When the first Honda C100 Cub models were presented in the UK on the Scootamatic stand number 83 at the Earls Court Show in November 1960, could anyone have taken seriously the prospect of Japanese motor cycles being sold in Britain?

Scootamatic obviously couldn’t see any appeal in them at the time, and thinking the Honda wouldn’t sell, declined the opportunity to take up a distribution licence—a decision they must have subsequently regretted many times!

It was two more years before Honda models returned to display at Earls Court, and this time unbeholden to the whims of any prospective agents, since the company had now established its own import and distribution as Honda UK. Imports commenced from November 1962 for sales onto the British market in 1963 season.

Closely following Honda’s lead, Suzuki also established its own marketing and distribution as Suzuki (GB) Ltd at 87 Beddington Lane, Croydon, and began imports in October 1963, launching with an initial five model range.

The opening line-up presented was:

M15 Sportsman 50cc @ £95–11s

M12 Supersport 50cc @ £109–4s

M15D Sovereign 50cc with electric start @ £114–9s

K10 Sports 80cc @ £122–17s

And, as flagship, the T10 250cc twin @ £248–17s.

The second Japanese wave had arrived, and for an already faltering British motor cycle industry, this really was the thin end of the wedge.

Back in April 2011, we introduced an article on the Suzuki ‘Sportsman’ 50cc motor cycle … well, now we’re in a position to present a sort of follow-on to that feature with one of its sister machines.

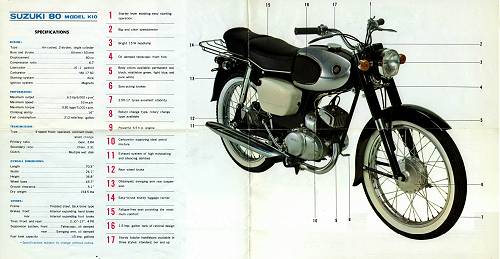

The Suzuki K10 ‘Sports’ 80cc motor cycle was another of the initial five models presented by Suzuki for launching sales into the UK in 1963.

The first question one might ask is why 80cc?

75cc motor cycles are explainable in that the Italians introduced a 75cc road racing category, so that’s why there’s a number of machines found with that capacity, but at 79cc, the K10 is 4cc over the mark for qualification into the Italian road race category, and the Japanese certainly never competed in that particular sport section back in the day, so it’s definitely not that…

Under-100cc capacity (98/99cc autocycles) are generally derived from the French Bicyclette à Moteur Auxilaire (BMA) specification of 1926, which introduced the: under 30kg, less than 30km/h performance, below 100cc capacity, and fitted with pedals, to qualify for exemption from registration … but autocycles were already extinct over five years before Suzuki washed up on our shores, and its modern lightweight motor cycle construction was certainly no reflection of the old BMA spec.

80cc might seem an odd size? Apart from some other Japanese Yamaha models, only the HEC–Levis autocycle comes to mind in that capacity, so we did a bit of digging around … and the actual reasons seem to originate back in Japan.

From the beginning of August 1952, four-strokes up to 90cc and two-strokes up to 60cc were freed from driving test requirements in Japan, which seemed to initiate the promotion of small capacity machines.

In 1960 a Japanese market research study was performed, which indicated there would be significant demand for lightweight bikes between a 50cc moped and 125cc motor cycle, while Japanese home market changes to tax regulations relating to two-wheelers at this time made it apparent that the best advantage could be gained if the upper capacity limit did not exceed 90cc.

Hence, looking at Japanese light machines from the early 1960s, one finds various Honda 90cc scooterettes and light motorcycles, Bridgestone 90s, Yamaha and Suzuki 80s, etc.

The other point worth making, is don’t go thinking that the K10 is simply an M15 Sportsman fitted with a 30cc larger engine—it’s absolutely not! The K10 is a completely different machine.

Admittedly, to a cursory glance it may appear visually similar, but look a little closer and the penny starts to drop.

Hydraulic damped telescopic forks, where the Sportsman only had leading-link. Our ‘80’ has the same 2.50×17 wheel & tyre size, but those brake hubs seem bigger on the K10, and there’s a strut down to the engine from the headstock. Surely the petrol tank’s the same … but no, it’s not! The pressing is different; K10 has a different shape and a styling line below the badge!

The engine is given as 45mm bore × 50mm stroke for 79cc @ 6.7:1 compression.

Weight of the M15 50cc Sportsman motor cycle was listed as 128lb (58kg), but rolling K10 over the scales dials up 155lb (70kg), which is coming practically 2-stone heavier, so these are pretty obviously very different vehicles.

Our machine is an exceptionally original and unrestored example, wearing a dealer badge riveted to the rear lamp bracket which tells us this machine was supplied by Moore’s of Hemel Hempstead, and confirmed by the UR index issued from Hertfordshire Authority in 1964.

Its wheels are still shod with the original Japanese Inoue 2.50×17 tyres! Any replacement rubber wouldn’t have come in this brand, so the low mileage on the odometer appears to be absolutely genuine.

K10’s speedometer set covers the same 80mph range as the M15, and we’re pretty sure this is the same instrument used on both models, though the respective plastic nacelles that carry it are certainly different.

A ‘running-in’ petroil mix is given on an original sticker still on our fuel tank, as 15:1 mix for the first 300km/190 miles. That’d be for old mineral oil lubrication, then after running in, the oil mix can be reduced to 20:1 … no wonder we remember these old ‘Suzies’ as particularly smoky old kippers!

Our Suzy’s four-position ignition switch is located down in the left side panel off–on–on with lights–park, where you can remove the key leaving the side lights on.

Switch on the ignition and a pale yellow warning light in the speedometer dial glows to indicate the gearbox is in neutral, which was pretty much the cutting edge of technological rider aids of the time. We click the gear change rocking pedal into first and watch the light go out, then back to neutral and it comes on again … wow! Still awesome technology! Just like watching re-runs of those original episodes of Star Trek!

Dragging ourselves away from the hypnotic properties of the neutral lamp, we’re then strangely drawn to the absolutely genuine and original Suzuki toy-town indicators that look as if they might have come from a Jamboree bag or Christmas cracker, and don’t so much blink, as seem to slowly glow brighter, then fade dimmer again. The indicator switch on the right hand cluster, left–off–right, proves a little delicate to set in the centre/off position, so tends to go from flashing one way to flashing the other. Once we manage to trick the switch off again, we think we might not bother with that anymore.

The left handlebar cluster has a matching style switch for beam–dip, and horn button below, which struggles to rouse a feeble dying groan, so we figure that’s another aged electrical item that’s giving up the ghost.

There’s a steering lock on the bottom yoke that works from the same key as the ignition. Press down the footbrake pedal and a brake light comes on at the back. All the mod cons, and the engine isn’t even running yet!

All this stuff may seem a little basic and corny today, but you have to consider that our K10 was directly competing for sales against the 75cc Beagle, which was just £95 in 1964. While BSA’s effort hardly offered any of Suzuki’s features, and didn’t even have a battery, the K10 was appreciably better equipped, but did need to be promising something since it was £27–17s more expensive—and that was a significant amount 50 years ago!

Now approaching the point of being ready to take this for a spin, a rotary choke lever tops the left hand lever set, so wind that full-on anticlockwise. Fuel tap under the left tank side is equipped with on-off–reserve plus a gravity filter, and having a seemingly deep centre ridge to the tank with no balancer tube, we figure there would probably remain a fair fuel volume trapped in the right hand valley, so tipping the bike over might find a ‘second reserve’ in case of emergency.

Just feeling the kick over instils a confident feel to the motor, of smooth rotation with a firm compression, then a couple of prods at the starter readily gets the motor warming on the stand.

The exhaust produces a gentle and subdued popping note as we leave it to simmer on the choke while we kit up. The tick-over continues quite expectantly, waiting patiently for us. Within a couple of minutes you’ll be needing to back off the choke as the engine finally warms, or the tick-over will slow and fade out, so dial off the choke and blip the throttle to clear the tubes. The motor generally sounds clean, apart from a small background level of backlash noise from the gear primary drive.

Looking round at our pacers (we have two escorts for this run—see production notes), I guess we’re ready to go?

The cylinder block is a large finned lump of cast iron, so the motor will probably take a while to heat up thoroughly, so we might not be expecting representative performance till later in the run.

Clutch lever action is light; gear selection easily clicks in on the rocking pedal, all forward four-down with neutral at the bottom of the box. The old cursor-slide twistgrip has a typically big twisty handful operation to turn, and invariably lingers in whatever position you leave it set. Feed out the clutch and K10 delivers quite healthy torque from low revs, so there’s little need to buzz the motor away, though it’s completely un-fazed if you do want to do that. The wet multi-plate clutch engages smoothly and controllably, and the acceleration phase maintains this even torque right up through the rev range making general use very easy to manage, and readily clicking up through the gears in a very efficient manner.

The whole feel of the motor is very confident and efficient, so it’s easy to imagine how the new Japanese tide began to make such an impression when it washed across our shores in the early 1960s. The handling doesn’t, however, come across quite so positively. Low speed steering is heavy and cumbersome, almost feeling as if the tyre might be flat. We check the pressure and the head bearings aren’t tight, no, all good there, so we maybe put it down to the fact the bike is still fitted with its original Inoue 2.50×17 tyres to front and rear. The original Japanese market tyres were widely criticised in various period tests, and it’s easy to refresh those memories when you ride them again!

Early Japanese machines were often scathingly reported for sloshy suspension that compromised the handling, but K10’s telescopic forks seemed to work quite well to us, giving a smooth, comfortable and stable ride.

The rear shocks also kept the bike reasonably on track even when we started hustling through some twisty & bumpy sections. The ride was a dramatic improvement over our Sportsman test, where its leading-link front forks and rear springing readily introduced an element of terror at rather lesser speeds through the same sections.

Engine performance of the K10 is strikingly in contrast to later two-stroke tuning, which generally tends to be flatter at lower revs, then peak into a power band as the porting comes on. K10 produces a softer and constant power delivery right up through its range, then tops out on its porting before the runaway rev-screamers of the following decade onward. K10’s revs just seem to tail out earlier, which appears to be its way of saying that it’s time to change up to the next gear.

The 80mph speedometer on our Suzy worked in a manner, but the instrument failed to overcome the resistance of its internal dried lubricant from having stood since 1982 in a cold cellar, so indication only slowly crept up to a best indication of 40mph, and when we stopped, the needle similarly took its own time to slowly settle back down to zero again.

It’s probably not an unfair expectation that it might deserve a service after half a century. There was a lot of negotiated debate between our two pace vehicles as to exactly what K10 officially achieved, until results were finally agreed as 49–50 on flat, 52mph on the downhill run, and dropping back to 40mph in top gear on the following uphill section, which was a most commendable climbing capability for just a little 80!

The Suzuki range was extended from February 1964 by the addition of a K11 model 80cc @ £128–10s. The K10 Sports was joined by imports of another 80cc K10P model from November 1966, which actually turned out to be its succeeding model the following year as the K10 was delisted in September 1967. The K10P was shortly discontinued in September 1968, and the K11P in June 1969, as the last old 80cc motor based machine was replaced by the first model of the new A100 range.