Casalini was a business reportedly founded at Piacenza in 1939, but the initial years of the company seem barely recorded, so little is known of its early history. Several motor cycling encyclopaedia (who only tend to keep repeating one another’s errors), mistakenly suggest the business starting in 1958 as a ‘mini-scooter producer who switched to manufacture of a wide range of mopeds’, or ‘maker of 50cc and 125cc two and three wheelers for carrying goods’. The company first comes onto our radar as a 1952 edition of Moto Revue presented a proprietary frame and fork kit being offered for sale by Italian manufacturer Casalini, which later seemed to turn up in the UK in 1955 as the still-born Sinclair–Goddard Power Pak Mo-ped project, which never made it to production.

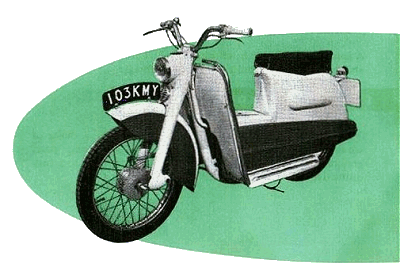

Dunkley S65

The most likely connection between Casalini and Power Pak’s Managing Director, Harold Easton, would seem to be the Italian designer Bruno Fargion, who is reported in press notes as moving on from Sinclair–Goddard to Dunkley at Hounslow, and credited as designer of their two-speed, four-stroke motor series.

It might appear more than co-incidental that Dunkley’s first S65 scooter, announced on 30th January 1958, was also based upon Casalini chassis components, and it has to be concluded that Bruno Fargion must have had some positive connections with Casalini.

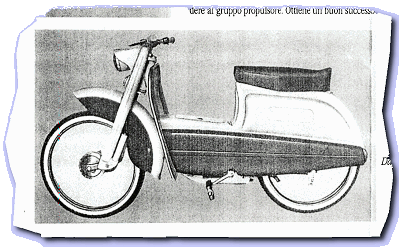

Casalini seems to have produced its own version of this scooter model for sale under its own ‘David’ branding, as well as selling the kit to Swiss manufacturer Ticino who presented a mo-scoot pedal version fitted with a 49cc Italian Demm moped engine in 1958. Another derivative turned up under Dutch branding as the Typhoon David B48 Bromscooter, fitted with a Typhoon Tourist single-cylinder, 48cc, two-stroke, two-speed moped motor.

Whether Casalini was doing the actual sheet forms for these various body components itself isn’t exactly clear. It could have been buying in subcontracted pressings from a likely Italian motor cycle metal press specialist like Peripoli, and then simply assembling the parts, but certainly Casalini had a major involvement in the various David scooter variants across Europe in the late 1950s.

David Type B

The scooters seemed to lead to a varied range of transporter mopeds and light motor cycle commercial carrier models by 1960. This appeared to be the niche in the market that Casalini was looking for, and the company has largely been specialising in the super-light commercial and miniature-auto sectors ever since.

‘Motocarri’ three-wheeled light commercial vehicles were popularly produced throughout the 1960s.

Casalinifabriken introduced a series of moped based microcar models in 1969 and is reportedly considered the oldest microcar producer in the world! Really? Perhaps the interpretation of that may be the oldest microcar producer in the world that is still manufacturing?

While carrier mopeds became a fairly normal sight in continental Europe, they really didn’t catch on in Britain at all, so are perceived as something of an oddity in this country. One of these vehicles is certain to attract curiosity, and aspects of their construction can involve a fair degree of puzzlement and getting your head around.

The Casalini David PT seems to be an odd combination of light commercial carrier and sports 50. It first came to us for registration, and we dated it to around 1970; Casalini being the make, David being the ‘brand’, and PT for ‘Priemoné Transporto’ = ‘vehicle intended for the carriage of freight’ (ie: Trade Carrier).

With the whole chunky cycle chassis construction and carrier frames at both ends, you’d probably be expecting it to be married to a low revving and high torque, ploddy commercial engine—instead it’s installed with a buzz-bomb Minarelli P3!

This particular P3 motor is a kick-start version, and the Casalini frame is fitted with footrests, so back in 1970 this would have been classified as a 50cc motor cycle for registration and licensing purposes, and would not have qualified as a moped at that time.

The front carrier, 340mm square, comprises a sub-assembled and removable mounting bolted to the main frame, while the rear rack 340mm (13½ inches) wide × 430mm (17½ inches) long has its entire carrier tube structure comprised of integral welded components of the rear frame assembly.

If you might be puzzling over why there’s an unlikely hole through the lower seat-post part of the frame that seems to be doing nothing other than holding a tax disc holder in place, this fixing point would have originally been for a small round toolbox.

The chassis runs on chunky 3.00×12 tyres & rims, laced onto what appear to be enormous ‘commercial’ size hubs in comparison to the general scale of the rest of the machine.

Earles type front forks with the same suspension units are deployed front and rear, and though it may look as if the forward swing arm pivots off the front mudguard, it’s not so: there’s a structural formed tube neatly concealed within the front guard.

Starting is easy, just turn on the fuel, snap down the choke lever on the Dell’orto SH14-14 carburetter, which will automatically release when the throttle is opened full, one jab on the kick-start and the motor fires up first time—then dies out again as soon as you try to open the throttle.

We’re warned that the motor doesn’t pull at low revs very well when cold, so we sit warming the engine for quite a while before attempting to pull off—and it still doesn’t pull at low revs, so we have to scream up the revs and feed in the clutch. Typical Italian sports moped motor, all top-end and no torque; this doesn’t seem particularly suitable for a trade carrier? It’s a bit like putting a race-car engine in a truck!

That business of ‘feeding in the clutch’ isn’t quite as simple as it sounds … the Domino hand change turns back towards the rider for first, when the clutch lever is pointing upward, and your wrist probably won’t be able to let your hand grip at that angle, so you’re half working the lever in your palm with your fingers on the grip. This method also proves a little more practical to keep the twistgrip held back, since the gear is only locked in by the lever when the clutch is fully out, so all the time you’re feeding the lever in, you still have to hold the gear from jumping.

You’ve barely got the clutch released in first for a quick burst on the throttle, before you’re pulling it back in again for the next gear. Now you need to hold the twist-change forward as you feel and gnash for second, you might need to keep the grip twisted forward or the gear may kick, then another quick burst of throttle before the relief of switching to third and top-on-the-stop.

The motor’s reluctance and tendency to die off at low revs does lead to some wonder if the carburetter set or fuel supply might not be right, and the lack of tractability does make riding control somewhat more difficult, but is often not untypical of this sort of motor.

Acceleration is noticeably peaky as the motor comes into its power band, then goes onto howling revs that seemingly have no limit. All the while, the thrashing revs are accompanied by an only lightly suppressed induction roar from the meagre air filter baffling, and a tinny snarl from the exhaust.

This is a pretty noisy machine to ride, and you can’t do that subtly! To many old-time riders, it feels as if the engine may be shrieking itself to death but these motors supposedly thrive on high revs and you’d probably be labouring the engine if you tried to ride ‘normally’.

We also discover that the three-speed Domino hand change delivers somewhat ‘variable’ gear selection, in that sometimes it was in, sometimes it was out, and sometimes it wasn’t there at all—which seems to account for the stereotypical Latino howling of revs, crashing of mis-engaged gears.

Most practical and comfortable cruising seems to be found up to 25cc, otherwise the motor seems to be buzzing too much and the incessant revs become quite wearing. Below 25 the exhaust tone is murmuring just off the boil and the steady pace is more tolerable.

We found the fore-carrier a little distracting when riding the bike, since it didn’t appear to be mounted quite square to the front of the frame, so cruising along the main straight gave a false impression that the steering might be ‘off’!

Push beyond 25 and the motor starts howling away like some demented insect, up to a best on flat of 36cc.

The full crouch downhill run of 42cc was accompanied by a devastating banshee wail of unnatural volume and revs, as we urge the now highly enraged machine round the lower bend, through the dip and into the uphill climb—we certainly wouldn’t have wanted to try that with a full load aboard the carriers!

It’s almost a relief as the howling revs fall off on the following ascent, dropping to 26cc as we crest the rise, but still maintaining top gear all the way up.

The run was accompanied and clocked by our usual pace bike, since the David PT was not fitted with a speedometer.

With the combination of small diameter wheels and large commercial hubs, braking was always very capable, though the cable operated rear footbrake lever seemed a little basic, small and not so readily found by feeling around with your foot, so sometimes needed a glance down to find its position.

Suspension springing felt firm at both ends, so the shocks are presumably rated for a commercial load, and the bike feels noticeably over sprung when riding without any ballast.

The small fat tyres resulted in a somewhat vague and fuzzy-feel handling, with relatively little feedback from the road, though the bike would stay well enough on the intended course as long as you concentrated on steering.

The Casalini David PT is really not the sort of machine anyone is likely to choose for recreational use or enjoyable riding qualities. As a light commercial bike, it’s probably something you suffer through if you have to ride it in a delivery rôle, until you have an almost inevitable accident and wreck the thing, or explode the engine, or break the gearbox.

From 1971 Casalini popularly produced many thousands of 50cc Sulky micro-cars (which did not require a driving licence in some continental countries), and were also available in light commercial body styles, then subsequently two other micro-car model variants, the Minivetture and Vetturette.

Since 1994, Casalini Inc has been producing light ‘quadricycles’ called Ydea, to Italian state specification 92/61 EC, and approved for export and use across EU states. These are micro-cars having a steel frame and glass-resin bonded safety body shell with fitted windows, four-wheel suspension with disc braking, and limited to maximum 45km/h performance (28cc).

In 2005 a new and modern Sulkycar quadricycle for light freight transport was introduced.

In saying earlier that Trade Carrier mopeds ‘really didn’t catch on in Britain at all’, we didn’t mean that nobody tried to sell any over here … because, unlikely though it may seem …

The original AJW motor cycles company was established at Exeter by Arthur John Wheaton in 1926, and built its first production model with a 996cc British Vulpine V-twin engine.

Approaching the Great Recession of the early 1930s, A J Wheaton was astute enough to recognise looming signs that demand for big and expensive motor cycles was on the wane and, for his 1930 range, began to introduce lightweight and economical Villiers-engined models to replace the declining sales of large capacity machines.

All the bigger V-twin models and two-stroke lightweights had ended by 1932, leaving 350 & 500cc single machines for 1933, then just 500s from 1934.

AJW limped through the tail of the recession toward the end of the decade (which was better than a great many other motor cycle manufacturers fared over this period), with just one 500cc model for 1938, before emerging to a couple of new 250cc Villiers two-stroke lightweights in 1939—just in time for World War 2 to close proceedings in 1940.

The firm changed hands in 1945 when the founder sold out to Jack Ball, who firstly relocated it to Bournemouth, Hampshire, then on to Wimborne in Dorset.

Production using JAP-engined models returned in 1948 on a limited scale, with a Speed Fox speedway bike, and road-going Grey Fox side-valve twin that was dropped in 1950. A 125cc JAP-engined Fox Cub two-stroke was briefly listed for 1953, and further offered a built-to-order 500cc JAP single, but both concluded as their engines became discontinued later in the same year. The speedway model remained in production up to 1957, when JAP was bought out by Villiers, who promptly closed down its remaining engine manufacturing. The Birmingham-built Hercules Her-Cu-Motor moped similarly became a casualty due to loss of its unique 50cc JAP engine, and the moped chassis design being totally unsuited to the installation of any other engine.

To continue the business, AJW switched from trying to manufacture machines itself, to factored importation of Italian built Giulietta 50cc Minarelli-engined light motor cycles and mopeds up to 1964, when the business seemed to go into mothballs for a decade, before resuming in 1974 with a new range of AJW-branded imported Italian Minarelli-engined mopeds and light motor cycles up to 125cc. The Iceni CAM library holds literature files from this time listing new business address details as: AJW Motorcycles Ltd, Crowvale Depot, 8 Stone Close, Horton Road, West Drayton, Middlesex.

Our 1976 registered AJW Collie is clearly based upon a Giulietta Transporto model, except the Giulietta is notably a kick-start & footrest type 50cc motor cycle in a similar manner to the Casalini David PT. The AJW is distinctly different from these Italian market cousins, since the Collie is a pedal moped!

From 1957, Giulietta was the own market brand label of Peripoli metal and press works at Alte di Montecchio, Vicenza, and by 1965 ranked as the seventh largest Italian motor cycle manufacturer. While the business mainly engineered for its own badge, it also supplied component products for other trade customers.

We’re not sure whether Peripoli–Giulietta Transportos were also normally available in moped form, or if the Collie moped carrier was a special variation produced specifically for AJW, but the Collie must have been just a token listing in the UK and AJW really can’t have sold many.

The chassis has a stubby 40½-inch wheelbase, and 63-inch total length end-to-end of the front and rear racks. Similar to the Casalini, the rear rack comprises a welded part of the frame assembly, but the front rack is removable by two bolts.

The forks are equipped with Earles type front suspension, with swinging arm rear, and using the same undamped spring units at both ends.

Cast aluminium Grimeca hubs are bolted into steel disc wheels, which still appear to be shod with their original 3.00×12 Pirelli Ciclomotore tyres, so it doesn’t seem as if our example has had much use.

Our Collie Carrier is fitted with a pedal type Minarelli P3 engine with three-speed hand-change gears and Dell’orto carburetter, so again likely to be more banshee than truck!

The Rolle Milano 60cc speedometer plainly isn’t going to work since it has no cable, so plays no further part in the proceedings.

Even before we’ve got underway, we’re thinking that several aspects of the Collie controls seem pretty insane, maybe even bordering on the dangerous, and most of our concerns particularly relate to operation of the heel-back rear brake from a moped pedal set! We might like to think about quite how that one may work for a moment…

The fuel tap is at the bottom left of the tank, push on the choke, which lifts off as the throttle is opened, and after a couple of dead prods on the pedals, the Minarelli suddenly bursts into life. As expected, the P3 motor is all snappy response and howling revs, hardly what you really want for commercial carrier? Surely some docile and torquey plodder would be much more appropriate, and we fondly recall the old Trade Carrier Autocycles tested back in October 2008.

First gear selection with the Domino hand change finds effective location inside the P3 motor, the clutch feeds in smoothly, and then we’re away and screaming up the road. Twist forward and feel around for second, then wring the shift on halfway round the bar for top.

It’s all howling acceleration and gnashing of gears to engage the selection, then more howling acceleration and wrestling the twist change for yet more howling acceleration—just to get up to a happy cruising speed around 30cc, where you can finally settle back the throttle and take a moment’s breather while the exhaust murmurs away behind.

Twitches on the throttle are instantly responded to by an induction wail from the carburetter intake, and an urge from the motor which can take you up to between 34 and 38 on flat according to conditions.

Pace bike clocked best downhill at 39cc.

Both brakes prove effective enough, but operation of the rear brake proves somewhat handicapped by the combination of pedals and attempted operation of the heel-back lever.

Probably Collie’s most concerning aspect is that with a pedal at the bottom of its stroke, clearance is just 1½ inches to the road, then with a rider aboard, and carrying a load, that’s only likely to get closer!

Things really don’t work too well if you completely transfer your right foot to the heel-back brake lever, because then there’s nothing to prevent the pedal set from free-rotating from underneath your left foot and potentially pitching you into some cornering disaster, so you end up ‘hovering’ your left foot just to try and stop the pedals going round.

The pedals can become worryingly near to grounding in down position on just average road bumps, as the suspension bounces even on the straight, and it wasn’t long before we experienced a low speed pedal-grounding moment during a turn in the road. When a rider survives one of these heart-stopping ‘grounding’ moments, it’s going to leave an indelible stain on the memory to generally ride with the pedals in level-set, and bring the respective side up into bends.

Trying to manage on the front brake alone wouldn’t be any solution for a normal moped, but the prospect of riding a laden Collie in traffic using only a front stopper would surely be plain suicide! The reality is that you have to use that rear brake, but operating the heel-back pedal seems just about as hazardous as not using it!

To be able to find and operate the back lever effectively, you really need to ride with the right pedal arm set to the rear, and the ball of your right foot on the pedal, then you can just about keep your foot on the pedal while still operating the rear brake with your heel. It’s uncomfortable, but just about the best way to work a bad situation.

Handling the Collie is no pleasant experience, it performs well enough, but the short wheelbase cramps the riding position, and makes cornering awkward. The suspension is over sprung without a load aboard, so the bike pitches and bounces about on bumps. The wide twist-arc of the three-speed hand change becomes wearing on the wrist, and the rear braking arrangement is nothing short of deadly.

‘But just think of the added advantages in having a company vehicle to use in out-of-work hours’

‘No thanks, I’d rather take the bus!’

The entire AJW imported range was de-listed in November 1976, whereupon J O Ball Ltd seemed to have sold on the AJW name to Chinwood Ltd, 80a Weyhill Road, Andover, Hampshire, SP10 3NP.

Peripoli ended its business in the late 1990s.

Next—Broadsword calling Danny Boy, The Eagle has landed—except in this case it’s more like a big old Turkey that’s landed instead!

This article appeared in the

October 2013 Iceni CAM Magazine.

[Text & photographs © 2013

M Daniels. Period documents from IceniCAM Information Service.]

Other carrier mopeds are available … this is a Gerosa.

Despite the size of the finished Priemoné Transporto article, the feature technically became graded into ‘oddball’ spot due to the unusual nature of its content.

Though carrier mopeds were widely popular for trade use across many continental countries, they never caught on at all in the UK, and are consequently as uncommon as their trade carrier autocycle predecessors.

We originally encountered Charles Sylvester’s Casalini David PT as a dating-for-registration in August 2011 and, once completed, the bike was generously offered for feature. A run up to Leicester to collect, test and photoshoot the bike in August 2012 (with another for added value, see Sheep in Wolf’s Clothing—coming shortly), then canned until some time when we might figure out how to present the article. That suitable moment seemed to arrive as our ‘world tour’ series crossed the Adriatic to Italy, so the PT title and leader was dropped into a ‘Next’ from CAM 27. There was a lot of difficult thinking about how the PT article might be structured … then a plan seemed to come together to match it with another long submerged test on the AJW Collie carrier moped, which had actually been sitting on file for over four years!

We’d incidentally tested Luke Booth’s AJW way back in September 2009 when he brought it up for display on the EACC–IceniCAM stand at Copdock Show of that year; but with little idea how to present this in a feature at the time, the notes filtered down to the bottom of the box, where they remained, practically forgotten for all these years. The Casalini David was prettily painted and certainly attracted attention. The unusual AJW Collie also generated a lot of interest, but neither bike was particularly easy or pleasurable to use due to their difficult hand gearchange arrangements, and inflexibility of their Minarelli P3 engine power characteristics for the carrier application. Riding the Collie was further complicated by to its moped arrangement with a heelback brake lever—what a diabolical control plan that was! Whoever thought that up for a trade carrier application must have been plain bonkers! With a conventional kick-start & footrest layout, the Casalini was much more sensible and practical, and given a foot-change motor instead of the cranky hand-change arrangement, then it could have been fine, but neither of these bikes were the sort of machine anyone might be likely to run for ‘leisure use’. You’d really only ride them if you particularly wanted to transport something, and when it came to the final call—we preferred the old Levules, James, and Norman Carrier Autocycles from In the Trade.

Production of the PT feature involved around £50 in diesel fuel to collect & return the Casalini to Leicester, while the AJW from Hastings involved no further expense since it came to us and was collected by the owner—in all a fairly cost effective article considering the unusual and interesting nature of its content. Sponsorship became credited to Suffolk Section EACC enthusiast, David Whatling.