Evolution of the moped in the years after the war was pretty much dominated by the two-stroke engine; excepting just a few, mostly Italian, four-stroke examples.

Though the somewhat oddball three-speed Motom from 1947 may arguably have been the best commercially produced machine, the Ducati Cucciolo popularised from 1946, would probably be more familiar to cyclemotorists in the UK, while other later 'specialist' 50s like the Demm Sport, Moto Morini Corsarino, MV Agusta Liberty, Nassetti Sery, Pegaso and Sterzi Pony seem to have largely disappeared into the obscurity of unused collections.

The singular all-British four-stroke moped was the quirky and difficult Mercury Mercette, only recording some 665 examples between its introduction at the Earls Court Show in November 1955, and the last recorded serial in October 1957, so was neither a commercially competitive nor a popular machine.

Shortly however, small capacity four-strokes from the Orient were poised to make a big impression...

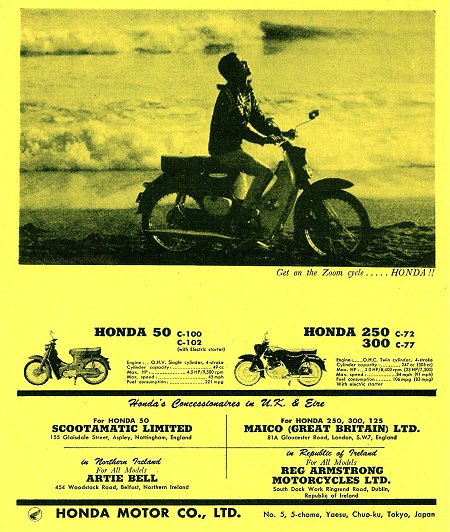

The first British public encounter with any Honda motor cycle occurred on the Scootamatic stand at the Earls Court Show in November 1960, when samples were displayed along with further selections from Auto-VAP, Capri, Como, Laverda, Velo-VAP, and Elswick-Hopper's Lynx prototypes. Formed by the management of Elswick Hopper, Scootamatic was a new company specially set up to handle sales of imported mopeds and scooters, though they actually declined the Honda, thinking it wouldn't sell.

Instead, listings were subsequently established through the Japanese company's own agency as Honda (UK) Ltd, Power Road, Chiswick, London W4, beginning with imports of just four listed models from November 1962: C100 Cub at £82-19s, C102 electric-start Cub at £101-17s, C110 Sport 50 at £109-19s, and CR110 production racer at a staggering £399.

While the CR110 was certainly an impressive miniature competition machine, it was the robust 50cc C100 step-through scooterette that proved the vehicle to pretty much establish Honda's public reputation for small 4 strokes wherever it appeared. This enduring little bike became their leading model in the UK after commencement of sales for the 1963 season, though with kick-start and semi-automatic foot-change motor, this machine actually classified as a motor cycle.

It was December 1966 before the first Japanese moped was introduced to Britain - the Honda P50.

The 42mm bore × 35.6mm four-stroke engine comprised a Cyclemaster-style motor wheel, with chain driven overhead camshaft, cast iron cylinder, and aluminium head delivering a relatively high 9:1 compression ratio, which might be perceived as a fairly sporty specification - but there were further aspects to consider…

'Breathing' was quite limited by tiny 15mm headed valves returned on weak single-coil springs, and secured by simple keyhole retainers - aspects not designed for power or revs, and operation that would inevitably become limited by valve bounce.

With the camshaft imaginatively hollow-cast from aluminium, the cams were only gently profiled and its rocker pads lubricated by a scrolled spindle via feed holes through the lobes.

While the exhaust valve operated in a guide, the inlet valve ran in the plain reamed aluminium (though a replaceable inlet guide was introduced on very late versions), and considering no bearing where the alloy camshaft runs directly in the alloy head - it becomes fairly obvious that lubrication maintenance was going to be particularly critical.

It's therefore further surprising to find there is no pressure feeding pump, but that oil dispersal relies upon an industrial practice 'splash flicker' fixed to the bottom of the con-rod.

All hidden within the hub, the single-speed transmission runs via a centrifugal clutch, through a sequence of three reduction chain and sprocket sets, to drive the rear wheel.

Standard fittings included a long arm wing mirror, steering column lock, electric horn, speedometer, front carrier, and tool kit.

Optional extras listed were a front carrier mounted wire basket fitting kit, a bracket for fixing an auxiliary front cycle lamp, an exhaust protector, legshields, windshield, front and rear pannier sets, and an indicator kit including rectifier and battery for charging from the flywheel magneto.

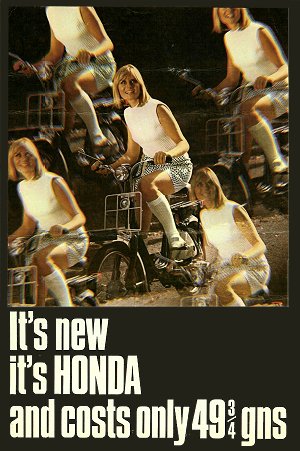

The P50 was presented at a pretty competitive selling price to attract customers, the period brochure saying "It's new, it's Honda, and costs only 49¾gns"… just £52-4s-9d!

By comparison, around this time an equivalent Raleigh RM8 model with front suspension and single-speed motor was being listed at £63-10s-9d, and the only mopeds appearing for less than £52 were the basic rigid-fork and calliper-brake Raleigh RM6 Runabout, the cheapest Mobylette, or Peugeot C model.

Our featured machine is one of the more common Japanese built small 17" wheel P50 models, of which 24,892 were imported into Britain, and available in colour options of scarlet, sky blue, or charcoal grey. A further 1,128 Belgian built larger 19" wheel P50 models were also sold into the UK, only available in grey.

Despite the different wheel diameters, the leading-link front fork and mudguard remained the same for both machines, and even carried onward to the later 1970s PC50 K1 model, which was laced with 19" rims. The larger wheel for the Belgian built P50s, would presumably gear up this model slightly, for potentially some +2mph (if the engine could pull the extra load).

With a rigid frame, the only suspension in the rear section is the springs under the foam saddle.

The fuel cap looks pretty scientific, having a lever on top, with what appears to be 90° rotation to lock 'on' or 'off'. Examination of the underside while turning the lever though, reveals this seems to have no obvious function at all, so we're left puzzled as to what that's actually about?

The air filter element is accessed under a frame cover logo on the left hand side, from which intake is drawn down through the vertical 9mm carburettor, unusual in that the float chamber is also vertically split, so very reliant on efficiency of its seal.

Not particularly convenient to access, due to being so low down and at the back of the bike, there is a drive switch at the rear of the motor, worked by a clumsy up and down latching motion. 'On' engages the motor, while 'Off' position just qualifies the pedal drive to allow for easier navigation when the motor isn't running.

For starting, fuel tap under the 2.5 litre tank on the left hand side, pull on the choke by a knob at the front of the frame behind the steering head. There is no ignition switch, so just thumb the decompressor (valve lift) under the left handlegrip; and either kick-start on the stand, walk beside, or pedal away, then let off the decomp and keep the motor turning till it fires up. In typical Honda fashion, it doesn't take much getting started, and you can edge off the choke quite readily.

Once running, the automatic clutch takes over, and since the drive clutch readily engages when the throttle is opened, pulling off from standstill really requires a little kindly pedal assistance from the rider, or the motor may labour painfully in this initial phase.

The engine's optimum and most comfortable cruising speed is found around 20-22mph, as without gloves, vibration at the handlebars quickly becomes intrusive for maintaining higher speeds. The engine and transmission also feels quite harsh running 25 and above, so generally deters continuing long in the upper range, other than for brief bursts.

On the outward leg of our test circuit, P50 pulled up to 24-25mph against a light headwind on the flat. Turning to a crosswind crept up to 26 still on the level. Filling the sails with a following wind saw a best of 28 along the flat, and fastest downhill paced at 32. Speed fell away on the following uphill climb, until the motor seemed to find its point of maximum torque and slogged up the other side at 20mph.

The speedo has no mileometer, and only reads to 30, though it appeared fairly accurate and gave comparable readings to the pace bike.

The brakes prove effective enough, but use of the front lever alone when signalling left is an unpleasant experience that riders would probably wish to avoid repeating, since the forks rear up on the leading-link suspension, while the wheel careers away.

A smooth ride is generally taken for granted from Honda, so it comes unexpectedly when this rigid frame delivers quite a battering along a bumpy road as the springing under the seat fails to absorb much of the motion, and the pilot becomes only too aware of the uneven surface.

The single filament 15W bulb of the 90mm Stanley headlamp produced a dull golden warmth at low speed, but managed to burn a little brighter as the revs got up, proving reasonably adequate for an economy moped of this age and such limited performance.

Today, replacement parts are no longer supported by the manufacturer, and present some difficulties to restoration. P50 wheel rebuilds may also be somewhat inconvenienced by standard 36 hole rim supplies, since the front rim requires 32 hole pierce, and rear 40 hole.

P50 production ran until April 1968, when it was succeeded by the PC50 installed with a similar derivative of the OHC engine.

Before the Honda PC50 K1 that most people generally know today, came - the Honda PC50. It's sort of the same, but different! The machine that everyone's probably most familiar with, is often the later K1, with its cast iron cylinder and head, and pushrod OHV motor. We covered this machine back in August 2003 in the article Turning Japanese, but the K1 was actually an evolution of an earlier PC50.

So why such interest in early Honda 'peds? It's not just the Classic Jap movement that's been growing for some time, but choices of old mopeds may also be influenced in modern times by emphasis on environmental awareness.

The old two-strokers may go on coughing along, but even among the old moped fraternity, some people just don't like to smoke!

Along our wayside of test features, there have noticeably been a few people that have independently raised the environmental issue, so it really is a consideration for some folks. One also has to wonder if it might have been a factor for some purchasers back in the 1960s, when they were out to buy their brand new moped?

Honda didn't noticeably seem to be raising promotional comment in any of their original period literature, so environmental issues generally seem to have developed sometime further on.

The main obvious difference to the later K1, is the installation of the chain drive overhead camshaft motor with its alloy cylinder head but, looking at the detail of the cycle parts, you can spot a number of specific differences. The petrol tank side pressing and toolbox moulding carry featured logo reliefs that don't appear on the K1; the exhaust is unique and not interchangeable to the OHV system; the back sprocket and rear hub are different; the headlamp is larger and moulded in plastic, rather than a steel pressing; and there is a small pressed aluminium logo trim to the bottom fork yoke that was omitted from the later model.

Registered in August 1969, our feature PC50 OHC is a particularly fine and genuine low mileage example that required little more than a cosmetic restoration and general service to restore it back to operation following a long period of disuse.

This model is also considered a 'Green Machine', particularly selected by its owner for its environmental, clean-burn, four-stroke qualities.

An easily functioned lever on the right engine cover switches the change from pedal mode to drive, though you do have to bend down to operate it. After drive mode is engaged the bike still allows free backward movement on the freewheel ratchet, but the engine turns over in forward motion and you need a thumb on the decompressor to allow navigation. Within easy reach, the fuel tap turns on at the tank outlet, but you have to bend forward to flip the choke lever on the carb, and you'll be back down there again shortly when you want to take it off. Starting is easy and there are three methods to chose from: kick-start style on the stand, walk alongside the bike and simply let out the decompressor, or pedal off down the road for a flying start (however this isn't generally favoured from cold since you'll have to bend down to take off the choke, and you may not want to be attempting that while you are moving).

Pull away from a stand-still is quite acceptable without the requirement of any boost on the pedals, the motor seemingly quite happy to handle this task on its own. Acceleration is also very reasonable, though the little engine may feel alarmingly revvy to people more used to traditional machinery. It doesn't take much to appreciate the drive ratio for these OHC machines is pitched on the low side, so you won't be expecting much top speed, and happy cruising is found around 25mph. While the engine pulls well into headwinds, it's surprising to find it fades more than expected when faced with an incline. The bouncy suspension rides the road surface smoothly, and the cycle frame both handles well and corners confidently. Highest speed recorded on the pace bike was 33mph downhill, with valve float occurring, so this really was the limit. Best on the flat with tailwind was 31mph.

Possibly not representative of all machines, both brakes were heavy to operate and weak in terms of performance. The front brake was too poor even to cause any concerning effects with the leading link fork rearing up, so that gives some indication how disappointing they were! The low, non-adjustable seat height would probably prove a less comfortable position for taller riders - maybe it wasn't originally designed with the European market in mind? The seat tips up to access the fuel filler for the tank on the left, and is matched by a plastic toolbox moulding on the right hand side, with lots of space for storage inside. A perforated metal carrier comes as standard equipment behind the seat. The lights are adequate for the bike's performance, though you probably wouldn't be feeling there was any illumination left in reserve, and use of the horn button produced an excited froggy croaking noise.

Imports of the original PC50 OHC officially ceased in April 1970, and were immediately succeeded by the K1 OHV model, which ran on till February 1977, after which Honda mopeds continued representation in two-stroke models only.

Changing environmental legislation and emission specifications in recent years have practically put paid to most applications of two-stroke engines in the western world, and now it's becoming increasingly difficult to even find new 50cc two-stroke powered scooters on sale at retail market outlets.

The wheel seems to have turned full circle, and the four-stroke engine appears to have won through in the end!

Next - Things might become a little confusing since a crossover link to the next edition finds the main feature and support feature switching connections. Our journey takes us back to 19th century Birmingham, where it often seems to be grey and raining - but not this time! It's a pleasant change when the weatherman predicts A little Sunshine.

[Text and photos © 2010 M Daniels. Period documents from IceniCAM Information Service.]

Green Machine was one of those articles that seemed to have been sitting in the can for quite a while, and there were probably times that a few of us began to wonder if it might ever get presented at all.

The article actually started as a single feature when we completed a road test and photoshoot on Surrey-based Mike Daborn's nicely restored PC50 OHC way back in May 2007. The initial idea was to put this out as a stand alone feature, but it never quite seemed to find a slot in the programme, so remained only as a file of rough draft notes.

Some time later as Alan Course in Cambridgeshire began progressing his P50 restoration towards completion, the idea occurred that the possibility of these two models together might make an interesting main feature due to the two models sharing a derivation of the same OHC motor.

Deciding this was the way to go, further development of the article was held over pending completion of the P50, however securing this bike for road test fell through for technical reasons, so the feature was packed away again in big box of mothballs, until such a time as another P50 might turn up.

Mike Daborn must have begun to wonder if his PC50 feature would ever appear!

Salvation finally came in early 2009, when Jim Stuttard from Lincolnshire acquired a smart P50 that didn't go, and it came through the workshops for sorting out. A deal was done, that when we got it running, we could have the bike for feature, and Jim would also sponsor the article, so with the second roadtest and photoshoot now secured, it was just a matter of working a main slot into the forward programme.

Its window was pencilled in following the Lido feature Back to the Future, until we actually got there, and the New Zealand epic World's End had leapt from nowhere, right to the head of the queue.

Because the research trip to the far side of the planet was such an ambitious project, with so many variables that could stop that article dead in its tracks, Green Machine was nominated as backup in case the Springer Gadabout feature mightn't work out.

World's End became largely written in draft along the way in NZ, and we knew that article was definitely going to run, even before the return flight touched down, back at Heathrow. With Green Machine again held over, the notes were sidelined yet again, till after edition 13 went out at the Radar Run on April 11th.

This left just two weeks before Danny & Dawn flew out to the Mediterranean, so a research pack was prepared, and from these notes, the text file drafted in Cyprus, to come back as a practically finished article on 5th May.

At the close of play, there added up a lot of work to present the final package. Though getting it to publication took such a long time, costs were pretty negligible, since both bikes were delivered and collected by their owners. Since the original PC50 photoshoot was so way back, this was shot in 35mm, so film, developing and digital conversion accounted some £7.50, but that was pretty much it!

There were times we all wondered if Green Machine may never get published, but as the Cypriots say, argá, argá - slowly, slowly!