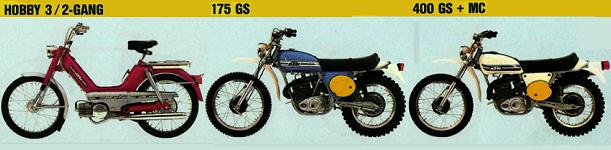

KTM presented the automatic Hobby moped in 1968, which was released in different versions: the original 50cc ‘Mofa 25’ was introduced with a rigid fork and rigid frame, then joined by other model combinations with telescopic fork & rigid frame, or telescopic fork & swing-arm rear suspension frame.

A Mofa 25 could be ridden without the need for any driving licence, but was restricted to a top speed of 25km/h (15.6mph). The engine was the Fichtel & Sachs type 502/1A motor of the usual Sachs 38mm bore × 42mmstroke specification for 47cc, and was simply limited in performance by fitting a small-bore 8mm Bing carburettor.

An unrestricted automatic ‘Moped 40km/h’ (25mph) version also was offered with a larger 12mm Bing carburettor and rated at 2bhp, but was classified under different regulations and needed a driving licence. It was a logical progression that KTM might utilise a moped engine from fellow Austrian manufacturer Puch in place of the German Sachs motor and, in 1970, a Hobby-II model was unveiled, now fitted with an automatic Maxi E50 motor rated at 2.2bhp. This ran in production alongside the original Sachs-powered Hobby, though the Puch powered model never made its way to Britain.

KTM’s expansion had now brought it to the point of offering a range of over 40 models and employing a workforce of 400 personnel.

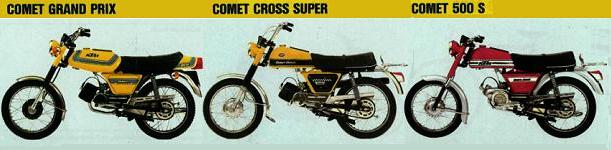

Glass’s Index records that KTM imports to the UK resumed in April 1972 with the base model Automatic Hobby rigid frame moped, then joined by the four-speed Comet Cross sports moped from May 1973, and the Comet GT four-speed sports moped from July 1973.

Listed imports of the rigid frame Hobby ceased in November 1973, when it seemingly became replaced by the De Luxe Automatic Hobby with rear suspension, however our K-registered Hobby Automatic De Luxe was UK registered in July 1972, so we’re not so sure of the accuracy of the official Glass’s dating information in this case—it appears that the De Luxe sprung frame model had actually been introduced earlier.

To a casual glance the KTM might appear fairly similar to its fellow Austrian manufacturer’s Puch Maxi; however the Hobby is a very different animal.

A continental-style, cast-aluminium lifting handle is attached to the front of the seat post. Fold out and lift one-handed by this and the bike is in balance—though it certainly doesn’t make it any lighter!

The wheels are fitted with 2.00×17 tyres on alloy rims and, despite the Sachs 502/1A ‘compact’ engine, the bike appears to be quite a heavyweight machine, so we roll it onto the scales, and 7st 4lb (46kg)—which seems pretty heavy for a simple automatic moped!

One puzzle is when Sachs went to all the trouble to produce the 502/1A ‘compact’ engine, why they also didn’t go for lightness and make the cylinder barrel out of lightweight alloy instead of heavyweight cast iron? It just didn’t figure.

You may also wonder what might be so special about a ‘compact’ engine? Well, the trick is that the motor bottom-end is no bigger than the crankshaft! The crankcase is just a round cylinder with the top-end bolted onto one end, and doesn’t have any of the additional length of conventional motors that house primary reduction drives or a gearbox. The motor still requires a primary reduction drive, so how did Sachs get around that? Well actually, they didn’t—it just looks like they did!

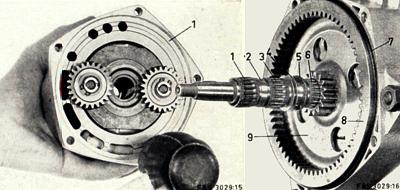

This is the moment you need to get your head around the engineering of what may be one of the most extraordinary automatic moped engines ever made—it’s got an epicyclic primary reduction gear set!

After the crankshaft, in line to the left of the motor, there’s the engagement clutch to start the engine, the centrifugal automatic clutch, then a planetary gear set within a thickness of just 10mm, driving out to the front sprocket, beyond which is the Bosch magneto-set. It’s a fantastically engineered little motor, and all credit to Sachs for pulling off what nobody seems to have before or since, but most of its riders would be completely oblivious of the trickery going on inside—all they want is reliability and performance, and that’s where some of the shortcomings start to creep in…

The motor is built with an overhung crank, which dramatically limits its practical revs because the design becomes prone to vibration. The inboard engagement clutch is operated by the same cable that effects the decompresser, but if you might need to replace the cable—then you have to take the motor out of the frame and strip the whole thing right back to the crankcase to engage the cable in the operating arm, unless you have the impossible skills of a keyhole micro-surgeon to do it through a tiny screw plug hole in the top of the case. For any normal human mortal—it’s simply impossible!

There’s other weird stuff about the motor too…

Even though there’s a decompresser site in the cylinder head, Sachs left that blank! Instead they put the decompresser into the sidewall of the cylinder and vented it through a hole 20mm down from the top of the bore! Why? (… more on this later.)

The Compact engine certainly looks fantastically imagined with its single-sided appearance and radial finned top-end that reflects the impression of a Flash Gordon rocket, but we’re not so sure the reality of its performance might live up to the expectation—because we really do know better (see production notes).

An unusual fitting is the ZKW 60km speedometer—we don’t see many of this make fitted to mopeds in the UK.

The wheels are laced to Sachs pressed-steel full width hubs. The rear hub contains a back-pedal brake effected by the pedal chain, which works a Bendix inside the hub, to operate a conventional brake shoe arrangement by a gear driven cam. Unlike the inadequate ‘coaster hub’ brakes fitted to some mopeds (Phillips Motorised Cycle, Panda Mark 1 & 2), these types of hub generally work quite effectively, and similar hub types were fitted to some Excelsior and Hercules Her-Cu-Motor mopeds.

Swinging arm rear suspension and telescopic front forks are all greased spring units with no damping.

A 6V Bosch magneto set powers the electrics with 15/15W beam–dip headlamp, 3W rear, and an electric horn, while a sprung parcel clip snaps down on the rear carrier … all the luxury fittings of the time.

There are several reasons why operating the Hobby feels as if it’s going to be a little strange … if you rotate the pedals forward, the bike freely pedals forward just like a bicycle without any engagement of the engine, then if you turn the pedals backward it engages the back pedal brake. Because of the hub brake type however, if you reverse the bike, the pedals don’t rotate round backwards like any conventional freewheel sprocket cycle, because the pedal freewheel sprocket doesn’t react like a conventional freewheel. Hobby is much easier to navigate backwards because reversing pedal rotation can be a nuisance when backing many cycles.

To engage the engine, there’s a large lever on the left handlebar, which is orientated so that it looks like a brake lever—but this actually functions as a dual-operation decompresser and starter clutch lock, in much the same manner as on a Puch Maxi. Pulling in the lever engages the motor and opens the decompresser, while turning the pedals makes it spin, then release the lever to hopefully get it to start.

Below the right-hand side panel, the petrol tap is operated by turning what looks like an old style radio knob. There’s a raised tooth on the notches of the knob which vaguely points to some barely visible markings on the panel, up for off, click round to 90° forward for on, click round to 90° backward for reserve, and the knob also clicks right round the full circle, but we don’t know what the 6 o’clock position might be?

The Bing carburetter has a short rod out the top, which you can push down to engage the choke shutter, and a flood button to the float chamber (just like a Puch Maxi) which you can tickle for extra enrichment when it’s really cold. Since it’s a pleasant spring day we resist any urge to agitate the button.

Put it on the stand and kick the pedal forward while holding the decompresser, then release the lever halfway down its stroke … and the motor starts first time. Impressive! The engine sounds really good with a deep thumping tick-over, as pulses of smoke burst from the exhaust and rise around us in the still afternoon air.

We gingerly open the throttle to feel if the choke will clear, which it does quite readily, and with a couple of blips to clear the tubes, it looks as if the bike is up and ready to go!

The engine certainly feels crisp and responsive on the throttle. Nudge off the stand, wind back the twistgrip, and the deep tick-over beat from the silencer clears to a flat drone as the motor comes under load, then the automatic clutch feeds in for a strong torquey pull away on low revs.

Hobby gives all the impression of an old-school moped, sounding and feeling really strong!

The speedometer needle swings round the clock as we accelerate quickly up to an indicated 40km/h, then the combustion breaks into bout of loud staccato four-stroking as cylinder gas transfer gets all in a tizzy due to inadequate exhaust porting—and that’s obviously how it’s going to be from now on…

Along the flat, the motor mostly runs along at a noisy four-stroke firing gargle, periodically interrupted by phases where combustion occasionally clears back to normal two-stroke running as the bike comes under load against any slight incline or forward wind. We find it’s also possible to clear the four-stroke firing by backing off the throttle to drop speed a little, then open up again so the motor comes under load—but the respite is only temporary, the misfiring returns as soon as the revs catch up again.

We rather hope that it might improve a little when the engine gets hot, and it does to some degree as heat works into the motor, so by the time we get onto the main road we can work the speedometer up to indicating 50km/h—but the wavering needle isn’t accurate. Exchanges with our pace vehicle reveal our speedometer is 10km/h optimistic, so Hobby’s best on flat performance achieved only 26mph, which was mostly in four-stroke firing. Ducking into a crouch would barely make any difference since the bike was more held back by its disrupted combustion than by air resistance.

The racket that Hobby creates from its exhaust while running on throttle makes it like riding a mobile anti-aircraft battery! People are certainly going to look up to see what’s causing the din!

Our best downhill run in a crouch was paced at 29mph, at which you could feel vibrations coming in from the overhung crank design exceeding its expected rev range. The four-stroke firing had practically given way to even more infrequent six-stroke firing at this speed, and there would be little point in trying to extend the motor’s rev range by enlarging the exhaust port since the overhung crank would only be running beyond its comfort zone, and stress the engine to a premature failure.

The Sachs 502/1A engine has a contained operating rev range because of its design, and will only work within that envelope. It really wouldn’t be sensible to try and make it do any more than it does in standard trim.

The motor however seems to relish the challenge of any uphill climb. As the gradient changes, the four-stroking suddenly clears to clean two-stroke running and the engine digs in hard to power up any ascent. Level out at the top, and combustion disrupts back into the wretched four-stroke firing again as the motor comes off load.

Uphill climb paced at 24mph cresting the rise, so speed had barely dropped from the bike’s flat running pace.

Lights seemed pretty good considering Hobby only has a 6V × 15W AC headlight and 3W tail. Both brakes displayed effective performance, however the rear seemed to require a long arc of back-pedal rotation before it would engage, which made its operation point particularly difficult to judge, and the brake could readily come in hard when it did bite, so the rider needed to be careful.

Another trap the unfamiliar rider can easily fall into is instinctively grabbing the decompresser lever in mistake for a brake, which doesn’t quite achieve the desired stopping result.

It may seem slightly unusual for a bike equipped with a decompresser to also be fitted with a cut-out button to kill the ignition (early pedal versions of the Puch Maxi had the same arrangement). Most machines started on a decompresser are invariably also stopped on the decompresser, but using the decompresser lever on Hobby also engages the clutch, so if the bike is standing on its wheels, it clumsily lurches forward to stop in a stall (not cool).

Push the cut-out button and the engine just quietly dies out (much cooler).

If however you happen to have put the bike onto the stand while the motor is still ticking over, and then pull in the decompresser lever, it doesn’t stop! The rear wheel starts spinning because the starter clutch also becomes engaged, and pulses of two-stroke smoke loudly vent from the decompresser—but the engine continues running (very silly!)

This seems to happen because the decompresser only partially decompresses because it ports through the sidewall of the cylinder, so there’s still enough compression for the engine to continue running with the valve engaged.

What’s even stranger is that the cylinder head has a blank site for a decompresser valve to be fitted, so it’s something of a puzzle why Sachs configured the motor in the manner they did?

A Hobby-III appeared in 1974, with a deeper step-through frame, larger tyres, a large carrier, indicators, and lots of flashy chrome plating. There was also a version fitted with a Puch two-speed, hand-change engine.

1977 brought the Hobby-L, a new two-seater model with cast magnesium alloy wheels and carrier with suitcase pannier mountings.

Ernst Kronreif died in 1980. Two years later in 1982 Johann Trunkenpolz also died of a heart attack, so his son Erich Trunkenpolz took charge of the company’s management and its name was changed back to Kraftfahrzeug Trunkenpolz Mattinghofen. By that time, KTM had contracted back to about 180 employees and a turnover of €3.5m, but without the guiding hands of its founders at the helm, scooter and moped turnover sank rapidly, business confidence in the company faltered, and production temporarily halted while the organisation was restructured.

In 1988, a US subsidiary KTM North America Inc. was founded in Lorain, Ohio, as international business then amounted to 72% of the company turnover. Erich Trunkenpolz died in 1989 and, in 1990, the now foundering and leaderless company was renamed KTM Motorfahrzeugbau AG. In 1991 KTM applied for insolvency, and its management was subsequently taken up by banks, who split the company into four new entities in 1992: KTM Sportmotorcycle GmbH, motor cycles division; KTM Fahrrad GmbH, bicycles division; KTM Kühler GmbH, radiators division; and KTM Werkzeugbau GmbH, tooling division. KTM Sportmotorcycle GmbH started operation in 1992 and later took over the sibling tooling division KTM Werkzeugbau.

In 1994 KTM Sportmotorcycle GmbH was renamed KTM–Sportmotorcycle AG, and in the same year started production of a new ‘Duke’ series of road motor cycles. In 1995 KTM acquired Swedish motor cycle maker Husaberg AB, and took control of the Dutch company White Power Suspension. KTM continues as a successful manufacturer of modern sports and Supermoto motor cycles, but no longer makes mopeds.

Our third and final Fifty Quid–2 feature bike is a Piaggio Boxer 2.

Engine number E1M 72194 and frame number BTM1T*302627* dates the bike to early 1973, and among the very first batch of Boxer 2 models imported by Douglas.

The original Boxer model became imported to the UK from March 1971, and seemed to be pretty much the same bike in a single-seat version, and without rear footrests. Imports of the single-seat Boxer concluded in February 1973, when it seemed to have been succeeded by the Boxer 2, which simply appears to be a two-seater variant of the same model.

During renovation, the workshops ‘observed’ the motor was fitted with a Dell’orto SHA 12/10, which has an ‘underwhelming’ 10mm intake venturi, and consequently predicted as ‘not to be expected to deliver much in the way of performance’.

Also the Boxer V-belt primary transmission comprised just a simple single-speed clutch on the front drive pulley (unlike the Si, which featured a CVT), so the Boxer motor doesn’t look as if it’s expected to develop much power, and the transmission isn’t expected to make much of what the engine produces—all the signs are there’s going to be a slow theme going on with this bike.

Retrieving the original specifications for Boxer 2, the stats tell us the motor was blessed with a 9:1 compression ratio, 38.4mm bore × 43mm stroke, rated at 1.4bhp and listed 40kph (25mph) … Yes, that’s pretty slow for a moped being sold on the British market in 1973.

There are certainly some service difficulties with these early Piaggio motors. Everything is fine when they’re working, but the magneto set features conventional contact point ignition, which is naturally going to require a service from time-to-time, and the only way to access the magneto is: you have to take off the exhaust and carburettor, disconnect the decompresser cable, remove the transmission, and take the engine out!

It’s easy to imagine that the scale of that operation might defeat a few owners, so when many of these Piaggio models break down with ignition related faults, they can stay broken down for a while or become scrapped.

Once you’ve managed to find and release the hidden spring-loaded latch at the back of the saddle, the dual seat hinges up from the front to reveal access to the petrol tank filler cap, surrounded by a small tool tray.

The telescopic forks appear to be oil filled, though they seem to bounce fairly freely on their springs, and don’t feel to be generating much in the way of motion damping action.

The rear suspension is a sort of swing-arm arrangement, where the whole sub frame assembly pivots from the front, and there’s a single heavy-duty captive spring just ahead of the rear wheel. Piaggio called this their Vespa Souspension system—or perhaps they couldn’t spell? Without any obviously visible conventional spring units, you might think the frame could be rigid, but the whole frame appears to be magically floating when you sit aboard, then bounce up and down on the saddle and the bike reacts like a trampoline! The specifications described the rear suspension as having a hydraulic shock-absorber, but we’re not so sure there’s much damping effect any more…

Starting: turn the fuel tap on right-hand side between the trim plate and the side panel. Oddly, the fuel tap rotates in an anti-clockwise direction, 3 o’clock off, turn up to 12 o’clock for on, and back to 9 o’clock for reserve. Click down the choke lever through a small port in the side panel; it will automatically release when the throttle is opened wide.

Pull in the decompresser trigger beneath the left-hand bar, firmly spin the pedals to get the motor turning, drop the decompresser trigger, and if you’re lucky the motor picks up.

Engine running shortly starts to stifle on the choke, so open the throttle wide to release the shutter, then run the motor free a moment to clear the tubes.

Nudge off the centre stand and slide aboard, throttle on, and Boxer pulls away to a smooth drone from its exhaust. Considering the low power rating of the motor, we’re quite surprised how well it does get away from a standstill, and though a little pedal assistance might be appreciated by the motor, it can still accomplish the task single-handed. Building speed along the road involves a little settling into a comfortable position along the saddle, which has a shiny, slippery surface and a mattress sprung frame. There is some bouncing around involved in this operation, which is amplified by the springy rear suspension, and before you know it the whole mobile trampoline can be pogo-ing along in a wild oscillation.

This chassis will certainly soak up the bumps for a soft and gentle ride, but it’s obviously going to be at the comfy armchair end of the sports spectrum for handling on bumpy corners.

We’re reliant on our pace vehicle for performance readings since our Boxer no longer has any speedometer fitted, though originally it would have come equipped with one. Speedometers are not required on any vehicles below 100cc and, let’s face it, there’s not really any expectation that our Boxer is going to blast through the 30mph barrier.

Boxer pulls capably enough up to around 20mph, above which it soon starts to run out of steam as the motor breaks into a splutter of four-stroking from the limited porting. This condition does improve as a bit of heat works into the cold iron cylinder, but will certainly hold the bike back in the early phase.

As engine temperature increases, our pacer clocks the Boxer maintaining around 24–25mph along the flat in still air in upright position, and then sometimes managing to creep up to 26 in a crouch.

By easing back the throttle to clear four-stroking phases, then opening up again in bursts, we managed to tease the downhill run up to 28mph, but that really was the ceiling as gravity assistance and the motor’s four-stroking barrier found a natural balance.

The following uphill climb dropped our pace back to 19mph, where the motor dug-in to a clean two-stroke pull, and slugged doggedly up the incline.

Our pacer reported quite a bit of smoke burning off from the exhaust, despite running only a low 33:1 semi-synthetic mix, so maybe the silencer had some old oil trapped inside?

The throttle, decompresser, and brakes are operated by Domino controls, and while the brakes felt firm on the levers, actual retarding performance proved remarkably ineffective. Considering the unchallenging capability of the bike, this was quite a poor braking report, and probably a good job the bike was fitted with heavy-duty 2.5mm thick inner cable wires, since it’s easy to imagine there could be times when the rider might want to be pulling on those levers pretty hard in the desperate hope of trying to stop.

The electrical set seemed pretty feeble, with the horn barely managing a quiet froggy croak at low revs and a slightly more buzzy effort at higher revs. We don’t know what the actual generator output is, but it did appear to be struggling to drive the rating of the electric horn.

The original headlamp wasn’t present among the dismantled parts when the workshops took this Boxer 2 in, and we don’t know what rating the front lamp was supposed to be. A headlight subsequently was constructed with the aluminium ‘Gatso camera look’, and fitted with 6V × 15W bulb. Put your eyeball on the lens and stare into the 6V × 15W headlamp filament… Is it on? Oh yes, just a dim little glow.

We know the rear lamp bulb was initially over-rated because of difficulty in sourcing the correct 6V × 3W miniature festoon bulbs, so was fitted with a 6V × 5W festoon, which seemed to give a reasonable light at the back—seemingly however at the cost of the headlight.

Re-trying the headlamp with the rear bulb removed demonstrated a reasonably bright light, so the festoon taillight socket was replaced by an MES socket, allowing the fitment of a low-rated 6V × 0.3W cycle bulb—and now both lights appear to work fine.

Sometimes these things are just a matter of experimentation.

For cycling mode, a pedal latch on the rear hub disengages the motor by pressing a button through the back of the left-hand side panel; the latch can be released to restore the drive by tripping a lever on the hub.

Tyres are 2.50×17 rear, and 2.25×17 front, so it looks as if Piaggio might have changed the wheel size for the Boxer 2, since the original Boxer listed 2×18 front and 2.25×18 rear.

The rear carrier is a massive 26-inch-long tubular frame, mounted from its forward point ahead of the rear wheel, with pannier frame supports beneath the pillion saddle, and a rack extending beyond the back of the bike with a spring-loaded parcel clip. Consequently the bike measures 68½ inches nose to tail, so Boxer 2 is quite a lengthy moped.

The centre stand gives firm and steady parking, and seems stout enough to even take a degree of pedalling up on the stand.

A steering lock protrudes forward from the headset, but as usual, the key has long been lost.

Riding Boxer proved rather more pleasant than we expected, and despite the relative lack of performance, rode reliably and reasonably well. It’s easy to imagine them being used as coffee shop scoots around traffic clogged Italian towns. Treated like a powered alternative to the bicycle, performance was practical up to 20mph, which would be adequate transport in a town environment, and the frame was comfortably capable of seating a pillion passenger.

The Boxer would, however, be completely left gasping as soon as it found itself on an open road, but the general experience was OK, and not as dull as we expected. Despite the limited performance, we actually quite liked it…

Imports of Boxer 2 completed in January 1974, so the model only had a sales run of just one year—surviving examples are now most infrequent.