Out of fuel, our capsule plummets back towards Earth. Upon hitting the atmosphere, drogue parachutes operate automatically to slow the descent and we gratefully drift towards the ground, to finally land in a damp field somewhere in northern Yugoslavia.

We so very nearly made it to Austria or Italy, but no such luck, and now we seem to be stranded behind the Iron Curtain! It isn’t long before soldiers arrive to transport us to a military compound where we are taken to a sparsely furnished custody suite, to await our interrogator.

We hear the sound of jackboots marching down the corridor, and know the moment has arrived. The door bursts open and two armed guards escort a plain clothed official, who pulls up a chair to sit at our table, opens a glasses case from his pocket, and arranges a pair of battered, wire rimmed spectacles across his nose. ‘We know who you are. You westerners think things are so backward in communist states, but we also have the Internet in Yugoslavia. You are from the Iceni CAM Magazine and we have read of your exploits … maybe you have come to compare our products against those of the west? We will be most happy to introduce you to our local moped factory … welcome to Slovenia!’

After World War 2 the country’s communist government was seeking to develop new industries, and a business was established in July 1954 when a licence agreement was contracted with the Austrian Steyr–Daimler–Puch company to produce and supply branded Puch moped models into the Eastern European market. The robust and economical small capacity Puch geared models were particularly suited for use on the gravel roads and steep terrain that characterised the region, and Puch further offered very favourable licensing terms as it doubted the business would ever be capable of operating independently.

In August 1954 the name Tomos appeared in company documents for the very first time, its name being an acronym made from the words TOvarna MOtornih koles Sežana (Slovenian for Motorcycle Company Sežana). In October 1954, the Slovenian government began construction of the Tomos factory outside Koper, a coastal industrial township, where the primary business still remains today.

Production from temporary facilities started in 1955, and the finally completed main factory was officially opened in 1959 by Josip Broz-Tito, then President of Yugoslavia. The first Tomos branded product was a motor cycle based on the Puch SG 250cc split-single and, in 1955, Tomos assembled 137 of these machines, along with 124 Puch RL 125cc scooters and 100 mopeds. It was the economical moped that proved the most popular and 1,712 were built in 1956, as well as 615 motor cycles and a further number of scooters. Along with licensed assembly of Puch MS50 moped products, Tomos also started to produce its own-version ‘Colibri’ models, which became serialised in types T01 up to T13. Over 17,000 Colibri mopeds were produced in 1959, and Tomos signed its first major contract for export to Sweden.

With declining sales of motor cycles across the European market in the 1960s, and many established trade manufacturers experiencing difficult times, Tomos decided to concentrate exclusively on production of 50cc two-stroke models. Dutch sales of Tomos mopeds became so significant that, in 1966, the company established its first factory in another country: at Epe in the Netherlands, to cater for direct service and supply into this important market.

Towards the 1970s, as imported western European components were becoming progressively more expensive to purchase in eastern communist states, Tomos started preparing of its first own-design for production. The A1 automatic moped was a basic single-speed engine in a proprietary step-through frame.

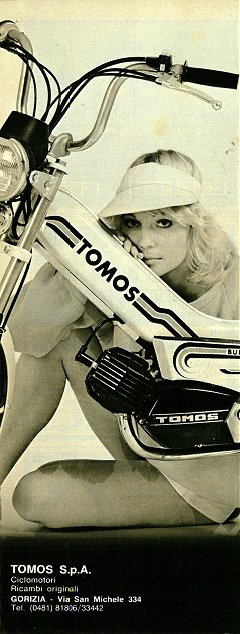

The A1 was succeeded by the A3 model in 1973, completely designed and manufactured by Tomos with a new two-speed automatic engine in their own moped frame, constructed by automated robot welding equipment and produced from a new and modern production assembly line. Introduction of the A3 presented a clean break from 18 years of licensed Puch based models and, after 1973, all Tomos machines would be equipped with in-house manufactured engines. Newly introduced Colibri 14V and 15 models also presented a further Tomos foot-change geared light motor cycle engine, though the cycle frames still appeared to be based on established Puch design.

Increasing living standards in the 1970s also presented a new generation of young buyers with high disposable incomes, popularly leading to a number of ‘custom’ A-OS, A-ON and A-PN moped models with high handlebars, cruiser saddles, pannier accessories, and extensive chrome finish. 1976 introduced the first sales of Tomos mopeds into America through established US distributors who were already selling various other European makes into the Stateside market. This moped boom hit its peak in 1979 as the OPEC oil crisis emphasised consideration of fuel efficiency and economy. These times however wielded a double-edged sword, as now for the first time, Tomos was faced with restrictive environmental standards to consider, and needed to modernise its products with emphasis towards regulating noise and reducing emissions.

It’s at this point we meet our first Tomos tester, a silver two-speed auto A3 model dated 1984. Its specification is given as 38mm bore × 43mm stroke with 8.5:1 compression ratio and rated 2bhp@5,500rpm.

Earlier Tomos engines were initially designed as pedal mopeds and subsequently adapted to kick-start and footrest equipped ‘sloped’ specification as the regulations changed, but obvious witness where the old pedal shaft went through still remains on the A3 motor to indicate its history. We’ll not be expecting a sparkling performance since a ‘sloped’ plate on the frame indicates 30mph compliance, and gives weight at 45kg, which at least saves us from getting out the scales.

With spoked wheels on chrome plated rims and tyres sized 2.25×16 the Tomos maintains a ‘traditional moped’ look, and the cast alloy hubs present something of a quality touch in comparison to typical Italian market pressed tin hubs of the period. The speedometer and headlamp are ‘joined’ at the headstock by a plastic moulding that makes it appear like a nacelle style assembly, which is easily adopted by the eye so that it may not be appreciated this is no more than a simple trim.

The fuel tap off–on–res is tucked at the bottom right of the frame/fuel tank, just in front of the side panel. The 12mm Encarwi carburetter choking function is rather unusual, push the black thumb button on the throttle away from your hand, and turn the throttle forward to ‘extended’ range. The choke function will automatically disengage when you open the throttle again, and the twistgrip returns to normal range as the thumb button re-engages the choke latch. The left-hand kick-start is quite unnatural and clumsy to operate while you’re sitting on the bike, so most riders are likely to dismount and stand on the left side of the bike to kick with their right foot. A couple of jabs on the starter soon have the motor fired up and we leave the bike to run a little before blipping the throttle to clear the choke.

For pulling away, there’s nothing to do except turn open the twistgrip and lift your feet onto the footrests. First gear range runs up to around 15mph, when the bike seems hover on a plateau of revs for a few seconds while it hesitates … to think about the up change … will it … yes, alright … before lurching into second and surging forward again in top ratio. The Tomos two-speed automatic gear change is actually something that can add a little interest to the largely uneventful performance, since you can induce a timely and quicker up change by backing off the throttle at the crucial point as the revs peak out, so effectively skipping the ‘automatic plateau’ phase. Much the same can be effected on the down change for hill climbing if you find the revs bogging down with the auto locked in second under load, just momentarily back of throttle and it can similarly be ‘switched’ back down to first.

Early exchanges with our pace rider quickly established the Tomos CEV speedometer seemed to be consistently indicating low throughout the bike’s range, so comparative readings were recorded at all key points of the test run. Best on flat in upright stance paced at 30mph (Tomos CEV speedometer reading slow, indicating 25). Best on flat in crouch paced 32mph (speedometer reading 27). Downhill run paced 35mph (reading 30).

Uphill dropped back to actual 22 (reading 16–17), at which the speed hadn’t dropped enough to initiate an automatic change back down to first so still managing to crest the rise in second. Even with a heavy rider, the low first ratio would probably be capable of getting the bike up pretty much any steep hill … but only slowly and steadily …

We observed some quite erratic readings from our Tomos 40mph CEV speedometer. It generally seemed to be indicating around 5mph slow, and suffered periodic fits of wild needle swinging, so really wasn’t an instrument to be trusted on this bike.

The kick-start engine seems to rev fairly smoothly, but you quickly become aware of a high frequency vibration tingling through the footrests, handlebars and seat. Also noticeable is a low level of indefinable mechanical noise from the motor, and there’s always a bit of a feeling that the quality of engineering inside might be slightly ‘loose’? It’s not that there’s anything wrong with this original condition and low mileage example either—our Tomos aficionados tell us this ‘loose mechanical’ impression is quite typical and normal.

General handling and brakes were OK, so the bike could be pushed along consistently to maintain a steady pace. The silencer note was fairly mellow with a definable subdued popping emanating at lower revs, and the exhaust tone was always moderate, discrete and pleasant, so wouldn’t attract undue attention—unless someone maybe took a hacksaw to the baffle. The foam moulded saddle was generally quite comfortable apart from the progressive intrusion of vibration if you’d been riding it on throttle for some time.

As you’d probably expect, there’s a number of proprietary fittings on the A3, with Magura controls, CEV 6-Volt AC direct lighting set with brake light switching powered from an Iskra magneto flywheel generator (licensed Bosch copy), and CEV speedometer set.

The Tomos A3 is generally a fairly bland and uneventful machine to ride, doing what it’s supposed to do in somewhat crude and plodding manner, though with some character in the ‘basic engineering’ of its eastern-bloc style ‘value-for-money’ engine, and the way the two-speed auto-gear can actually be manually changed by throttle control. One of the cheapest 30mph budget mopeds in its day, the Tomos A3 probably represented quite good value for money at the time.

The Tomos two-wheeler range received on-going model updates throughout the 1980s to be popularly competing for international sales. A new generation of 50cc motor cycles was launched in 1985, the BT50 with cast alloy wheels and indicators, and its off-road use derivative, the ATX50C trail model. While the Tomos business was on its way up, the now fading Puch company was on its way down, being bought out by Piaggio in mid 1987, which immediately ended the production of all Austrian Puch models.

Entering the 1990s, Tomos USA became established at Spartanburg, South Carolina, in a new office and warehouse complex of over 24,000 square feet, to cater for increasing sales and distribution into the important North American market. A new Tomos moped engine variant was introduced called the A35, which was still based upon the A3 motor, but featured a new big-fin top-end with reed-valve induction, and higher power rating of 2.4bhp@5,200rpm. The A35 motor also introduced a number of new and restyled models, the Sprint, Targa and Targa LX (subsequently re-designated ST and LX).

Now we meet our second Tomos tester, a blue two-speed auto A35 Tango model dating from 1991. Its model plate indicates type A35UA, and the spoked wheels from the earlier A3 model have now given way to cast alloy wheels of the same 2.25×16 size—and we have to say that they do look nice. Their white finish really sharpens up the impression. Apart from a few small detail changes, the chassis is exactly the same as the A3, but the A35 looks much more modern from a number of component and trim changes that work really well to enhance the appearance.

From most angles, photoshooting the Tango did seem particularly easy for the camera. Once the bike was lined up in the viewfinder, the shots just seemed to fall straight into place-basically because the A35 is quite a photogenic machine!

The original A3 engine was a very traditional piston-ported motor with relatively small finning on a cast iron cylinder and alloy head. With its big-fin alloy cylinder and head, and reed-valve induction, this later A35 motor certainly looks more businesslike, but probably only represents cosmetic muscles, since both machines are still technically restricted to the same specified 30mph ‘sloped’ performance-so we do have to wonder whether anyone might really be expecting it to perform much differently?

The fuel tap turns on at the bottom right of the frame just ahead of the side panel, but choke operation is different on this model due to a change in the fitted carburetter. The A3’s Encarwi has been replaced by a Dell’orto, which has a lever-lock choke clicked on through a small access port in the right hand side panel. The same left hand kick-starter arrangement still feels unnatural and clumsy on the Tango, but a few irregular jabs at the starter promptly get the motor growling and whining into life—ooo-err, it doesn’t sound happy! There’s a high level of mechanical noise, gear whine, and rattling of internal gear backlash, which immediately serves the impression of some poor engineering quality.

We leave the motor to run a little, then open the throttle to clear the choke … the motor runs on, rattling and whining … might it sound any better as we leave it to warm up … no it doesn’t!

Our bike was apparently quite a low mileage example when the present owner acquired it, primarily for use as a going-to-work commuter, so reports it suffers regular use and abuse, with maintenance generally limited to essential repairs. It apparently used to be noisier in second gear, but while second has quietened somewhat with use, first ratio still sounds just as bad—not particularly confidence inspiring … Engine oil changes have reportedly made no improvement to the issue, but despite all the mechanical protestations, the motor has continued to function reliably—it’s just noisy.

Accelerating away seems a little more positive and responsive than the earlier piston-ported A3 type. A35 feels to pull a little better from low down, which is probably what would be expected from addition of the reed-valve induction. The engine noise is terrible, loose, rattly, and the gear seems to whine and screech even worse under load! Revs peak in first ratio in much the same manner as the earlier A3 motor, hovering on the plateau for a few seconds at 15mph, before lurching through the automatic change into second, where the acceleration phase resumes again, up to indications generally between 30–35mph.

With two pace bikes tracking our run, exchanges with both pacers quickly confirmed inconsistencies with our A35 Facomsa speedometer; indicated 30mph was confirmed as actual 27mph by both pace bikes, and indicated 35mph was confirmed as actual 30. Best on flat in upright position indicated 35, actual paced 30. Best on flat in crouch indicated 37–38, actual paced 32mph. Our downhill run pushed the needle well beyond the end of the 40mph dial, indicating somewhere around 45ish, at which the two tracking pace bikes agreed 38mph. The following uphill section saw speed fall back to actual 22–23mph before cresting the rise.

Braking and general handling proved pretty reasonable. The A35 could be ridden hard up to corners and put round with a moderate degree of confidence, though was neither what we’d call firm or tight, but still fairly rideable, and capable enough to press a consistent pace. Our general impression was that the reed-valve A35 might fractionally outperform the older piston-ported A3 by slightly stronger acceleration and a little more pull on hill climbing, but running the two bikes together didn’t quite work out as expected! While the A35 accelerated away, the A3 just tucked in behind to stay right with it, sometimes managing to creep up enough extra pace in the slipstream to even overtake the Tango … which promptly tucked back into the A3’s slipstream and returned the manoeuvre.

We just declared the match a draw!

Starting in 1991, the Yugoslavian union began to disintegrate in a series of state civil wars. Slovenia declared independence on 25th June 1991, and Slovenian Territorial Defence fighters fought a brief 10-day resistance of blockaded barracks and roads, leading to stand-offs and limited skirmishes around the republic against the JNA Yugoslav People’s Army, before the Brijuni Accords peace agreement was signed on 7th July 1991.

Due to its geographical position in the north of the country, the nature of difficult mountain terrain limiting military access, and disposition of the Croatian state to the immediate south acting to some degree as a buffer zone, Slovenian independence was gained very lightly compared to the experiences of other Yugoslav states, and general business at Tomos was largely unaffected by the on-going troubles around it. Tomos remained a state owned enterprise up to 1998, when it was privatised in a sell-off to the Slovenian Hidria Corporation.

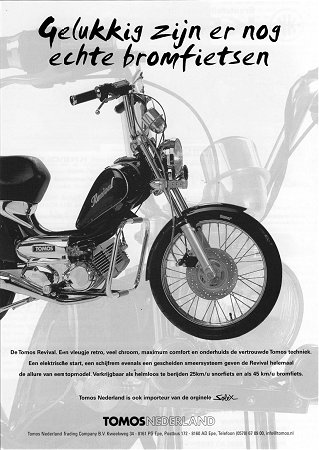

In 2004, Slovenia became admitted into the European Union, and Tomos contracted with BMW to produce component parts for some of its vehicles from the Koper factory. In 2006 the A35 moped motor became succeeded by a new A55 engine version with lighter rotating parts, rated with a higher power output, and delivering improved EPA emission standards. Introduction of the A55 engine complemented a new range of moped models in the Arrow, Revival, Streetmate, and MC off-road line.

Since being established, Tomos has diversified to production and distribution of a number of other motorised products into Eastern European markets, covering motor cycles, boats, outboard motors, and cars, including distribution of Renault and Citroën models for home market sales. The A55 engine continues to be used in all current 50cc applications, and following a sales gap of 20 years, Tomos moped models returned to UK listing from 30th July 2013 … though it has been a while, and things have changed …

When Tomos moped models were previously being sold into the UK and other world markets, they were then produced from an Eastern European communist state with a lower cost base, so enjoyed some considerable advantage of being able to sell very cheaply, and significantly undercut other Western European moped competition.

Today the wheel has turned full circle, and now the Slovenian standard of living has risen to parity with the EU community. The commercial advantage is now dramatically in the purse of Asian manufacturing and despite the current popularity of ‘retro’ style 50s, Tomos is probably now going to find it quite difficult to sell its latest Classic XL45 mopeds listed at their £1,395 price tag, in a market already flooded with much cheaper moped products coming from China. Who knows how things will go? Watch this space … perhaps Tomos GB Ltd might let us have one of those nice Shadow Black ones to test and say nice things about?

Next—How many former armaments manufacturers turned to making motor cycles? Answer: a lot!

This on-going quest of mapping the moped world takes us on a ride across the Alps, to Germany where our next edition will focus on some of the Gothic giants of moped manufacture.

Our next main feature could ‘combinette’ the right ingredients to explode with a bang! We test two of this company’s earliest moped models—and this is Detonators!

This article appeared in the

January 2014 Iceni CAM Magazine.

[Text & photographs © 2014

M Daniels.]

There were several local Tomos owners who’d been badgering us to do a Tomos feature for quite a while but, for some reason, we hadn’t managed to work up much enthusiasm at the prospect. Maybe the general stereotype of budget, Eastern-bloc, ’80s–’90s sloped/mopeds just wasn’t inspiring us. Over a period of time however, the Tomos lobby kept unrelentingly grinding away and, in a moment of weakness, we sort of agreed. While that temporarily defused the immediate pressure, it wasn’t long before they were coming back again asking, ‘when might it be done?’, and ‘when would we take the bikes?’ Eventually wearing us down, and in another moment of weakness it was finally agreed ‘alright, enough, next edition’ … which meant the bikes going through road test and photoshoot amid a whole load of other Autumn tests, with Anthony Brown’s A3 in October, and Pete Fisk’s A35 in November.

To be honest, the bikes weren’t as bad as we thought they might seem. OK, the motors were a bit loose and rattly, but that seems to be a characteristic of the breed, and yes, they are fairly bland slopeds that pretty much only do what they’re supposed to do (30mph), but they started on cue, completed the course OK, and seemed to do everything that was expected of them without any drama, so that was OK. Collating all aspects of the research enabled the text to come together into a very rounded and structured story, with a novelty angle on the introduction, and a conveniently timely conclusion as Tomos had just returned to UK listings in the summer of 2013, following a gap of 20 years. The commercial summary at the end offered the title, and when completed, we were fairly satisfied that Full Circle worked out a well-balanced and complete article in its own right.

Who would have thought that we’d ever be presenting a Tomos article as the lead feature, but there you are! Since both bikes came from local sources, production costs were quite minimal, and sponsorship credit was attributed to a modest donation from Bournemouth cyclemotorist, Grant Keay.