To many people, the Garelli brand will be synonymous with mopeds, but it hasn't always been so, and our story begins long before the moped ...

Adalberto Garelli was born at Turin in 1886, qualified his degree in engineering in 1908, and took occupation at Fiat in development and study of the first two-stroke engines. His employer however failed to reflect this interest in two-cycle motors and, after that brief chapter, they parted company in 1911.

The following year, Garelli set about developing his idea of a two-stroke split-single for more efficient scavenging, consisting of two parallel cylinders cast in a single block. Both pistons of 175cc were connected by a long gudgeon pin to a single conrod, for a total capacity of 350cc.

On 10 January 1914, Adalberto chose to demonstrate his design, by becoming the first person to climb the Moncenisio Pass on a motor cycle, and further accomplished this in treacherous and snowy conditions. Then, later in the year, he went on to join Bianchi as head of their motor cycle division. Another brief stop for the restless Adalberto found him moving on to Stucchi, a largely forgotten name today, but a prestigious motor cycle manufacturer of the early period. There, in a competition staged by the Italian Army, he won a prize for a military motor cycle version of his 350 split-single.

At the ending of the Great War in 1918, Adalberto left Stucchi to satisfy his dream and establish his own factory at Sesto San Giovanni near Milan, producing two further improved versions of his split-single concept, as the first Garelli motor cycle production commenced in 1919. A remarkable debut win in the Milan to Naples road race by Ettore Girardi elevated the new Garellis to instant public acclaim and fully occupied the works with demand for its 50mph 'Turismo' (Touring), and 75mph 'Raid' (Sports) models.

Racing Garelli 350s were soon campaigning on circuits across Europe, ridden by famous names of the day: Fergnani, Gnesa, Magnani, Nuvolari, Vailati, Varzi, and claiming no fewer than 76 world records between 1922 and 1926 by Fergnani, Visioli, then Gnesa, Maghetti and Shaitz.

Racing titles included the Circuit of Lario in 1921, International Grand Prix at Monza in 1922, the first Italian motor cycle victory abroad in a triumph on Strasbourg circuit, and Ernesto Gnesa securing first national racing Italian champion, all in the same year!

1926 however, was the last year the brand was involved in sport competition, with a 350cc model developing 20hp @ 4,500rpm and reaching speeds of 130km/h.

Following this, Garelli motor cycles for civilian sale gradually reduced as the company shifted towards equipment for military use to take it through the Great Depression years of the early 1930s.

By 1936, its involvement with two-wheelers had ceased to such a degree that the company failed to even gain an entry among the lists of Italian motor cycle producing factories.

Like many Italian manufacturers, Garelli emerged from World War Two with a devastated and ransacked factory and little prospect of resuming manufacture of its last military products for the former Fascist government.

Moto Garelli restructured shortly after the war, now calling itself SpA Meccanica Garelli and listing an address at Via Visconti di Modrone 19, Milano.

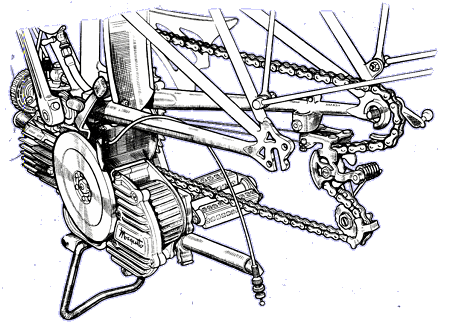

The tremendous demand for economic transport attracted a number of former military equipment manufacturers back towards lightweight motor cycles, but it wasn't until 1947 that Garelli returned to production with an innovative 38.5cc two-stroke auxiliary engine to equip common bicycles. The horizontal cylinder arrangement allowed easy attachment, and a friction roller transmitted drive direct to the rear tyre.

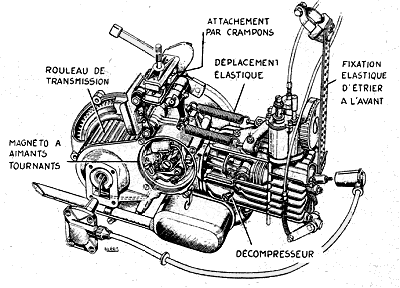

Unveiled at the Geneva Show in March 1947, from the house of Adalberto Garelli, with Carlo Alberto Gilardi as Chief Engineer to the project, the tiny type 307 clip-on motor was another instant success. Less than a mere 4 inches wide and weighing in at barely 4 kilogrammes, its 35 millimetre bore × 40 millimetre long-stroke specification of 5.5:1 compression ratio gave 0.8bhp @ 4,200rpm for 20mph, and the Dell'orto carburettor delivered around 200mpg economy!

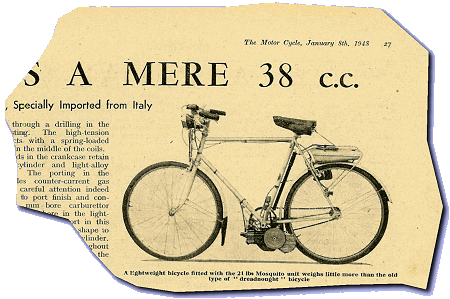

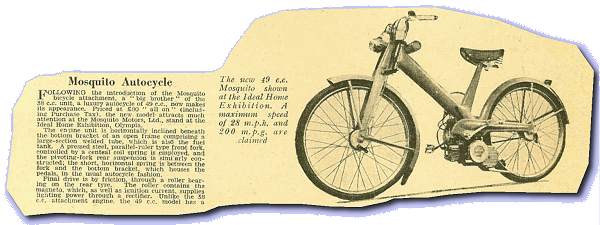

News of the Mosquito motor rippled across Europe, as journalists, impressed by the design and novelty of such a tiny motor, widely reported the engine in the motor cycling press. A small column in The Motor Cycle dated 8 January 1948 would seem to be among the first introductions to enthuse over Garelli's ingenuity to its British readership, while the Sterling Engineering Company of Dagenham entered speculative negotiations to try to make and sell Mosquito engines under licence onto the UK market, but their project was not secured.

Despite the lack of any national distributor, journalist Harry Louis still managed to acquire an example for appraisal and report in The Motor Cycle later in the year.

Unprecedented continental uptake of the engine, however, quickly found Garelli appreciating their position was failing to keep up with demand, particularly from France, where the Mosquito had become popularly adopted.

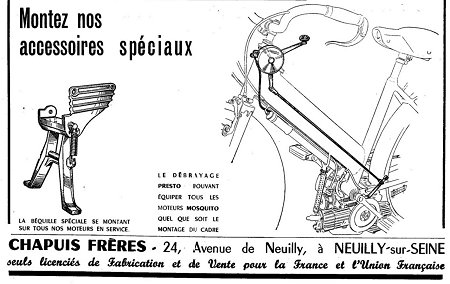

Solution to the supply problem came about by Garelli granting a manufacturing license to Etablissements Chapuis Frères, a long established maker of bicycles, at 24 Avenue de Neuilly, Neuilly-sur-Seine. To protect Garelli's name and reputation, the license came with demanding conditions requiring Chapuis lay out an entirely new factory to build the Mosquito engine, and expecting both high tooling standards, and machining facilities.

By 1950, Chapuis Frères had founded the plant, and selling not only their licence-built Mosquito engine attachment kits with Gurtner manufactured carburettors license-built to the original Dell'orto design, but also two complete cyclomoteur frame assemblies of their own construction, and sold under the "Presto" brand as 'Confort' and 'Sport' models.

Presto seemingly means nothing in the French language, but translates from Italian as 'fast', and we could now have an opportunity to see just how fast the Presto Sport may be, since we're most pleased to have secured one of these very machines for our Stingers feature.

There seem to be a number of alien controls on this cycle, so we twiddle with a few knobs and levers to see what's happening…

The twistgrip throttle appears fairly conventional, forward to decompress, and back for throttle.

By a system of operating rods, the inviting knob at the headstock moves the engine forwards and backwards to engage the drive roller with the rear tyre. The owner tells us the disengagement operation was originally accompanied by a secondary decompressor cable that would also cut the motor, but this function was disabled to allow the control to be used in a clutching function.

Inaccessibly tucked away at the bottom of the frame, behind the carburettor, it proves quite awkward to even get to the fuel tap, which is a dainty little brass lever affair. You'd probably never reach it wearing gloves, so getting petroily fingers is an inevitable consequence of Chapuis' thoughtless inconsideration for the rider.

A disc cover on the carburettor filter appears to rotate for

choke operation, we wonder what "Marche ![]() " and

"

" and

"![]() Depart" might be? After a little vague speculation,

we appreciate our command of the French language isn't up to

interpreting the meaning, so simply decide to try it in one

position, and if that doesn't work, then try it in the other.

Depart" might be? After a little vague speculation,

we appreciate our command of the French language isn't up to

interpreting the meaning, so simply decide to try it in one

position, and if that doesn't work, then try it in the other.

Just one look at the delicate cast alloy centre stand is replied by the answer "Don't even think about pedal starting this on the stand!"

There's a flood button on the float chamber, so we give that a little agitation just for good measure, then cycle away on the decompressor, throttle back and keep pedalling, and after a couple of encouraging phuts, the motor pops quietly away as we considerately assist it up and down the road to gently coax it into operation.

Finding that the carburettor disc cover can be rotated by left foot control, we turn it backward and forward to try to determine what may be choke and air positions, but are left none the wiser since choking seems to occur in the middle, while either other end appears much the same to the way the engine runs.

The handlebars are not a confidence-inspiring discovery, wobbly by design, since the bars are rubber mounted within the stem. Wondering if that may be for token suspension or vibration absorption, we really don't expect the feature to be contributing anything particularly useful, and would much prefer to feel a firm bar mounting instead.

The swept back form of the handlebars readily tangles with your knee at turns with inside pedal up, so we can already tell this will be a source of annoyance.

Easing down the road to the first junction, we edge down the throttle and lever the engine off drive to clutch the junction, then pedal away, latch back the engine engagement, and feed on the throttle. Well, though somewhat clumsy and ponderous, that clutching test worked pretty well, but only one brake could be effected during the operation, so it's probably not something you'd be wanting to execute in an emergency.

It doesn't take long to get the pattern of how the motor runs, four-stroking along at 20mph off-load on the flat, two-stroking along at 20mph on light-load inclines, or two-stroking along at 20mph into a light headwind. Efforts to improve our streamlining by tucking into a crouch make no difference at all, just the same 20mph - you may notice the common theme here being 20mph, and that's what it does!

On any steeper incline or against a stronger headwind, if the engine fades, you assist with a little pedalling.

Considering the 2:1 reduction drive, the motor doesn't sound to be overly working at this pace, and gives the impression it'd be quite happy buzzing along like that all day - however, at 20mph, the pilot of our pace bike was indicating signs of boredom...

The downhill run clocked up highest reading of 24mph, at which the engine felt most unhappy to be revving, and could be firmly taken as the absolute maximum.

With engine revs readily falling away on the following uphill section, pedal assistance was employed pretty much all the way up the climb to crest the rise.

Handling of the Presto Sport, with its rigid frame and rigid forks, could barely be assessed in any meaningful way at just 20mph. The knee fouling handlebars continued to annoy on cornering, the saddle was quite uncomfortable, but the bike generally rode well enough.

Operated by inverted levers that looked jolly quaint but proved typically cumbersome to operate, the front calliper and rear drum brakes weren't particularly good, but neither were they particularly challenged by the lowly cycle pace.

The cycle lighting set is powered by a friction driven dynamo running on the rear tyre, so basically cycle illumination for a cycle-performance machine.

Presto Sport however has a number of artistic touches that compliment its period appeal and contribute to its character: a cut-out section in the rear mudguard for the friction dynamo head, the spindly bar-form rear carrier neatly brazed to the frame instead of bolted on, the swirling cast alloy chain guard - so delicate… so, old French!

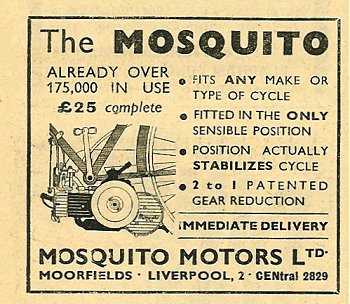

It was 1950 before Bob Sergent of Liverpool finally secured a sole UK licensing contract with Garelli, through his specifically registered 'Mosquito Motors Ltd', to import and market the attachment engine kit into Britain, from his established Moorfields motor and autocycle distributorship.

While this sales licence was initially established upon imported units, as early as April 1950, Sergent was making approaches to Crossley Motors Ltd of Stockport to manufacture Mosquito engines in Britain.

Crossley Mosquito engines were characterised by mounting a BEC (Bletchley Engineering Co) carburettor and engine numbers coded by CML letters, a batch prefix 1, and followed by a 3-digit engine number. An initial batch of around 1,000 Crossley units was completed before the year's end, but no further quantities were produced due to disagreements between the parties.

Sales continued with imported engine kits, and Crossley Motors closed in 1952.

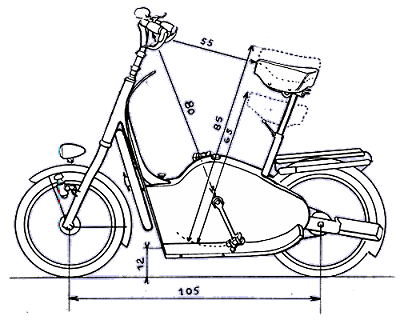

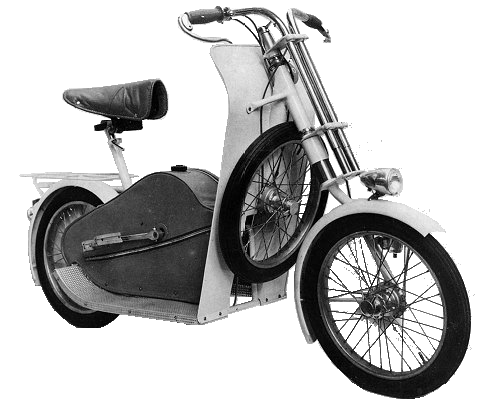

Le Salon de Paris exhibition in 1951 found the Chapuis stand displaying another new variant, this time posted as BMG: Bici Mosquito Garelli. This machine introduced a new 315 model Mosquito motor, with increased 40 millimetre bore × reduced 39 millimetre stroke now resulting in a 49cc undersquare specification for a higher 1bhp rating at the same revs.

With the bacon-slicer flywheel now enclosed within a cast aluminium engine cover, the changed visual appearance easily identifies the evolution motor, which was claimed to propel the machine around 28mph for 200mpg fuel consumption.

The large tubular-construction frame contained an integral fuel tank, mounted pressed steel blade girder forks up front, and coil-spring suspended, 'floating' swing-arm arrangement at the rear. From a typical rigid frame machine of the period, getting onto a BMG with no physical or visible means of support from the rear wheel must have been rather 'leap-of-faith' stuff for some riders of the time.

The cycle assembly, however, was constructed not by Garelli, but Industrie Meccanicha Meridonali, while the frame was fabricated by Metal Meccanica Meridionale, both companies being located in Pomigliano D'Arco.

Once again we are incredibly fortunate to be graced with another rare Mosquito 'light autocycle' (as these machines were generally described at the time) to support our Mosquito feature.

Presented with the prospect of another selection of potentially unfamiliar mechanisms, we check out the controls…

The right hand twist grip appears conventionally to open the throttle valve, while turning the left hand twist grip actuates the decompressor.

There's a lever petrol tap toward the lower right of the tube frame, but no obvious filler cap to mar the clean lines? Following the 'V' frame round to the seat stem, it looks as if there's something under the saddle ... and a knurled thimble, so we undo that, tilt the screw clamp from engagement, and hinge the seat forward to reveal a brass filler cap.

A lifting handle nestles in the crook of the frame, lift it at this point and the bike is in balance, so that's correct for operation. For those unfamiliar with what these frame handles are for, it's a typically continental feature for lifting cycles up steps, where many European town houses without gardens kept cycles in the hall of the house!

Toward the inside front of the left swing-arm pressing, sits a knob in a latch. Forward position engages the roller onto the rear tyre, while the rear slot disconnects the motor for cycling mode. Unlike the Presto, because of the location and required forceful operation, this engagement lever is certainly never going to be enabled in any clutching function, so generally the bike requires to be navigated on the decompressor when the engine is not running.

A disc cover on the Dell'orto carburettor filter appears to

rotate for choke operation, we wonder what "![]() Marcia" and "Avviam

Marcia" and "Avviam ![]() " might be?

" might be?

After a little vague speculation, we further appreciate our command of the Italian language isn't up to interpreting the meaning of this either, so decide again to try it in one position, and if that doesn't work, then try it in the other.

Another glance at the delicate cast alloy centre stand gives the same obvious answer as the Presto, "Don't even think about pedal starting this on the stand", but the legs appear longer, and comparison confirms this is indeed the case! The 315 has a 2 inches taller stand, and the motor has greater ground clearance but, correspondingly, the pedal crank is positioned higher on the frame, and places the non-adjustable saddle face just 20 inches from the axis.

Maybe this is the evidence scientists have been searching for years - cyclemotorists must have evolved shorter legs in the early 1950s! While there may be a few sceptics to scoff at this theory, the BMG is certainly awkward to pedal due to its short frame height. Seated cycling is most ungainly and quite inefficient, so we rather hope that the increased power of this larger motor type may not call so much for pedal assistance.

The same axis to saddle top distance on the Presto measured at 26 inches by comparison, much more 'correct' for cycling.

There's a flood button on the float chamber, so we give that a little agitation because it seemed to work with the Presto, then cycle away on the decompressor. The short frame height immediately tells, and demands adoption of a standing pedal position for delivery of enough power to turn the engine against compression, throttle back and keep pedalling, and after a couple of encouraging phuts, the motor burbles quietly into life as we considerately assist it up and down the road to gently coax it into operation - before setting off to administer another sound thrashing!

Once again rotating the carburettor disc cover by left foot control, we turn it backward and forward to try to determine what may be choke and air positions, but are left none the wiser since choking similarly seems to occur in the middle, while either end again appears much the same to the way the engine runs.

The exhaust tone adopts a nice crispy warble as the revs start to build, and almost feels like it might climb into a power band any moment, then take right off... Though the burst of revs doesn't actually happen on our Mosquito cyclemotor, you may catch a distant ancestral glimpse of where the howling Garelli 50s of later years originated.

On the flat, BMG readily adopted a natural cruising speed up to 24mph along the flat on about ¾ throttle, with the confident impression that it would run contentedly at this pace all day long.

Once the motor had worked a little more up to running temperature after a couple of miles, we opened up the throttle and tucked down for a best on flat pace of 25mph - the remaining ¼ throttle seemingly delivers little more effect.

The downhill run paced at maximum 32mph, while this engine capably handled the higher revs very much in its stride. Far more confident on this same element of the run than the smaller capacity Presto, which felt quite perturbed with the gravity-assisted extra speed. Probably the only significant difference this impression might be attributed to, could be the pistons, the BMG 50 piston being conventionally made from alloy, while the original 307 model 38.5cc piston was cast from iron.

Charging the following uphill climb on the BMG, the extra pace and increased power of the larger engine took us a little further up the other side before the revs faded away, and the inevitable pedal assistance was required to complete the rise. While offering a performance improvement on the smaller motor, a 1bhp engine would never be expected to ever manage such an ascent on its own.

BMG's brakes have to be worthy of comment. The cast alloy brake plates carry 'MG' (Mosquito Garelli) logos, and the makers name Metal Meccanica Meridionale - Napoli, but the drums appear so narrow that you have to marvel whether any shoes within are even three-dimensional!

The skinny brakes however, proved adequate enough over the test course, though we didn't really use them much, preferring instead to exploit the BMG's creditable corner handling to maintain a consistent pace through the bends.

Though supplied with a fitted lighting set, Mr Illumination was not at home! The BMG generator seemed to differ from the 307 cyclemotor set, in that the HT coil was relocated to an external mounting, and driven from a smaller low tension coil within the drive roller, to make room for an integral lighting coil.

Magset failure always proved to be the original Mosquito's weakness. Being so size-restricted by its location within the rear drive roller, and rotating at only half engine speed due to the 2:1 reduction drive, considerably disadvantaged the electrical capability. Combine these limitations within its adverse environmental location inside the rear drive roller, with all the associated grit and water being chucked about, and it's a sure formula for failure.

The Presto magset had obviously succumbed to this classic breakdown, with the ignition set resorting to 12 Volt battery supply, externally mounted capacitor and HT coil (within the basket).

Despite the improved BMG arrangement, its generator output still seemed to have deteriorated with age, now leaving insufficient spare power to drive the lighting set, which had to be sacrificed in order to maintain low tension output.

Mag generator problems commonly affect most Mosquito motors, and it's reportedly rare to find one still operating on its original contained system.

Motor cycling development was moving apace in these times, and the BMG Mosquito 315 model was only a brief machine. Production ceased at the end of 1952.

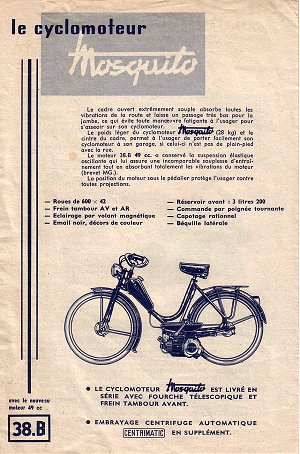

For 1953, Garelli announced yet another Mosquito engine, as the version 38-B cyclemotor.

This employed the preceding BMG engine, but omitted the internal reduction gear, so the drive roller located directly on the crank journal. Despite a compression ratio posted at just 5.5:1, the motor still quoted the same 1bhp, but re-rated at a lowly 2,800rpm - the buzzing Mosquito was now set to be droning along instead!

While further 'Centrimatic' versions of the 38-B now equipped engines with centrifugal clutching functions, one might have thought the old 307 series 'reduction' motor should probably have become obsolete by introduction of the 38-B direct-drive motors in 1953, but it didn't! The original 38.5cc motor remained in production, side by side with the later B-series models.

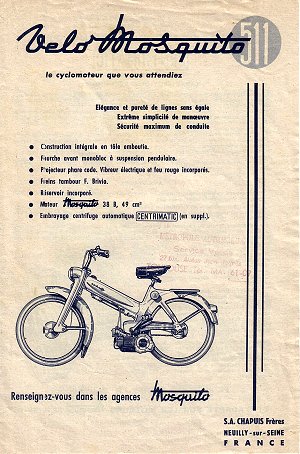

1954 found Garelli introducing the Velo-Mosquito, along developed lines of the earlier BMG. This purpose-made, pressed steel, rigid frame with leading-link forks was a simple and study mounting for the 38-B cyclemotor, and completed the missing link to the obvious next step.

As it would be recognised today, the first 'proper' Garelli moped appeared in 1955, but this was by no means any sudden end to the Mosquito cyclemotor series that had set Garelli buzzing on its way.

All three Mosquito cyclemotor engines, the Centrimatic 49 for £35-6s-6d, the 38-B direct drive 49 for £38-4s-6d, and even the original 307 at £30-9s-7d were still being listed available as late as 1960!

Over 20 years later, in 1983, remarkably, Garelli relaunched a new 36cc Mosquito cyclemotor auxiliary engine! The wheel of time seemed to turn full circle as the friction drive motor again became offered as the Bicimosquito attachment kit, or Velomosquito complete machine version.

The return of these economy models was not however any sign of further success, but an indication of the depressed state of business, and the desperate position in which Garelli now found itself.

The collapsed market for motor cycles and mopeds had led to an increasing dependence on activity from its Torpedo cycle division, and return of the Mosquito cyclemotor was perceived as a means to complement this now critical sector of income.

Next - We leave our Garelli lead feature for now, to rejoin the company again for a second chapter, from the late 1950s, and stumbling onward into the desert decade of the 1980s. The story doesn't however resume there, but starts a completely new thread back in 1900...

Adding to the confusion, and despite featuring three test machines in this next article, another crossover link connects this lead down a notch to support slot - so whatever's planned to takeover the lead feature must be something really mega, right?

[Text and photos © 2011 M Daniels. Period documents from IceniCAM Information Service.]

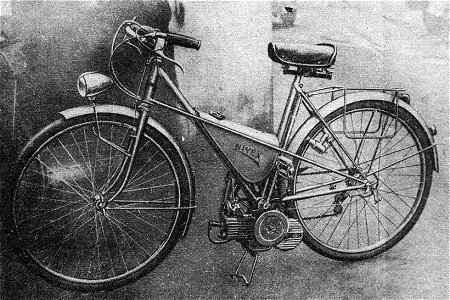

In France, although Chapuis Frères produced complete machines using the Mosquito engine, there were still many other makers of Mosquito-powered bikes. This example is the Nivex. While we were doing the research for Stingers, we turned up an article on this. the gear mechanism didn't look familiar, so that set us off on another tangent ... instead of doing what we were supposed to! Anyway, although not strictly relevant to our main story, we decided that, having found out about it, it would be woth tacking onto our Director's Cut.

Exhibited in 1950, the Nivex has a number of ingenious features. The frame is a variation of the mixte style that, by crossing over the top and down tubes, makes the frame extremely strong for its weight. It has a 3-speed dérailleur gear for pedalling and a clever quick-release mechanism for the rear wheel. The wheel can be removed without disturbing the pedal chain and, when replaced, the wheel returns into perfect alighnment with the frame, chain and engine drive roller without further adjustment. Nivex was a maker of cycleas and accessories and the dérailleur gear and quick-release were their own design and manufacture. As well as fitting them to their own pedal cycles, they also supplied these parts to other French builders of high quality cycles: Alex Singer, for example.

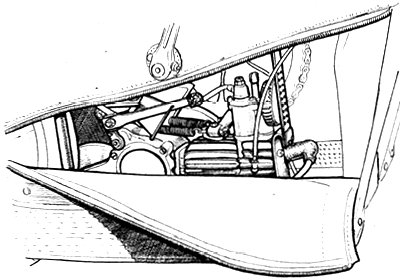

Yet another variation on this theme was the Scoto. This was a a cross between a scooter and a cyclemotor - and had a number of ingenious features. The Scoto had an aluminium frame with a single-tube spine; the bodywork that covered the engine, fuel tank and pedalling gear was of fabric on an aluminium frame. Peeling back the fabric revealed a 38cc Mosquito engine.

One of the big features of the Scoto was its wheels. Front and rear wheels were identical and their mountings were single-sided. If you had a puncture you just undid the retaining nut by hand, slid the wheel off, slid the spare wheel on, did up the nut amd away you went.

The first version of the Scoto wasn't Mosquito-powered; it had a Cicca cyclemotor engine: a roller drive unit above the front wheel. When the second version appeared, it looked a lot like the first version with the obvious exception of the engine and fuel tank being in a different position. What was less obvious at first glace was that the frame for the Mosquito was almost a mirror-image of the frame for the Cicca. This meant that the stub axles were now mounted on the left and the pedalling chain was also on the left. This in turn meant that the Scoto had to have a left-handed chain wheel, a left-handed freewheel and a left-handed dérailleur gear (The Scoto had two pedalling gears, one for starting, one for assisting). Because the chainwheel was on the left, the Mosquito's engagement lever had to be moved over to the right-hand side of the engine. In an article about the Scoto in Moto-Revue on 7 April 1951, "JH" wrote: "Nous pensons qu'il aurait été moins coûteux de le laisser à gauche, de mettre un plateau normal à droite, un roue-libre normal également sur la droite ainsi que le dérailleur..." Well, yes, it would have been less costly the other way round - but it wouldn't have worked. To maintain the simplicity of changing the rear wheel, it had to come off to the right, if it was the other way round, the Mosquito's transmission casing would obstruct wheel removal. If the wheel comes off to the right, the pedalling gear has to be on the left.

But it was costly, the price of a Scoto was 54,900 francs compared to 39,990 for a Presto with the same engine. Only 350 Scoto machines were produced.

Our Stingers production was probably unique in the way the article was developed, since the feature came about as a result of 'reverse engineering' from the title!

The BMG at Copdock Show

The initial idea may be said to have originated when Guy Bolton bought the BMG Mosquito at Copdock Show in October 2009, and we said, "We'd probably like to do an article on that sometime, when you've got it sorted out". While an age-related registration was secured though the East Anglian Cyclemotor Club, little more was seriously considered on the production front until early in 2010, when Mick Spacey turned up with the Presto Mosquito, which introduced the extra super-ingredient for a prime feature.

The Presto at Horham Show

Mick had the Presto up and running by the Horham event of May 2010, so development of a cyclemotor lead feature was finally on the cards - but the test schedule was really busy over this period, and there seemed no windows to see anything starting.

It was only on completion of Motom feature Out of the Extraordinary, mere days before the September edition 15 deadline at the end of August, that there we realised that we needed to commit to some sort of lead for Iceni edition 16. Should we continue the Italian sequence, or go for something else? Absolutely nothing was done on the Garelli article at all, but the Stingers title was dropped into the link. Call it optimism, call it rash, but now things really had to happen!

September is crazily busy with lots of events, a new Iceni Magazine in the middle of the month, then the build-up to Copdock Show on the first Sunday of October. There was no opportunity to start anything before all this was over, so with both the BMG and Presto planned to be on the EACC/IceniCAM stand at the show, it was decided to book the bikes into a road test on return from the event.

As Andrew flew off to New Zealand in the middle of October, back in the UK, Danny finally started work on the article, and Andrew returned three weeks later to a fairly well developed six-page draft, with completed road tests and photoshoots.

The road test element was by no means plain sailing. First attempt to run the BMG found the bike critically lacking in performance, and the tired old motor failed within 2 miles with no compression.

While the Presto behaved perfectly correctly for its performance, the BMG was whizzing through a lightning engine rebuild in the workshops, and returned a week later for a much more capable re-run.

The Stingers article had to be nailed down really quickly, since there were still two other features to complete for the next edition.

Costs were remarkably low for a main feature, since both bikes were delivered by their owners, and involved only £10 for fuel in just one return delivery for the Presto back to Norfolk.

Sponsorship for Stingers gets credited to Jeff Lacombe of the EACC Leicester Enthusiasts, so many thanks for his regular support of IceniCAM features.