Sponsored by Harold Wright,

East Anglian Cyclemotor Club

Suffolk Section.

Scooters ... when did they start?

Generally, credit may point towards introduction of the Piaggio Vespa in 1946 as herald of their growing popularity in modern times, but it's easy to quote many veteran examples such as the American Autoped (1915), British Autoglider, Reynolds Runabout, ABC Scootamota (1919), and Grigg (1920).

Early sccoters: ABC, Norlow and

Grigg

Scooters actually go back quite a long way, but what the Italians achieved after the war however, was to build their machines with a stylised body, which is when the scooter really took off.

The new BSA Beeza scooter

reported in Power & Pedal.

Slow to appreciate the significance of the modern scooter, British manufacturers were somewhat left behind, and in belatedly trying to adapt and improvise traditional motor cycle construction assemblies, produced (it has to be said), some fairly gruesome efforts.

The handicap of many of the British scooters was that they were invariably created from a base of available market components. Using typical Villiers engines designed for motor cycle applications, crudely adapted into primitively panelled bodies, these completely failed to match the Latin design flair.

The essential key to enable a stylised scooter was primarily a purpose designed unit engine.

The BSA 'Beeza' prototype scooter presented at Earls Court Show on 12th November 1955 never realistically offered any practical production prospect with its 'concept' side-valve engine, but represented an important change of tack, in appreciation of the principles required to create a competitive scooter, and a belated acceptance of the necessity to commercially compete in this important and growing market sector.

So, under the shadow of Edward Turner, the design office began drafting plans for a range of production scooters...

The new BSA-Sunbeam/Triumph

scooters

reported in Power & Pedal.

After a lengthy development period, the first truly competitive British scooters were presented and launched in 1958, but it was 1959 before the badge branded BSA Sunbeam B2 & B2S (electric start), and Triumph Tigress TW2 & TW2S (electric start) 250cc four-stroke twins were delivered for sale. It was nearly 1960 before these models were complemented by the addition of another BSA Sunbeam B1 175cc two-stroke single scooter, with a motor derived from D7 Bantam components and a four-speed gearbox based on C15/Tiger Cub parts.

Working a stint at AMC Motorcycles since April 1955, Bert Hopwood agreed a return to BSA Group as Director and General Manager in May 1961 and introduced by Edward Turner (notable as designer of the Ariel Square Four and Triumph Twin, now Managing Director) as, "A very lucky man to come in at this stage to the next scooter project, having missed all the worry and hard work, and to have a job so very much simplified by a ready made and long awaited newcomer to the Triumph range of products".

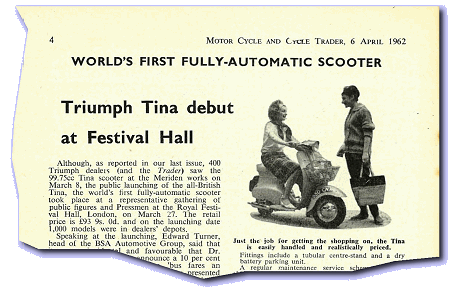

Tina's launch reported in the 'Trader'

The project scooter was already being prepared toward production, to a date set by Turner in early 1962 for the official launching of this new model at Meridan, with most of the dealers invited for the grand ceremony, to be followed by a buffet luncheon in a great marquee erected on the front lawn at the works.

It shortly became apparent to Mr Hopwood however, that testing of the model wasn't quite as far advanced as the plan to put the bike into production ... in fact, there had been virtually no prototype testing of any sort!

It transpired that no working sample had been made available to the Experimental Department, since the only functioning model had been withdrawn from development for styling and catalogue purposes, so Hopwood immediately ordered three prototypes to be built, regardless of cost.

This brand new scooter project concerned not just an unusual and original frame concept with completely new 100cc two-stroke engine, but also the company's first automatic constant variable transmission (CVT) set and, still stinging from the ongoing BSA Dandy debacle, it might seem quite remarkable the situation had progressed to the present stage.

The advanced project had already embraced massive capital investment involving huge tooling costs and the building of a complete new wing at Meriden Plant housing a semi-automatic assembly line, ambitiously capable of production well in excess of 1,000 units per week.

A new product was about to be launched, for which a running prototype did not even exist, and Bert Hopwood was realising a vision of imminent disaster. He later reported the project to have caused so much anxiety and despair that, at one particular stage, he seriously considered making a run for it and buying a small business!

The whole thing was an utter management mess: the dealer convention should really have been postponed and the launch delayed, but the notices had already been posted by the time the situation was exposed - and it was already too late call things off.

The day before official launch, Edward Turner announced that he was off to California, and nominated Bert Hopwood to host the ceremony in his absence - leaving him just twelve hours to fully acquaint himself with the design, and blag a reasonably convincing presentation...

At the last minute, a few test models fortunately became available. Their very limited mileage had, so far, only registered minor faults ... and so it was the Triumph Tina was announced, seemingly brilliant in its original conceptual design but, as time would very shortly tell, leaving much to be desired in proven engineering.

Tina scooters began to flow from the new production line in March 1962, and serious faults became evident almost immediately ... frames were bending and engines proving impossible to start, but by far the most serious concern was a problem that caused the automatic transmission to lock solid. The difficulty with this particular failure was that the Tina had no normal neutral gear and, without any warning, when the CVT jammed, it completely prevented the scooter from being wheeled about, and required the bike to be bodily lifted from the highway for attention. Within mere months of introduction, the new Tina scooter had become a laughing stock!

The problem with the CVT lay in trying to use steel balls to centrifugally operate the driving pulley (Yes, Motobécane manage this OK with their Dimoby system, but this employs a separate ball cage with formed guide tracks to enable pressure release). Since the Tina automatic transmission system had mainly been tried on a free-running test rig, the almost complete lack of road testing had failed to pick up that the centrifugal bearings didn't actually roll up and down the flat inclines of the driving faces, and because of their limited contact, would create a pressure point under driving load - and jam up!

Since Turner had failed to appreciate this problem, it came down to Hopwood to resolve the issue by the idea of replacing the balls with sliding wedges.

Already, many Tinas were out in the market, more churning off the assembly lines every day, with further problems and complaints from unhappy dealers and customers pouring in. Resolving all the problems would involve redesign of almost every major item in the machines specification - the disaster had arrived!

Skipping onward to today ... and what have we got, but a Triumph Tina, built right in the middle of the ongoing fiasco, with serial LS11132, and registered 610 EWD in February 1963.

Quoting a few specifications for data reference: Engine horizontal-cylinder fan-cooled two-cycle, iron cylinder 50.4mm bore × 50mm stroke for 99.75cc with 7:1 compression ratio alloy head, giving 4.5bhp @ 5,000rpm. Carburetion is 11/16 inch Amal 32/1. 3.50 × 8 disc wheels with 5-inch brakes, seat height 26 inches, wheelbase 46 3/8 inches, length 63½ inches, fuel capacity 1½ gallons and, most importantly, weight 143 pounds (dry), that's over 10 stone - for when you're dragging it off the road with a seized transmission!

There's no ignition lock & key, just a small toggle switch below the anticlockwise 60mph Smiths speedometer mounted in the headset, of which, the Riding Instructions say "Start/Drive switch, move to left before starting engine and to right when you are ready to move off. (In 'Start' position, transmission cannot engage)".

Further to which, the Controls and instruments section of the handbook says "Safety Switch - When the safety switch is in the 'START' position, it prevents the engine speed from rising above tick-over even if the throttle is opened, and therefore prevents the scooter from moving forward accidentally".

OK, intriguing ... more on that later.

The footbrake pedal is a U-form section over the frame spine, so you can use either (or both feet) to operate the rear brake - which seems a smart idea. Try the front brake, and the lever feels quite heavy to operate. Despite having a new cable, it's easy to see why it's so clumsy when you look at the tortuous course around the front steering leg. The routing is correct, it's meant to be like that - but just a poor arrangement!

While we're down there, it's hard to miss noticing the trailing link front suspension comprises just a basic compression/rebound rubber buffer arrangement - Hmmm, simple but brutal. We're already bracing ourselves for that!

The petrol tank seems to form the base for the dual saddle, and the fuel filler neck exits through the back cover of the seat. There's a sort of dual operation petrol tap/choke control at left front of the body panel below the rider's seat, pull-on the centre plunger for fuel, and turn the wire loop on the outer sleeve clockwise for choke.

Because the dumb kick-start is on the left, most riders are probably going to kick the motor over with their right foot - so you're most likely going to be starting Tina off the bike. Now either on the stand, or off the stand, if you twist open the throttle and the engine starts, with automatic clutching and CVT, that may mean the bike could be off and away without you! The importance of that start/drive safety switch is probably now becoming appreciated, but where it could possibly fall over is that the obvious disaster could still happen if the operator isn't switched to 'start', since the motor might still fire up in the drive position.

Perhaps it might be better relabelled to put its criticality into perspective - how about the 'suicide switch'? Maybe instead of Start/Drive, labelled - Safe/Disaster?

The kick-start prominently announces its presence, a chrome lever with black rubber on a fixed head, sticking eternally out at 90° from beneath the left hand side panel, just waiting for opportunities to catch on objects as you're negotiating the bike in tight spaces or to crack your shin if you unguardedly brush past. Not only is it on the wrong side, but there's also something unnatural about a lever that kicks forward of the pivot. If a Tina owner has never used a normal right-hand kick-start that swings in a backward arc, then they may simply accept that's how it is, but to everyone else - it's just not right and will niggle forever.

The kick-start operating action is typically only half a job, since by the time the ratchet has loaded-up to turn the motor, the arm is already below 90° of arc, so you don't get a proper kick, only a pat - just typical scooter, they rarely seem to have decent kick-starts. The kick ratio is fairly high, presumably to compensate for the limited arc of travel, so the result is a rather 'heavy' feel for such a small 100cc engine, particularly when the engine was hot - little wonder they became difficult to start!

Letting off the lever after a kick, the open ratchet loudly rattles as it returns, leaving a somewhat primitive impression.

Tina doesn't have any neutral gear, and neither has it any 'automatic clutch' mechanism in the normal physical sense. The CVT drive belt idles within the cones at rest, and increasing revs centrifugally throws wedges to thrust the outer cone into engagement with the drive belt. The nature of this transmission means Tina feels quite heavy to wheel about, as if a brake is dragging, since you're going to be back-driving the transmission and reduction gear in the rear hub.

Appreciating you can't bump-start this automatic CVT arrangement; our expectations are startlingly defeated after just a couple of pats on the starter easily fire the engine. The idling motor quickly starts coughing, so we customarily ease off the choke and tweak at throttle to compensate. While the action still manages to clear its breathing, the revs are held on tick-over by the ignition interrupt in 'start', and it feels somewhat odd as twisting the throttle fails to achieve any rev response until the switch is changed to 'run'.

The silencer emits a deep thumping pulse on regular tick-over beat, not at all the tone we are now programmed to expect from modern scooters. Tina's note is much like the old Villiers engines of the period, and could easily be taken as a larger capacity from the sound.

Opening the throttle raises the motor to a muffled roar as the auto-transmission engages and power feeds in. Take-off is actually quite impressive as the low starting ratio smoothly graduates into high drive, while the engine delivers its torquey performance from surprisingly low revolutions considering the small 100cc capacity. There's really no comparison to the frantic acceleration of buzzy modern scooters; Tina's feel is worlds apart, with a constant torque urge and flat droning tone.

While admittedly impressed with the motor's delivery, the steering doesn't impart anywhere near the same confidence ... there's a sort of wandering wobbliness, particularly on corners, that constantly questions who might actually be in control.

Pile on the throttle and the motor smoothly delivers brisk acceleration to a nasal induction drone, up to comfortable cruising speed around 30mph. This useful torque means the scooter is still fairly practical to use in town traffic, keeping up with general town pace enough not to be holding up the usual frustrated motorists. As speed may fall away against an incline load, there's still enough throttle in reserve to feed on more power and the reactive variator raises the revs to maintain the pace, so hills are coped with quite confidently, and without the fade that period mopeds of half the capacity would typically suffer.

CVT operation maintains fairly constant revs throughout the acceleration phase, and they don't really start increasing on the flat until 30mph+, which is pretty much the point the gearing tops out. Period tests generally credited Tina up to 45mph performance, but in deference to the brand new/old stock motor that's literally just been put in our feature bike, we didn't exceed 35 on our run.

Tina demands some slight adjustment to your riding practice in the deceleration phase, since the CVT disengages drive as the revs drop, so you find yourself coasting into corners with no engine braking available. While there is no effective engine braking on overrun, Tina still isn't quite free-wheeling, since there's residual drag from back-driving the transmission system that noticeably reduces rolling speed as the power is backed off. Having small wheel physics working with the very adequate 5-inch drum brakes, there's plenty of stopping ability to compensate, so it's just a matter of slightly adapting your technique.

Lights operate from a Wipac switch on the headset; click clockwise for main generator lighting (battery-less AC system), centre position off, and click anticlockwise for the dry cell battery parking set. This was a period requirement for on-road parking at night in the 'good old days', which created jobsworth employment for idle Bobbies in the evening, putting unlit parking tickets on vehicles where the batteries had gone flat.

Long time deleted from the statute as any legal requirement, none of the systems ever work any more, you can no longer buy the original batteries, and despite dismantling the entire Tina, we couldn't identify where the battery even mounted - the owners manual illustrates the type 800 3-Volt battery in the wiring diagram, but nowhere tells you where it's supposed to be!

Anticlockwise speedometers never seem right, they somehow feel as if you're going backwards, and it may not be quite natural to recognise the 30mph marker coming up on the right of the dial. The Smiths 60, fortunately indicates 30mph at 12 o'clock, so sort of manages to get away with it, but doesn't mean that everyone's going to like it. Probably as expected from quality equipment, readings from the Smith's instrumentation matched those of our pace bike, a considerable improvement over the often wavering and inaccurate speedo sets experienced on many of the mopeds we typically run.

The front suspension did everything we expected - it beat us up! The rubber buffer trailing-link is most unsuitable for handling any rough stuff, and hitting a pothole would certainly see most of such impact transmitted to the machine. It could be easy to perceive much of the front suspension performance being attributed to some of the frame bending reports.

By comparison, the hydraulically damped, single-sided spring suspension worked much better at the rear, so no adverse reports from the tail end.

After our run, stopping Tina on the handlebar cut-out button doesn't seem to work - until you flick the 'safety switch' back to 'start' position to enable its earth. This was probably an intentional feature to return the switch from 'run', and ready for re-starting again in the correct position.

Riding astern of Tina, you tend to observe there's more rear body panel on the left than the right, so the bike is visually unbalanced from behind. This is because the CVT mechanism protrudes more on the drive side, and the bulbous removable panel form extends further to cover the working parts on that side - just one of those things that might bug you!

Removing the left hand panel allows service access to the carburettor, CVT and drive belt. Ahead of this, the front left 'vent' removes by a couple of screws to gain access to the spark plug. Anything beyond these items requiring attention (including contact points), would pretty much demand removal of the rear body shell, and was unlikely to be a task performed by the roadside.

Unusually for a scooter, there is notably no toolbox or storage capacity anywhere on the vehicle. Considering that removal of the 'vent' and side panel service covers require a screwdriver, access to just such basic attention equipment (plug spanner/plug/carburettor) means this would have to be carried by the rider at all times - seemingly a bit of a design oversight.

There was a number of experimental spin-offs resulting from the Tina project, including a four-wheeled, two-seater vehicle affectionately called 'double trouble' by the development department, and made by bolting two scooters together with metal cross members. The steering functioned by a simple linkage bar connecting the right side to the left side headset.

Another non-production creation was the George Wallis three-wheeler Tina Truckster with tilting body, of which some twelve prototype models were built from 1967 as a concept development toward the notorious BSA Ariel 3 of July 1970. The Ariel 3 also employed Tina's same design of trailing-link, rubber compression/rebound, boneshaker front suspension.

The BSA Sunbeam B2 & B2S (electric start), and Triumph Tigress TW2 & TW2S (electric start) 250cc four-stroke twin models all discontinued production in 1964 and weren't replaced by any successor models.

The BSA Sunbeam B1 175cc two-stroke single discontinued production in 1965, and was also withdrawn with no successor, leaving just the 100cc Triumph to carry on the standard as the BSA/Triumph Group's only production scooter.

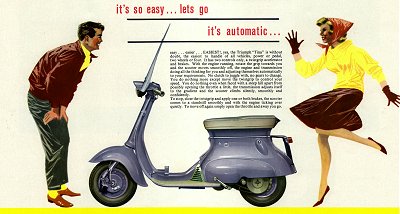

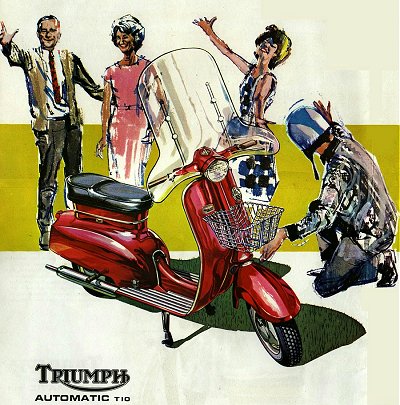

Brochure illustration of the Triumph Tina

The original Triumph Tina officially discontinued production in June 1965 after around 20,500 machines had been built, but the scooter carried on as a remodelled version "Automatic T10", which incorporated all modifications to resolve the initial problems, and restyling of the rear body section. The designation change to T10 was probably as much to try and divorce the now 'corrected' scooter, as much as possible, from continued association with Tina's stigma.

The redesign resulting in the T10 involved a considerable list of changes. The start/drive 'safety switch' on the headset was changed to a pressure switch under the seat that enabled operation when the rider was seated. This was possibly some indication as to how many people might have absently started the bike in the 'run' position, then blipped the throttle, to find Tina would fly off and crash on the floor.

Brochure illustration of the Triumph T10

The iron barrel and alloy cylinder head were recast with new fin patterns, while the Wipac magneto was changed to internal low tension coil with external high tension to resolve starting issues associated with the original internal HT magneto.

The rear body assembly was remodelled to a one-piece shell that hinged up from the rear, improving ready access to the motor, and including the rear lamp/number plate mounting on the body shell. The fuel filler neck disappeared from the back of the saddle. Instead, the seat folded up with a filler cap beneath, and now included a small tool storage compartment located within the top of the petrol tank pressing.

New artwork for the T10 sales leaflet also made more of promoting accessories, illustrating a machine with fitted windscreen, forward mounted 'shopping basket', bag hook, handlebar mirror, and pannier bag.

Tina frame numeration can appear a little mysterious...

Serialisation officially commenced at LS101, which was a bike initially held back for reference/development purposes, and finally disposed of by the factory, to someone in Coventry in October 1963.

While the registration document on our feature bike records matching frame and engine numbers as LS11132, things may not be so simple.

Engine serialisation certainly prefixes with LS or LS/S. Tina frame numbers are supposed to be marked on the frame near the carburettor, though not infrequently they appear to be unstamped, so frame numbers may often be recorded as the engine serial.

Whether this may have been because they simply were not stamped at the factory, or whether these could represent bikes that received replacement frames (from the 'frame bending' problem) isn't really known.

T10 numeration seemed to restart a fresh digit series with a 'T' prefix, of which UK market frames are generally reported having four-digit serials, and US market frames with five-digit serials, though this may possibly be just incidentally represented in US exports only starting after serial 9999. The T10 factory records seem somewhat muddled with anomalies, so rather complicate resolution of exactly how many were built. The 'vaguely official' figure of around 6,000 T10's produced appears appreciably short of the five-figure frame serials that owners can report, and an unlikely low number considering five production years.

T10 engine numbers seem to have continued the LS prefix series.

Another note suggests that some duo-tone painted versions may be indicated with a 'D' above the frame number.

Few people probably appreciate that the Tina and T10 continued the little Triumph scooter in production for eight years, though its reputation remained in tatters following the Tina fiasco. Following poor market sales, the T10 was finally discontinued in June 1970. Nobody probably even noticed it go.

Though Triumph's small capacity scooter wasn't the first such machine with automatic clutching and CVT drive, the concept and design represented a significant step towards development of what is so extensively built across the globe today. Looking at the general arrangement of almost any standard-formula modern scooter, it may be possible to catch a glimpse of Tina's ghost in its distant evolution...

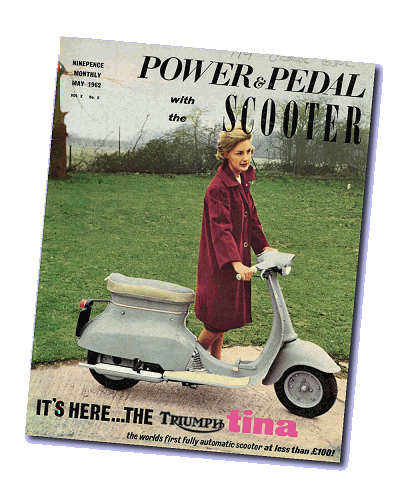

Tina on the cover of Power &

Pedal

Next - As World War Two ended, the second half of the '40s decade was to renew interest in motor cycling again, as a practical means of economic transport. In such times of austerity, the most economic means of transport seem to attract even more appeal, and new continental cyclemotor engines for attachment to bicycles would appear to offer greater frugality than old generation autocycles - and some unlikely British manufacturers may see an enterprising opportunity...

So where to mount the engine? It's interesting that our more successful cyclemotors of later years were all arranged appreciably differently than our pioneering cyclemotors started ... so why not Front Wheel Drive!

[Text and photos © 2011 M Daniels. Period documents from IceniCAM Information Service.]

How the Change of Tack Tina feature came about is surely as much of a saga as the article itself!

It all began, as many stories probably do these days, when David Campbell bought the scooter on a well-known auction website and dropped the bike into Felixstowe Motorcycle and Auto Centre to "Just get it going, and MoT".

Well, the bike appeared reasonably tidy but proved particularly reluctant to the usual encouragement to start and it doesn't take long for trade professionals like Sid Flavin to realise that things were seriously not well with Tina, and the difficulty and expense of sorting her out would neither be in his, nor the customer's interest.

Fortunately (or unfortunately, depending on how you look on these things), we'd spotted Tina in the workshop and obviously fancied the opportunity to get the little scooter for an article ... so following a chat with its owner, IceniCAM workshops ended up with another 'fix for feature'.

Further investigation into Tina's mechanical and electrical state revealed a seemingly unending catalogue of disaster: engine wrecked, broken transmission, carburation wrong and threads stripped, no wiring connected, wobbly wheels, the list was just endless - how much pain can you take?

Beneath a stall at Founder's Day,

between some pannier frames and a Dandy wheel,

it's a new T10 engine.

It was quickly apparent that Tina had received a 'cosmetic restoration', presumably as a static display exhibit, with virtually no prospect of ever working again, since practically every functional aspect was completely junk!

Why do people do this? If the bike's dead, you might as well just look at a picture!

Spotting a new T10 engine in a box at the VMCC Founders Day jumble in July 2010 seemed to offer some prospect of hope, and following a quick mobile call, salvation was secured.

Our engineering shops resolved the transmission reconstruction, rewired the electrics ... but the seemingly buckled wheels were rather a concern that should fail an MoT ... until we took the split hubs apart! Never before have we seen a bike that would fail an MoT for paint, but someone had sprayed the wheel halves with some 2½mm of bodystopper! Not only would the tyres not locate into the now 5mm oversize hub diameter, but the halves had been hung up during the spray process and the paint stopper had sagged to form 5mm thick runs at the bottoms of the clamping faces. When fixed together, and bolted to the brake drums, the rims wobbled like the wonky wheels of a circus clown's car ... but burn off the offending paint, a light re-spray to the hubs, they assembled fine and ran true again.

Unbelievable, but the whole bike was like that, completely and utterly numpty'd! An AC electrical set, fitted with a DC Honda horn - that was stuck together with mastic! The headlamp rim was bonded round by mastic (with no bulb in the lamp!), and why? Because the paint was so thick that the rim couldn't locate on the shell!

The petrol cap wouldn't even fit in the tank - because there was too much paint in the filler neck!

Just everything, and after months of reconstruction, we get it going, to find you still can't ride because it feels like a brake jams on every time you sit on the bike? The front suspension pivot bushes and bearing pin were so slack, that the wheel slewed over and the front tyre rubbed on the steering leg!

Finally, finally, a glimmer of light at the end of the long, dark tunnel...

All credit to the commitment of the owner, who stuck with the finance to see the project out, and finished up with a pretty decent bike in the end. A working Tina is certainly a fairly rare thing these days - there sure are lots of broken ones and, having experienced all the problems first hand, it's easy to see why!

Away from the workshop challenge, developing the text had nothing to start from, since we couldn't find any Tina material that anyone had done previously - so all the research and collation was initiated by IceniCAM. James Bradshaw at the triumphtina.com website deserves credit for being very persistent and helpful in assisting research towards the production of the article. The Triumph Owners Club was also good in coming up with more original material.

We'd like to say that enquiries to VMCC headquarters also resulted in assistance, but frankly, they were utterly useless. It's disappointing how such a leading motor cycling organisation can be so poor in its efforts - nil points!

Once research and work on drafting the text got underway, the article project was attracting keen interest from other publications as the prospect was very obviously becoming a reality.

Franchise versions of the Tina article are being licensed to the Vintage Motor Scooter Club magazine, Triumph Owners Club magazine Nacelle, and triumphtina.com website

Directly attributable costs to actually produce the article were practically nothing, but if we were counting vehicle reconstruction cost and workshop time, then Tina would probably equate on terms with a NASA space mission. As it was, Harold Wright of Suffolk Section EACC ended up collecting sponsorship credit on this key article, for just a single figure donation - just the way these things come out of the hat!

All the pain seems to pretty much fade into insignificance once the article finally goes out, replaced by some sense of achievement at the production and publication of another reference piece that nobody else seems to have managed before. Our contribution, another drip in the motor cycling pool of knowledge.